Before coal disappears from Germany, more villages will

A cokery plant in Bottrop, the last of the hard-coal mines in Germany, will shut down in December.

Norbert Winzen is a 53-year-old nutrition expert. He is gentle and self-effacing and does not think of himself as an activist. Yet it’s a role that he finds himself in. Winzen has become the face of resistance in his village of Keyenberg, in western Germany — a region with a long history of coal mining and the heart of the country’s post-war industrial growth.

Like many of the surrounding villages that dot the area, Keyenberg is ancient and atmospheric, with ruins dating from the Roman era.

“Our village was named in the ninth century, 400 years before Berlin was founded,” says Winzen.

Related: America’s leading coal state looks to the wind

He lives with his family of nine in a handsome brick-walled farmhouse that was built in 1863. The family has lived in the village for generations.

“My father was a farmer, but he knew that the mine was coming closer and closer to us. He always told me, ‘Don’t become a farmer.’”

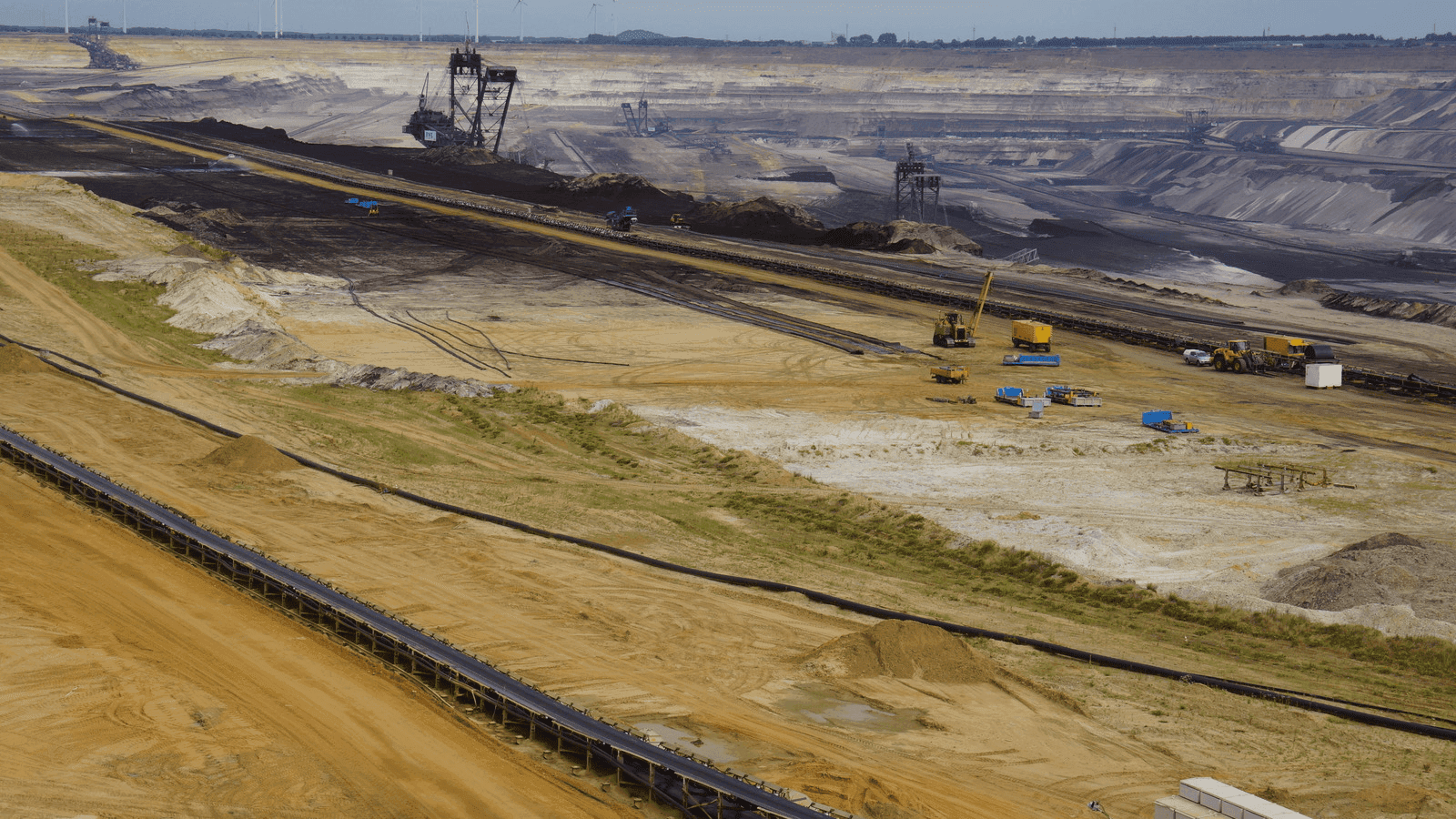

Keyenberg is located close to Garzweiler II, an open-pit lignite mine. For the last 30 years, village residents have been living in fear as the mine, owned by the German energy conglomerate RWE, has been steadily encroaching on their land.

The resettlement process began in 2016. After years of resistance, most of the 1,000 inhabitants have given up and have started building their houses in Keyenberg-neu, a new settlement for people living in the village.

