Despite accord, peace in Colombia is tenuous as country heads to runoff election

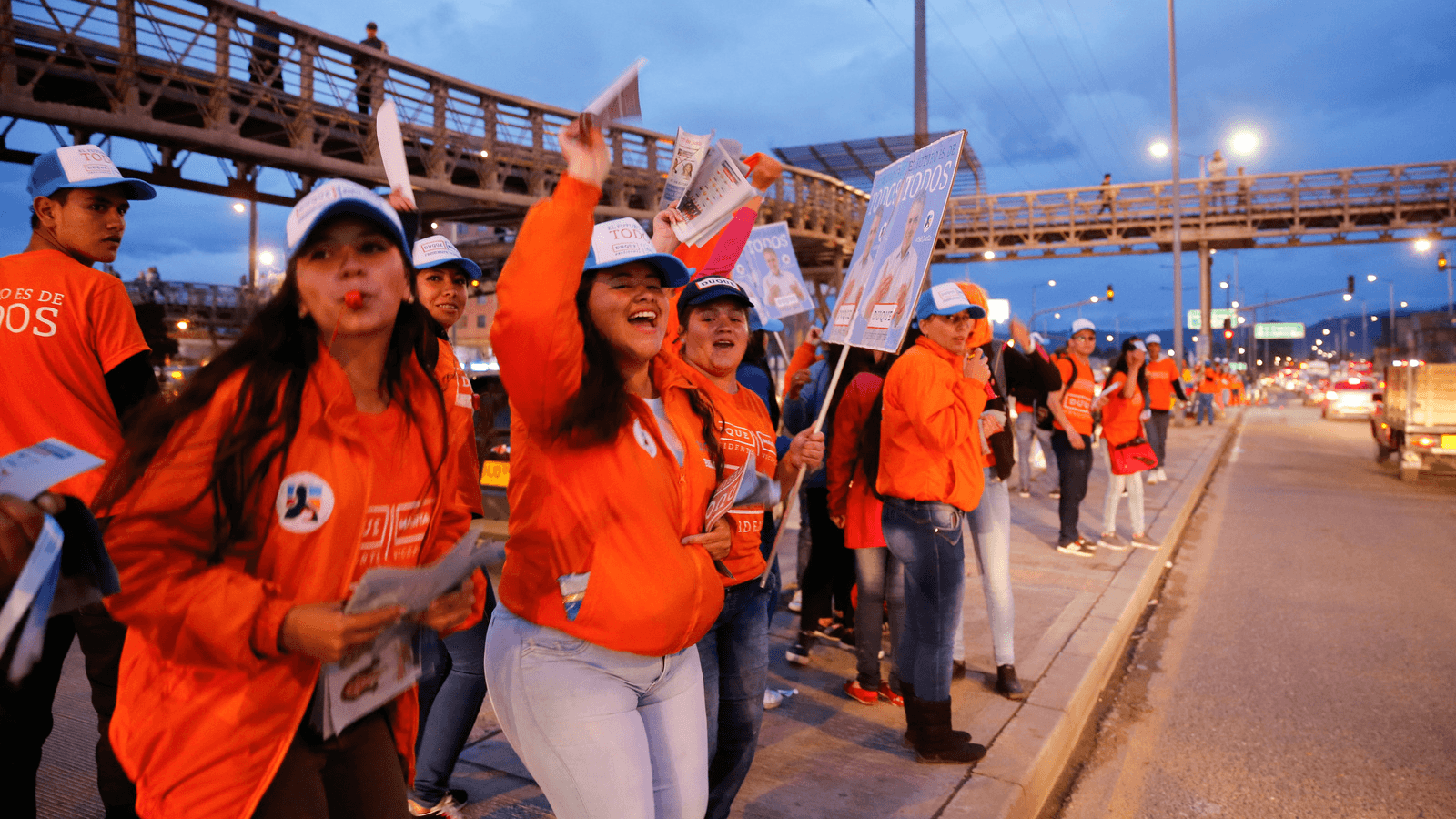

Supporters cheer with the leaflets and placards ahead of the second round of presidential election in Soacha, Colombia, June 11, 2018.

Fewer than two years after the signing of a peace treaty between the Colombian government and FARC rebels, a presidential election has made the accord’s future uncertain.

