Cuba solidarity groups support the revolution from the US

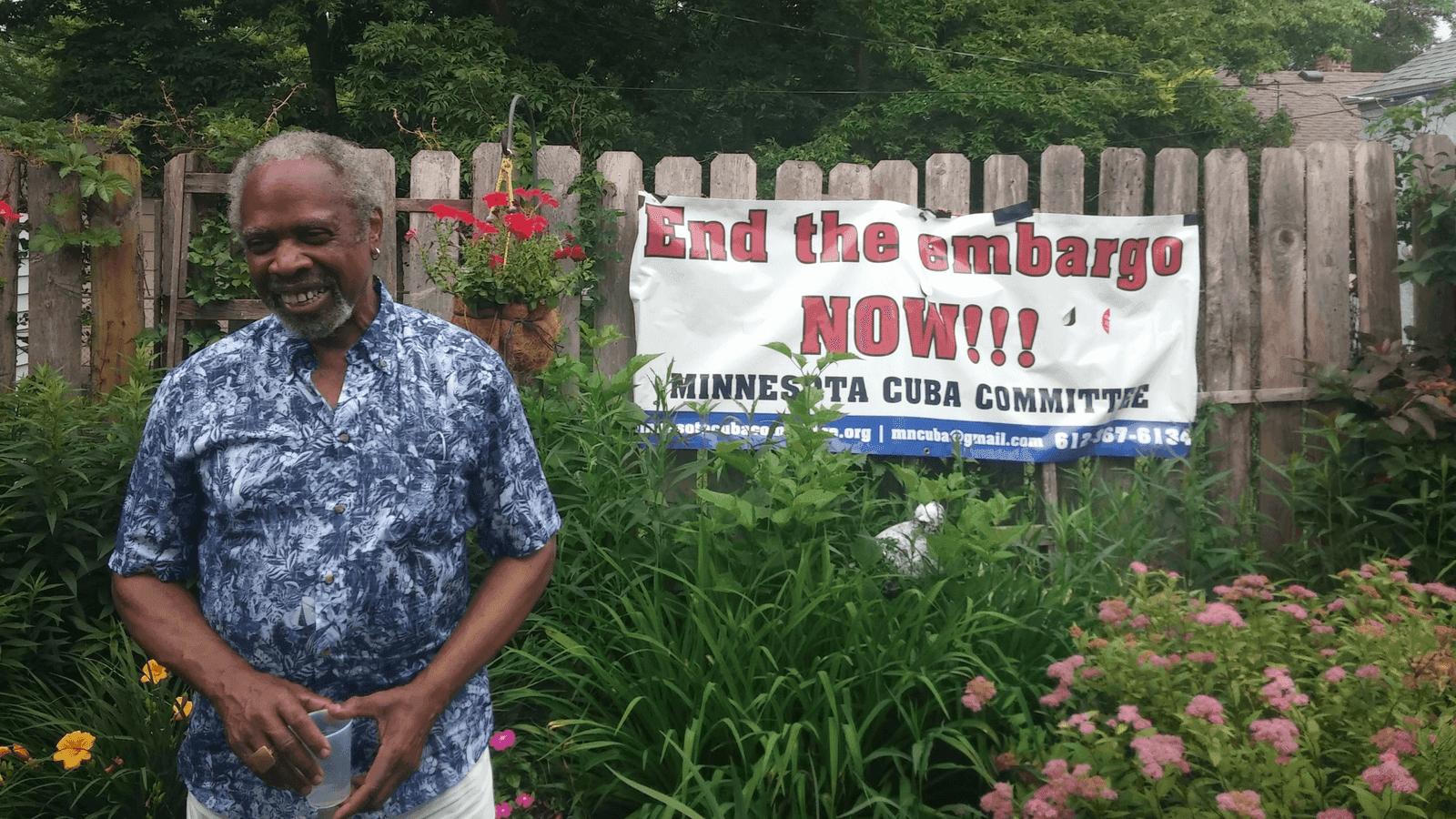

University of Minnesota political science professor August Nimtz co-founded the Minnesota Cuba Committee nearly 30 years ago to express support for Cuba during a time when other leftist governments around the world were collapsing.

In the backyard garden of a modest home on the east side of St. Paul, Minnesota, two dozen people drink mojitos and chat on a humid Sunday afternoon.

