Is acupuncture a viable alternative to opioids for patients in pain?

An acupuncturist inserts needles around a patient’s hip to relieve pain.

Gordon Liu, a 28-year-old office worker in Hong Kong, dashes to a Chinese medicine clinic after work to get acupuncture for his shoulder and neck pain. Liu goes inside a large cubicle curtained off for privacy. He takes off his shirt, lies face down on a bed and an acupuncturist puts needles in points near his shoulders, neck and hands, leaving them in for about 20 minutes.

“Now it feels like my neck and shoulders are more moveable, like they’ve loosened up,” he says.

Liu says it worked. Before the session, his neck was very stiff but now he feels better and is in less pain.

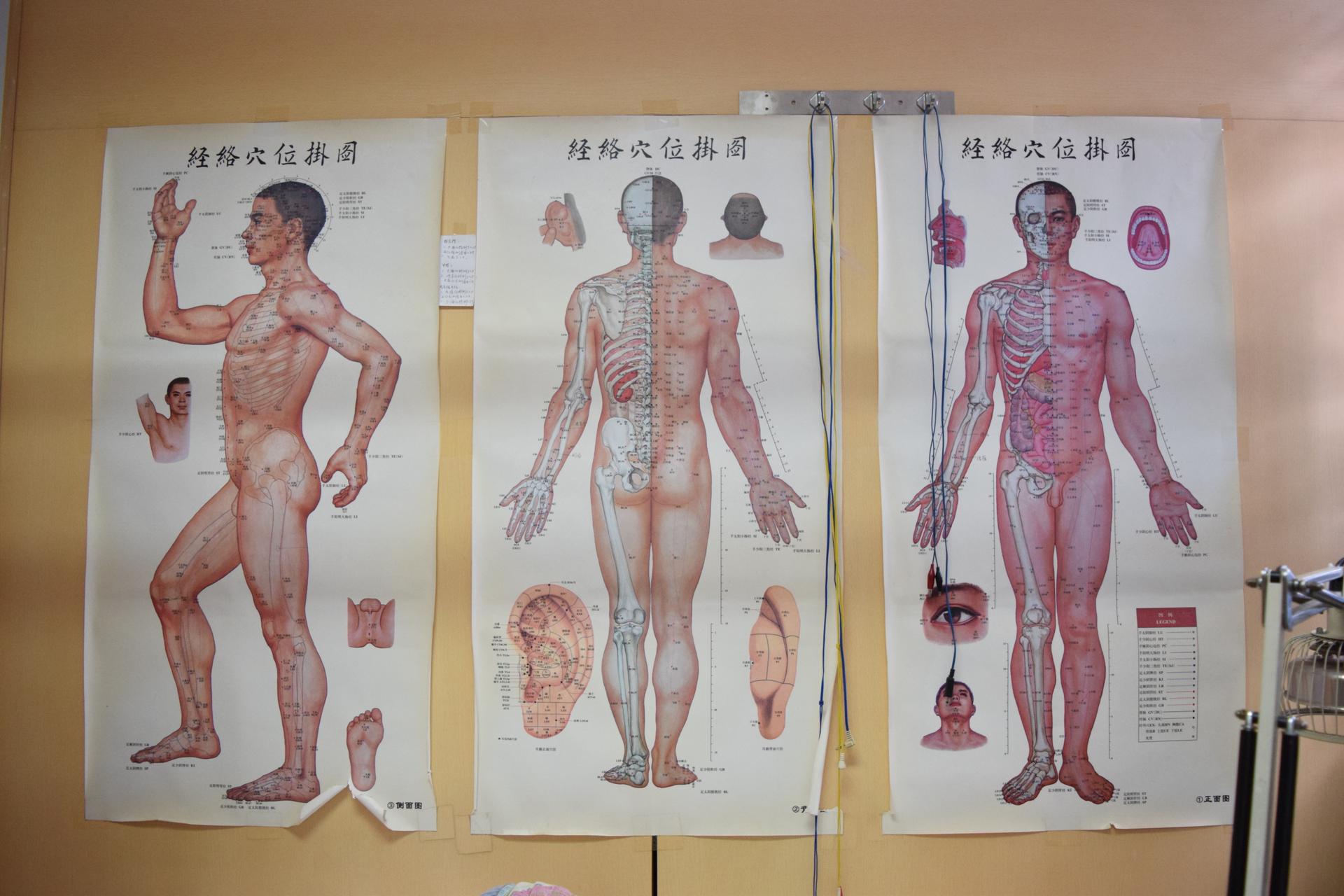

Acupuncture is the ancient Chinese practice of stimulating specific points on the body with needles. In Hong Kong there are more than 9,000 licensed Chinese medicine practitioners, most of whom practice acupuncture. In much of Asia, it is considered another alternative for pain treatment.

The clinic where Liu gets treatment is part of Pok Oi Hospital, one of the city’s public hospitals. His insurance covers the sessions.

Related: US health care companies begin exploring blockchain technologies

Chi-wai Cheung, an anesthesiologist at Queen Mary Hospital, one of Hong Kong’s largest public hospitals, says he recommends acupuncture to about 10 percent of his pain patients, but he would like to recommend it more.

