The next cold war? US-China trade war risks something worse

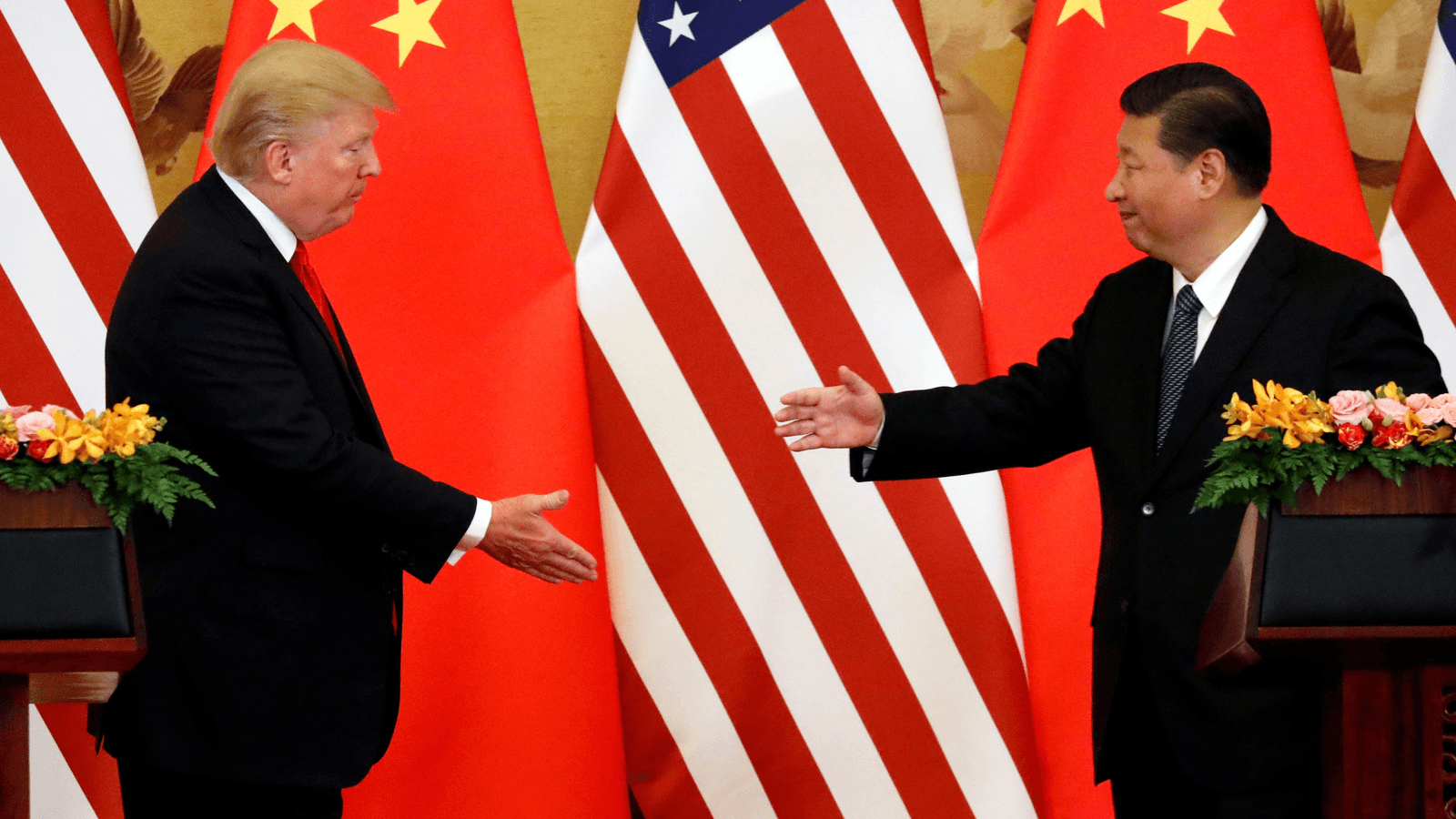

US President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping make joint statements at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, Nov. 9, 2017.

President Donald Trump is making good on his pledge to escalate the trade war with China by imposing tariffs on US$200 billion of Chinese goods. The Chinese government, for its part, is already retaliating with new taxes on $60 billion of American imports.

If you’re curious why China’s sanctions don’t match Trump’s, there’s an easy explanation. As a number of commentators have correctly pointed out, Beijing is running out of American products to target. Americans bought $375 billion more stuff from China than the Chinese bought from the US last year, which means Trump has a lot more to punish.

While this may mean that China’s leverage on trade is limited, it doesn’t mean that Trump can easily win this confrontation.

Related: China says US trying to force it to submit on trade as new tariffs kick in

That’s because China has many other ways to retaliate, such as dumping its considerable holdings of US debt or making it harder for Trump to get a nuclear deal with North Korea. In these and other areas, Beijing has enormous leverage. This has led some to suggest that the trade war may soon turn into a “new cold war.”