One woman dons a shirt emblazoned with Che Guevara’s image. Another man wears a shirt advertising Havana Club rum. A banner reading “End the Blockade Now” drapes the backyard fence. Below it, in smaller words, is the name of the activist group meeting here: the Minnesota Cuba Committee.

People move inside to the basement to watch a documentary about a medical school in Cuba that trains aspiring doctors from around the world free of charge. One of the speakers featured in the documentary, Gail Walker, traveled from New York to be here this afternoon as a stop along her Midwest route to raise money for a humanitarian caravan to Cuba later this year.

After the film ends, Walker, executive director of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization, speaks about how her group facilitated getting 170 people from across the country medical degrees through Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine. She explains how the Cuban government is training these medical students, most of them people of color from low-income areas, to be “revolutionary doctors” who will “return to communities across the US that are in dire need of a perspective of medicine that really puts people first.”

She then credits former Cuban President Fidel Castro, the leader of the revolution that turned the island Communist, for his vision in starting the medical school in the late 1990s. The medical school, according to advocates like Walker, is just one of many positive stories about the Cuban government that isn’t often told in the US. Instead, she said, we only hear the bad things.

“We’ve been indoctrinated in many ways with a very negative perspective about Cuba — everything from dictatorships to lack of freedoms to whatever the case may be,” Walker says. “Our intent is to have people go to Cuba and decide for themselves.”