“Some of the patients … we really cannot help them, with even … pain medication or interventional pain procedures,” Cheung says.

In Hong Kong, Western medicine is still standard but he says these are strong medications with major side effects, so acupuncture is a strong alternative, especially for his elderly patients.

“They cannot tolerate the pain medication, including the opioids,” he says. “The medication will cause them dizziness, sleepiness in the daytime.”

Inconclusive data

In the US a few health insurers cover acupuncture. But the ancient practice is not considered a medical option for pain control in healthcare circles. Critics say that despite many clinical trials, the results are still not conclusive. A recent review of clinical trials found that there was low to moderate evidence that acupuncture works for chronic neck and lower back pain.

Despite the inconclusive evidence, the practice is becoming more accepted in the US as a way to address pain. This is in part driven by increasing deaths from the opioid epidemic.

Related: In Vancouver, people who use drugs are supervising injections and reversing overdoses

Last year in the US, more than 49,000 died from fatal overdoses from opioids — a record high. The fatalities are often attributed to the overuse of prescription painkillers.

The Veterans Health Administration, as the largest integrated health care system in the country, is a major prescriber of opiate narcotics for pain. A 2013 investigation from the Center for Investigative Reporting found that opioid prescriptions to VA patients surged by 270 percent since the early 2000s and contributed to a rate of overdose deaths nearly double to that of the general population.

Related: As opioids land more women in prison, Ohio finds alternative treatments

The VA in Philadelphia has been offering acupuncture to treat pain since the 1990s. But with the recent increase in opioid overdose deaths, the agency has been making a push to offer more complementary and integrative health services, like acupuncture. Now, it no longer requires that acupuncturists also have a medical degree to practice.

Integrative health services at the VA

Reno Reali, 38, comes to the VA medical center in Philadelphia every two weeks to get acupuncture for pain in his neck and back. In 2005, when he was stationed in Iraq, he was badly injured in a mortar attack.

“There’s almost no disk left in my neck, like I had an 80-year-old spine when I got back from Iraq,” he says. “I had a herniated disc, I had disc degenerative disease, I had a lot of issues with my spine.”

Reali, who is tall with tattoos and a shaved head, went through several surgeries. He ended up in a wheelchair and in pain.

“I was in so much pain, like just getting out of bed took a lot of effort.”

For years, VA doctors prescribed Reali strong opiates, such as fentanyl patches, to manage his pain. But he says the medications made him foggy and weren’t that effective.

So a few months ago, he decided to try acupuncture.

“I was open to the idea because I just didn’t want to feel the pain anymore.”

‘The side effects are minimal to none’

Iliana Robinson is Reali’s acupuncturist. For most of the week, Robinson is a gynecologist at the University of Pennsylvania, but she also comes to the VA to offer veterans acupuncture.

“It’s the patients really who are wanting to decrease their opioids,” she says. “Acupuncture is one of the things that should be tried first. The side effects are minimal to none.”

Skeptics of the practice say there’s no science to support acupuncture and public resources should not be wasted on it.

Related: Thamkrabok Monastery has a reputation for its cold-turkey detox

“This is the thin end of the wedge where they’re [supporters of acupuncture] using placebo effects in order to continuously expand their claim and you are distracting people away from other strategies that might be effective,” says Steven Novella, senior editor of the blog Science-Based Medicine and an assistant professor of neurology at Yale University’s School of Medicine.

But as states grapple with high numbers of fatalities due to opioid overdoses, public health officials are looking for new ways to reduce prescriptions of opiate narcotics. Many states have done that by limiting prescriptions of painkillers. But more recently, a handful of states have started covering acupuncture treatment for pain through their Medicaid programs.

Medicaid to include acupuncture

“This is a leave-no-stone-unturned conversation,” says Barbara Sears, director of Ohio’s Medicaid.

Ohio has some of the highest overdose death rates in the country. Earlier this year, the state expanded Medicaid coverage to include acupuncture.

“We need to consider anything that we can that extends beyond just the opiate itself, so what other kinds of treatment forms are out there,” says Sears.

Related: A scientist who finds pharmaceutical promise in the venom of cone snails

California, Massachusetts, Oregon, New Jersey and Rhode Island currently cover acupuncture through their Medicaid programs. Delaware and Washington State are considering doing the same.

Vermont, which has been grappling with a high number of opioid deaths, also debated expanding Medicaid coverage to include acupuncture. But the state ultimately decided that more scientific research needed to be done before it could fund the ancient practice.

But for patients like Reali who has lived with pain since he was injured in Iraq, no scientific evidence is needed to prove that acupuncture works. He has been out of the military for eight years now and he’s finally getting his bachelor’s degree. He attributes much of his progress to acupuncture treatment controlling his pain.

“Being able to sit in a classroom without pain is great, to be able to walk without pain,” Reali says. “I was not able to do that with the medications.”

This reporting was supported by The International Center for Journalists as a part of their Bringing Home the World Fellowship.