Could the US and China really be on the verge of the kind of geopolitical stalemate that dominated the second half of the 20th century?

Much will depend on how China responds to the latest tariffs. I believe that this response could take four forms.

Cooler heads

First, China could choose to de-escalate the confrontation. This could be done quickly by negotiating some resolution with the Trump administration – though the president’s terms for ending the trade war remain unclear.

Alternatively, China could let the conflict simmer by keeping the fight in the trade arena, allowing it to continue to retaliate while appearing “reasonable.” This approach would avoid any major embarrassment for China while kicking the dispute down the road in the hope that the November elections, or the 2020 presidential elections, will soften American policy. In fact, China has already said that it won’t negotiate until after the midterms.

A conciliatory strategy might be attractive to moderates in Beijing who are keenly aware that China needs the US as much as the US needs China. It would also reassure China’s other trading partners that it is serious about honoring its commitments.

Economic pain

Another option for China is to escalate the confrontation by using its substantial economic leverage outside of trade.

The most obvious way that China could retaliate would be by reducing its purchases of American Treasuries or by selling some of the $1.18 trillion in its possession. Overall, China owns almost a fifth of the US national debt currently held by foreign countries.

Though it would probably be less apocalyptic than is sometimes assumed, a Chinese policy of reducing its holdings would substantially drive up the cost of many of the goods that Americans buy every day.

The problem with this approach for China is that it would also strengthen the yuan and make Chinese goods more expensive for foreigners. Such a form of financial retaliation may not be a credible option for Beijing.

A more feasible strategy would be to target US companies operating in China with more regulations and interference. While such targeting would be contrary to international law, it would be fairly easy for Beijing to deny responsibility.

Indeed, there is reason to believe that China has used this approach before with South Korean corporations — and there are indications that it has already begun delaying license applications from American companies.

Geopolitical games

The US relationship with China is multifaceted, a fact that could allow China to retaliate outside the economic arena altogether.

One way would be to use its influence with North Korea to undermine US efforts to disarm Kim Jong-un, perhaps by not enforcing US sanctions.

Or China could confront the US in the South China Sea, probably the most dangerous strategic flashpoint in East Asia. As Beijing rushes to claim more islands and seaways south of its coast, a falling out with the United States over trade could encourage it to become even more belligerent.

Other options would be to ramp up its attempts to isolate Taiwan, deepen ties with Russia as a counterbalance to the US or accelerate its military buildup.

Hegemony on steroids

Finally, China could take America’s aggressive approach on trade as a reason to speed up its efforts to establish regional hegemony and greater economic independence.

The China 2025 program, a set of industrial policies aimed at moving the country closer to the technological frontier, could get a boost from the confrontation. China’s famous “Belt and Road Initiative,” an enormous economic corridor funded by Beijing, could be expanded, as could the country’s efforts to grow its influence in Africa. China could also pump more cash into its alternative to the World Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank.

Of course, China has sought to grow its influence, using all of the mechanisms discussed above, for some time. A more aggressive United States, however, could add to China’s sense of urgency.

What will China do?

The most likely Chinese response, in my judgment as a political economist, is some mixture of all four options.

Keeping the confrontation limited to trade — at least on the surface — is the safest bet for China’s leaders. And so I expect that Beijing will reserve its overt retaliation for tariffs. At the same time, I anticipate that China will engage in other noticeable but more informal and deniable actions against USeconomic and security interests — from causing headaches for American companies to building up its military.

In short, the Chinese government will seek to expand its powers so that it is able to deter future threats like these from the United States.

A different kind of cold war

In other words, President Trump is playing a risky game of whack-a-mole. In trying to tackle the trade deficit with a sledgehammer, he’s creating a host of other serious challenges to US interests that may persist for years to come.

The enormous and persistent US trade deficit with China needs a solution, but tariffs aren’t it. A wiser American approach would be to use the existing mechanisms of the international order to resolve its legitimate trade grievances with China.

And there are other ways to reduce the trade deficit and mitigate its ill effects, such as by encouraging higher savings rates, cutting the federal deficit (made worse by Trump’s tax cuts) and promoting competitiveness through job retraining and investment.

But back to our original question, are we heading for a new cold war?

In short, no, at least not the kind fought between the US and Soviet Union after World War II. The Cold War may have been frozen in Europe, but it led, directly or indirectly, to terrible conflicts in Korea, Vietnam and beyond. It also divided the world into two mutually antagonistic blocs constantly struggling for the upper hand.

Certainly, a growing conflict between the world’s two largest powers could again encourage the formation of opposing spheres of influence. But the economic interdependence between the US and China — as well as the existence of other major powers — would make such a “cold war” quite different, and probably milder, than the previous one.

Nevertheless, it is better for the US to avoid a confrontational relationship with China altogether. It’s natural to defend one’s interests, but an escalating fight, leading who knows where, would benefit no one.![]()

Charles Hankla is an associate professor of political science at Georgia State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!