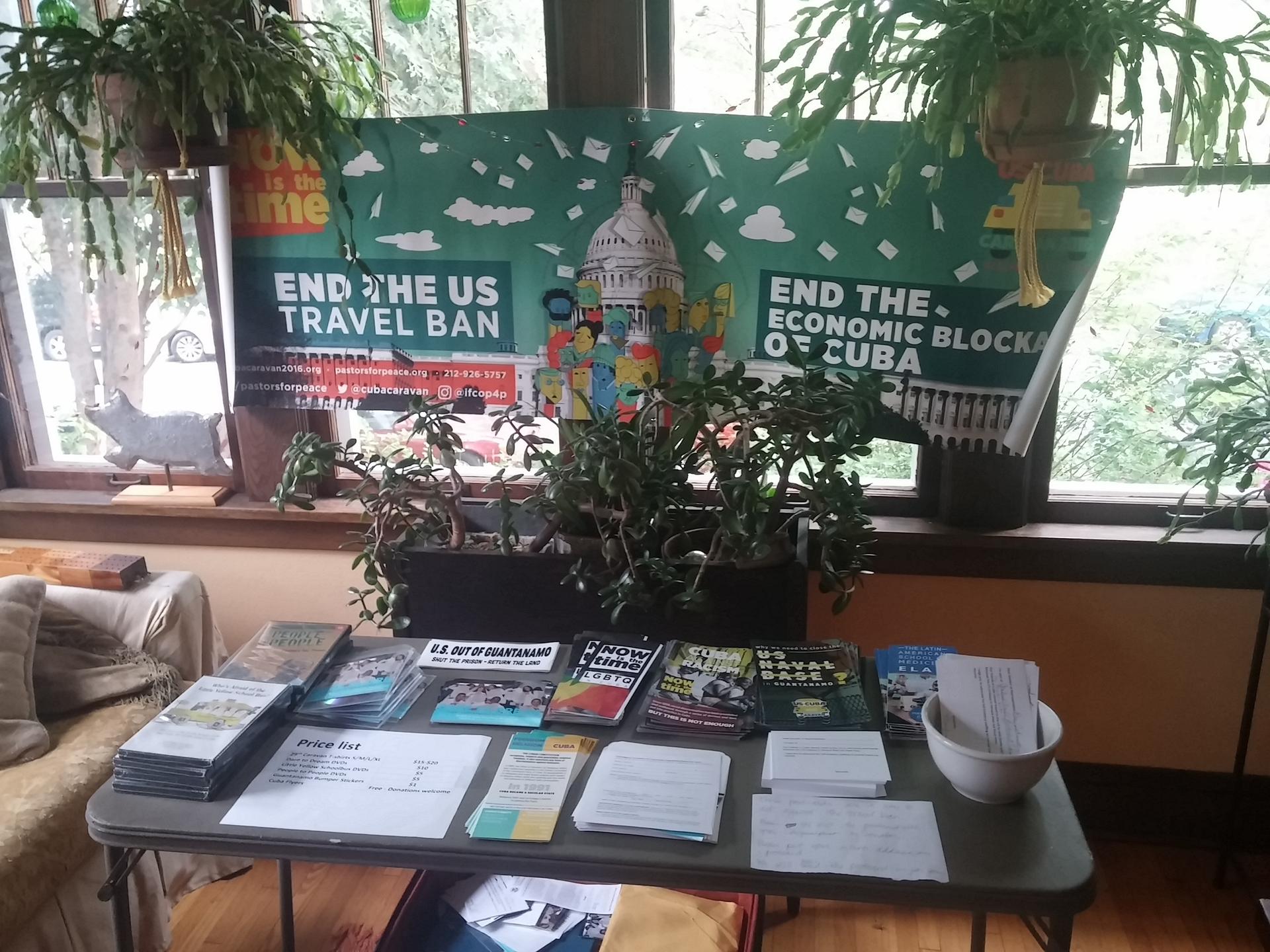

This goes beyond medicine. Each year, Pastors for Peace assembles volunteers for a caravan to bring goods — anything from medical supplies to regular household items like toasters — to the country in defiance of the longstanding US economic embargo against Cuba. The organizers bypass US-sanctioned travel to the island and instead get there through another country, like Canada. Walker calls this civil disobedience.

The Minnesota Cuba Committee is one of more than a dozen advocacy groups across the US dedicated to expressing support for the Caribbean island nation’s socialist form of government.

The group bases its advocacy on three main objectives: end the embargo, which the Cuban government and its sympathizers call the “blockade;” normalize relations between the US and Cuba; and educate the public about positive perspectives of the country not frequently seen in Western mainstream media.

Pro-Cuba groups across the US

Others groups like it exist in cities like Seattle, Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit and New York. They all belong to a national umbrella group — the National Network on Cuba — which hosts two annual conferences on Cuba solidarity matters, one in person and one on a conference call. This fall’s upcoming national conference will take place at Augsburg University in Minneapolis.

The groups work towards objectives in the legislative arena, too.

Members of the Minnesota committee, for example, have worked with the offices of two local politicians — Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat, and Rep. Tom Emmer, a Republican — on their respective bills currently before Congress to end the embargo. The Minnesota committee also backed a symbolic resolution to end the embargo that the Minneapolis City Council unanimously passed earlier this month. That effort made the pages of Granma, the official newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party.

St. Paul City Councilor Jane Prince, who briefly stopped by the Sunday house meeting and heard Walker speak, told PRI that she is currently looking into drafting a similar resolution for the elected body she serves on.

Greg Klave, a member of the Minnesota group, works on legislative matters like these. He credits traveling to Cuba in the mid-2000s and seeing the country’s lauded health care system up close with changing his life.

“We’re interested in showing that Cuba is not our enemy, they’re our friends and neighbors,” Klave says. “For us, solidarity, not division, is the way forward for world relations.”

Some Cuban solidarity activists, like University of Minnesota political science professor August Nimtz, are avowed revolutionary Marxists. Nimtz, who teaches a college course about the Cuban Revolution (which, full disclosure, I took in 2008), co-founded the Minnesota Cuba Committee nearly 30 years ago to express support for Cuba during a time when other leftist governments around the world were collapsing. The Sandinista-controlled government in Nicaragua had just lost elections and the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc were crumbling.

“Opponents of the Cuban Revolution were feeling emboldened, very confident,” Nimtz says. “They were literally dancing in the streets of Miami after the Sandinista defeat.”

Roughly 40 people attended the Minnesota group’s first meeting in April 1990 at the Zion Baptist Church in north Minneapolis. Among them was future Minneapolis Congressman and Democratic National Committee Deputy Chairman Keith Ellison, at the time a University of Minnesota law student and activist.

Currently, roughly a dozen regular members of the group meet every other week to update each other on the progress of their initiatives like the city council resolutions to end the embargo. The group also sponsors a yearly film festival that screens Cuban movies and helps interested people go on trips to the country through caravans like those sponsored by IFCO. They also get Cubans to speak at events whenever they can. Last spring, the group sponsored multiple events where a Havana University law professor on an academic fellowship at the University of Minnesota spoke about his role as an official observer in the country’s form of elections.

