A global sand grab is wrecking ecosystems and communities around the world

Sand is gathered at a sand mining operation in Rangkasbitung, Indonesia. A global building boom has driven soaring demand for sand for concrete and land reclamation, much of it illegal and damaging to ecosystems and communities.

Deep in rural Cambodia, Chan Vanna pushes his longtail boat through the calm waters of the Koh Kong estuary. Until about 10 years ago, Vanna made a living fishing here, providing for his wife, Wid, and their seven children. Then one day, he says, giant machines showed up at their small inlet and started dredging sand from the bottom of the river.

“They never discussed with our community,” Vanna says. “They came to dredge and the land fell down. And the water became deep.”

The land “fell down” because the dredging caused the riverbanks to wash away.

Now, Vanna says, there are no fish, because without any shallow water, they have nowhere to spawn.

On the nearby shore, small, gaunt children dance to a boombox while the adults snack on longan fruit. They, too, have lost their livelihoods. One of the men, Sa Lee, points to the other side of the river.

The water here “used to be maybe half a meter deep,” he says, “so we could cross over.”

No more. The water is now 10 meters deep — almost 100 feet. What was once a creek is now a wide river. Sa says many of the trees that protected the land have died. Even the crocodiles left.

It’s a scene that’s been repeated throughout coastal Cambodia for a decade. And not just here, but also in Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar and Malaysia and beyond. Rampant and often illegal dredging is part of a global sand grab that has made sand the second-most widely consumed natural resource after water.

“Cities are basically built out of sand,” says Vince Beiser, author of the forthcoming book “The World In A Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization.” “Every concrete building that you see, every mile of asphalt road between those building, all the windows in all those buildings, it’s all made from sand.”

Quartz sand, in particular — the kind usually found on beaches and in rivers — is used in concrete construction worldwide. And there’s an unprecedented demand for it. The skylines of Phnom Penh and Ho Chi Minh City are unrecognizable from just a few years ago. Same with newly-urban areas in India and throughout Africa, not to mention the insta-cities popping up all over China.

It’s the same urbanization that happened in the West over the course of a century, says Beiser. But it’s happening way too fast for nature to keep up, and in places where there isn’t a lot of government oversight.

“There are fewer regulations to protect the environment, and in a lot of places there just isn’t as much enforcement because there’s a lot of corruption,” Beiser says. “And in some places, like India in particular, the business has become so lucrative that a lot of the business is actually controlled by what they call ‘sand mafias.’”

Here in Southeast Asia, much of the finger-pointing about sand is directed at Singapore. But it’s not just about new buildings. The island city-state itself has expanded by 20 percent over the last 50 years, purely through sand-based land reclamation.

“Singapore didn’t have its own resources of sand, so it had to take it from their neighbors,” says Alex Davidson of Mother Nature Cambodia, an activist group that started protesting sand exports a few years ago. “And of course they took it from places like Koh Kong where there’s corruption, a lot of communities can be repressed.”

Under pressure from groups like Mother Nature, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia have recently banned sand exports to Singapore.

Related:The world’s deadly war over sand: 7 things you need to know

For its part, the Singaporean government says all of its sand imports from around Southeast Asia have been legal. But it doesn’t seem eager to talk about the issue. The Ministry of National Development declined requests for an interview. But it knows it has a sand problem.