Related: Britain built an empire out of coal. Now it’s giving it up. Why can’t the US?

Winzen feels the mining company shortchanges people under the guise of fair compensation. He was offered 3,000 square meters in return for his 8,000-square-meter parcel of land. But there is not much he can do. By 2023, Keyenberg will be entirely demolished. His mother, Käthe, who is 74, has lived here all her life and says she hopes to die before she has to give up her home and land.

Lignite mining has already claimed nearly 50 villages in the region, and since the mid-1950s more than 40,000 people have been displaced by it.

The earliest mention of lignite in the western Germany Rhenish region is from 58 AD. A report written by the Roman historian Tacitus details a fire that erupted from the ground, destroying crops, villages and “the wall of the newly established settlement of Cologne.” The relationship between humans and lignite has never been easy.

Germany is the largest lignite producer in the world. Lignite (brown or soft coal) is easier and cheaper to mine — it is extracted from the surface, not underground — and is more damaging to the environment than hard coal. It is the single most-polluting energy source. And lignite accounted for nearly 23 percent of Germany’s power production in 2017.

In spite of promises, Germany continues to rely on coal

This does not jibe with the country’s vaunted commitment to Energiewende (energy transition), the planned transition to a low-carbon, environmentally friendly energy supply. Germany has pledged to phase out nuclear power by 2022 and to reduce carbon emissions by up to 95 percent by 2050.

But the country has already missed its next deadline. In June, the German government conceded it will miss its 2020 target of reducing emissions by 40 percent from 1990 levels. A new target has been set for 2030.

Related: Tiny Wolfhagen, Germany leads the country’s green energy transition

“For now, it is crucial to shut down a large share of the oldest and most polluting power plants by 2020 to reduce the emission reduction target gap,” says Claudia Kemfert, an energy expert at DIW Berlin (the German Institute for Economic Research).

That seems unlikely, as lignite mining continues unabated. However, the days of hard-coal mining in Germany are coming to an end. The last two hard-coal mines in the country, in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, will close in December. Coal mined from this region drove Germany’s industrial revolution in the 19th century and led to Wirtschaftswunder, the economic miracle after World War II that is also called the Miracle on the Rhine.

Related: In Germany, miners and others prepare for a soft exit from hard coal

About a decade ago, the German government withdrew subsidies from hard-coal mining, which made extraction unprofitable. However, the closing of the last two hard-coal mines is little more than a symbolic victory for climate change. In 2017, hard coal imported from Russia, the United States, Australia, and Colombia accounted for 14 percent of Germany’s power production.

Taken together, in 2017 coal formed nearly 37 percent of Germany’s energy mix; renewables contributed 33 percent.

“German politics has the problem that it focused strategically on the roll-out of renewables and left out the painful challenge to phase-out high-carbon assets — power plants that are based on hard coal and lignite,” says Felix Matthes, research coordinator for energy and climate policy at Öko-Institut, a nonprofit environmental research institute.

Related: Germany talks a good game on climate, but it’s still stuck on coal

Meanwhile, there is growing public pressure to phase out coal. Most opinion polls show that the vast majority of the German population would like to see the end of coal soon. The mine at Hambach in Rhineland has been the site of an ever-growing movement that has attracted climate activists from around Germany and parts of Europe. The protesters, who gather by the thousands every year, demand an immediate end to lignite extraction in the biggest carbon-polluting region in Europe.

In July, the German government appointed a coal commission to set a final deadline to exit coal and to balance the conflicting claims of climate and jobs. According to data from May 2018, more than 20,000 people are employed in lignite mining.

“Lignite is one of the rare domestic non-renewable energy sources and the miners’ trade unions play a significant role in German politics,” says Matthes, who sits on the coal commission. “The challenges to the coal phase-out in a country like Germany are complex. It needs to be ambitious in terms of climate policies, but also designed in a way that it can serve as a blueprint for a managed and steady decline of an industry that plays a significant role in certain regions,” he adds.

Most experts agree that a disruptive coal exit would be good for the climate but would create major social disruptions. Reinhard Radloff, 67, is a retired mining engineer whose son works at RWE.

“Those who say ‘shut down the mines,’ I can understand their desire, but it’s unrealistic because all changes need time,” says Radloff. “But I also feel sorry for the people who have to relocate, and give up their villages, their churches, their history,” he adds.

New schools, shops and houses can always be built, but when a village disappears, so does a way of life. Hubert Perschke, a photographer, has documented the village of Manheim, near Keyenberg, in his book, “Mein Manheim.” He spent months taking pictures and talking to people about their memories before they moved to Manheim-neu.

“Most people living in Manheim had lived there for a long time. The street names or smaller monuments were taken along, but nevertheless in the new village the “old one” is no longer recognizable. The buildings are all built at the same time and do not convey a tradition. The previous neighbors live in different houses, but no longer next to each other. Old social structures are no longer valid in the new village,” says Perschke.

At Keyenberg, Norbert Winzen directs us to his favorite part of the village — the church — which dates back to the early middle ages. As a young boy, Winzen would visit the church with his grandmother. When he brings his daughter here, he leads her to the last bench, where he would always sit, and tells her stories of the people who were baptized and married, and all the special occasions that were celebrated in the church.

“Soon I will not be able to bring her here,” he says.