The modern solidarity groups are descendants of the Fair Play for Cuba committees that spawned in the early 1960s during the Civil Rights era and the beginning of a new wave of radicalism. Nimtz, a black teenager living in Jim Crow-era New Orleans when the Castro-led guerrillas ousted US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, says he was won over when he learned how the new government was “beginning to challenge the system of racial segregation in Cuba.” The Cuban government’s later military intervention efforts against apartheid regimes in Africa solidified his support.

“For those of us who came of age politically during the Cuban Revolution, it’s in our DNA,” he says.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons why so many members of the Cuba solidarity groups skew older.

“We’re an aging population and we haven’t attracted young people,” said Nalda Vigezzi, co-chair of the National Network on Cuba and a member of the July 26 Coalition, the Boston-based solidarity group named after the Castro-led guerrilla group. “That’s something that we could do better.”

Young activists lacking

Members are often at a loss to explain why young people aren’t attracted to Cuba solidarity work. Some, like Walker, speculate that the public is under a false impression that President Barack Obama already ended the embargo after he began normalizing relations with the country in 2014. President Trump halted the thaw when he took office.

Some US leftist organizations that include young people in their ranks are not on board with Cuba’s government. This includes Socialist Alternative, the Marxist political party that Seattle City Councilor Kshama Sawant belongs to, as well as the International Socialist Organization, which have both published critiques of Cuba’s government from a leftist viewpoint.

Of course, plenty of groups in the US criticize Cuba’s government from a more mainstream lens, most notably in the large expatriate community in and around Miami. Among them are the Washington, DC-based Center for a Free Cuba, which promotes “a peaceful transition to a Cuba that respects human rights and political and economic freedoms.” Frank Calzon, the group’s executive director, came from Cuba to the US as a teenager in 1960 shortly after Castro’s government took power. The solidarity groups in the US, Calzon argues, are simply repeating Cuban government propaganda when they call for an immediate end to the economic embargo.

“A lot of these groups are not Cubans,” Calzon says. “They’re for the most part Americans, many of them well-meaning, who believe that whatever hardships the Cuban people suffer are because of the trade embargo, and they have little or nothing to say about the repression, the abuse, the discrimination and the corruption that goes on in Cuba right under our eyes.”

Cuba’s one-party state imposes limits on freedom of speech, assembly and the press. The Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation, a Havana-based group not recognized by the Cuban government, reported more than 5,000 “arbitrary” arrests and short-term detentions in 2017. Amnesty International’s latest human rights report on countries across the world knocked Cuba’s government for frequently silencing opposition through “arbitrary detentions, discriminatory dismissals from state jobs, and harassment in self-employment.”

Calzon says his organization supports an end to the embargo, under the conditions that the Cuban government release all “political prisoners,” raise the salaries of Cuban workers and allow more international humanitarian groups to enter the country.

Carla Riehle, a member of the Minnesota Cuba Committee, acknowledges that US solidarity groups are primarily not made of Cuban Americans, though she said her group works with some.

“Many Cubans are here — certainly those who came earlier [in the 1960s] — because they oppose the Cuban government,” she said.

Nimtz, for his part, equates Cuba’s civil liberties restrictions with polls that show majorities in the US ranking national security issues over their own civil liberties. A 2016 Pew Research Center survey, for example, found 56 percent of respondents in the US said that national security measures had not gone far enough to prevent terrorism compared to just 28 percent who said they went too far in restricting civil liberties. The situation in Cuba, Nimtz argues, is similar in that “most Cubans see these are necessary evils in order to defend their revolution from a very hostile government 90 miles away.”

Not all people active in the Cuba solidarity groups have to think this way. Roberto Fonts occasionally attends Minnesota Cuba Committee meetings and has been doing so for the past few years. He came to the US in 1980 as a part of the Mariel boatlift mass exodus for personal and economic reasons. Fonts grew up in Cuba during the early years of the revolution, which he says attempted to make “a beautiful world created with tremendous intentions.

“I love my country for standing up for itself and saying, ‘This is our country, we’re going to do what we’re going to do,’” he says.

But by the 1970s, Fonts became disillusioned by those he deems opportunists holding important ranks in the Cuban government. Today, he says he wants Cuba to become “socialist and a democracy, where people can express themselves, people can have a voice, where someone else isn’t telling you what to do.”

The US economic system, Fonts says, is good with margin management and finances.

“But we don’t have the structure of social responsibility — we’re deficient at that,” he says. “Cuba has a lot of that. What Cuba’s offering the US is an incredible model to shift that.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!