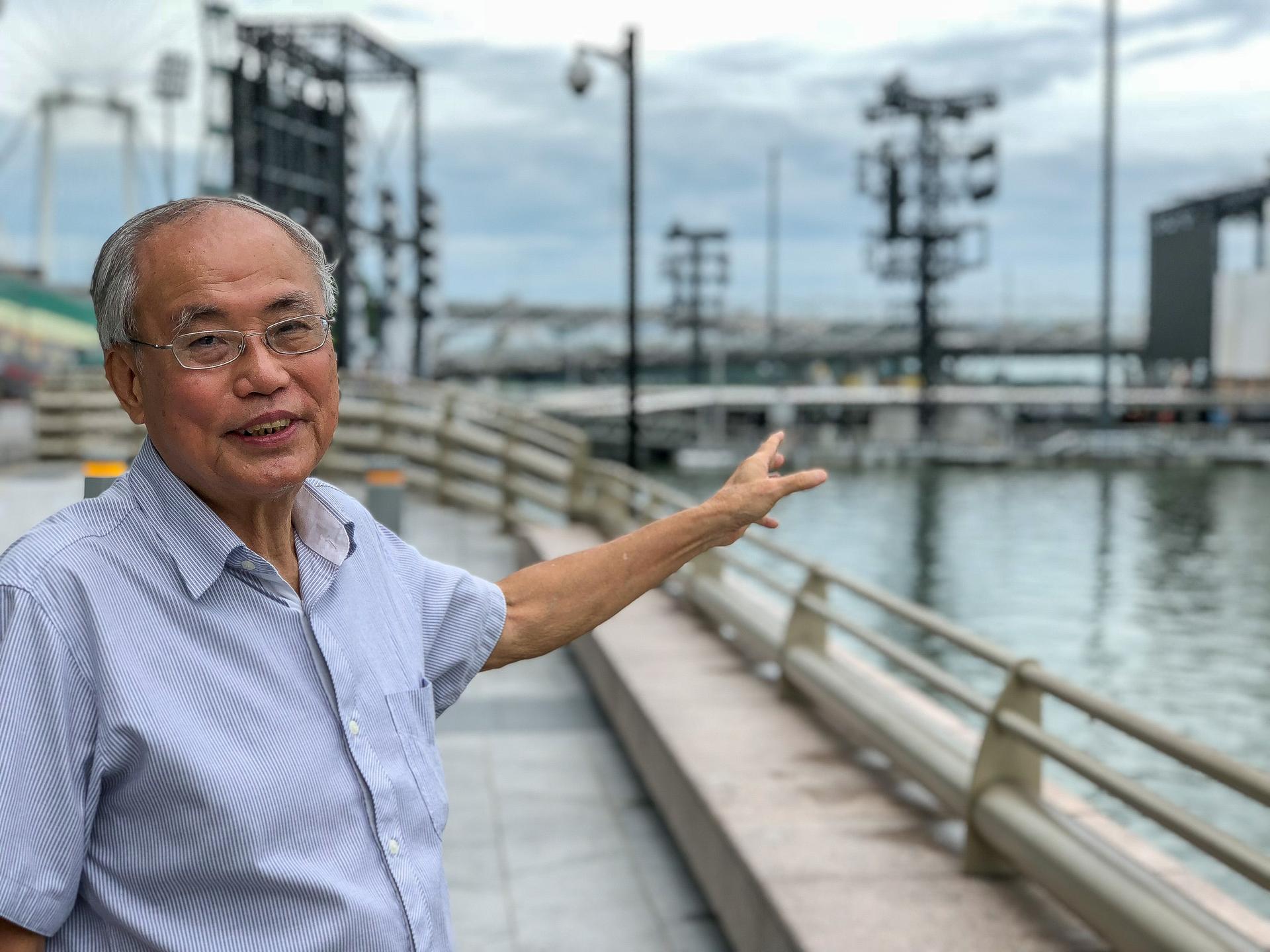

“It’s becoming an embarrassment to Singapore that we are importing so much sand at the expense of our neighbors,” says Singaporean engineer Lim Soon Heng, looking out across the city’s Marina Bay, an area that not long ago didn’t exist.

“Where we are now is all reclaimed land,” he says.

Even after all its recent growth, Singapore’s government estimates it will need to add another 22 square miles to its current borders to accommodate population growth. Lim runs a company that is trying to convince the city-state to do some of that expansion with floating pontoons.

Pontoon technology uses a lot less sand than traditional land reclamation. It’s already being used in massive port projects in the US and Europe, and even in one project here, an entertainment and sports venue.

But it’s been a tough sell.

“The reception is not very overwhelming because [people] don’t understand,” Lim says. “They say, ‘It’s not safe, it will wobble around.’ Well, you can see the structure there is not wobbling.”

The jury is still out on pontoon building here. But other less sand-intensive approaches to expanding Singapore might catch on. Among other things, the government has hired a Dutch company to develop one new site using a method called poldering, which encloses and drains part of the seabed rather than filling it.

Meanwhile, scientists are working on new kinds of building materials for all those new structures. Some would use less sand than concrete, others would use different kinds of sand that are less environmentally sensitive.

It’s not like cities are going to stop building, and Vince Beiser says the real question is how to do it sustainably, instead of turning sand into something of a new sort of conflict mineral.

“Quartz sand is literally the most abundant thing on the planet,” Beiser says. “We have more of it than we have anything else. And if we’re running out [of] that, which we are, we’re really in trouble.“