The leading candidate, Iván Duque, pledges to make changes to the same peace accord that won current President Juan Manuel Santos the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize. Duque is leading the polls after getting 39 percent of the votes in the first round of elections last month. A runoff election is scheduled for June 17.

“A candidate against the peace process … might be elected the next president of Colombia. This speaks to the tremendous reservation that the population has towards the peace process,” said Arlene Tickner, a professor and international relations expert at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia.

Colombian citizens originally rejected the peace treaty, with more than 50 percent voting against it. However, Santos drafted a revised version, which was approved by Congress — but did not return to the people for a popular vote.

Bypassing the people’s vote “adds to the bad taste that exists over this peace treaty,” said voter Jorge Guevara, a developer in the construction industry who lives in Bogotá, though he left Colombia in 1990 for many years after the FARC kidnapped a family member.

He underscored the importance of peace for Colombia, but “the will of the people must be respected,” added Guevara, who was sitting at an outdoor table on a recent evening in an upscale park in Bogotá’s north side.

Close by, Néstor Díaz, who was taking a walk in the park, also said this wasn’t the version of peace he wanted. He said too many concessions have been given to the FARC guerrillas, who make up a smaller percentage of the population.

“They say the voice of the people is the voice of God,” Díaz said. “We all agree that there should be peace, but it has to be without injustices. Peace has to benefit the majority, not the minority. That’s what democracy is about.”

The FARC are now a political party called the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común, or the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force. Formerly it was Colombia’s largest guerrilla group — the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia.

Voters like Guevara and Díaz support candidate Ivan Duque’s opposition to a provision in the accord that allows former FARC combatants to run for public office, including the presidency and Congress, before serving sentences for their crimes.

The treaty sets aside 10 congressional seats for FARC members over the next two terms, which last through 2026, including five seats each in both the House and Senate. Rodrigo Londoño, known by his nom de guerre, Timochenko, originally ran for president but dropped out in early 2018 due to health issues.

Duque opposes the idea of someone like Londoño running for president. Duque, a lawyer who worked at the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, DC, and served one term as senator from 2014 to 2018, says guerrilla fighters who are found guilty of crimes against humanity should spend time in prison before Congress.

“What we want is to make clear that a Colombia of peace is a Colombia in which peace meets justice, where there’s truth, reparations and enforced sentences,” he said in Spanish while giving a speech from a podium after the first election night on May 27. Duque also clarified that he and his supporters do not want to destroy the peace accord altogether.

Despite these concerns, the peace treaty has ushered in more tolerance for left-leaning politicians in Colombia, who had been seen as sympathetic to the guerrillas, Arlene Tickner says. Gustavo Petro, Duque’s opponent, is a left-wing candidate who served a term as mayor of Bogotá until 2015 and used to be in the M-19 guerrilla group that disarmed in 1990.

Alvaro Antolinez supports Petro and also approves of the peace treaty. He’s a fruit vendor in a low-income neighborhood of Bogotá called Kennedy.

“The peace treaty is really good for the country. Which country doesn’t benefit from peace? Which country benefits from war?” Antolinez said while placing fruit in his cart. “Always, when there’s war, there are losers, and never winners. If Duque wins and he brings down the peace treaty, the violence will come back and the country won’t prosper. I don’t know one country — like Iraq, like Colombia — that progresses with war. Not one.”

Petro is supportive of the peace treaty as it was signed. Duque, however, wants the former guerrillas to pay reparations to victims and not be excused from jail time. Most Colombians want former rebels convicted of war crimes to serve jail time.

“Those seats in Congress should not be occupied by persons who have committed crimes against humanity,” Duque said in a television interview with Univision on May 29, shortly after the first election.

The former guerrilla members who will serve in the Congress are unpopular: They won less than 1 percent of the national vote when they ran for those allotted House and Senate races earlier this year in March. When the new Congress begins its term in July, one of those 10 seats will be empty. The FARC member known by the nom de guerre Jesús Santrich was detained after the US Drug Enforcement Administration and the US District Court in the Southern District of New York accused him of trying to export cocaine to the United States. Santrich was part of the FARC team that negotiated the peace treaty.

Rebels sentenced to community service, not prison

Under the accord, former guerrillas convicted of war crimes and who confess to their crimes can be tried by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, known in Colombia as the JEP, its acronym in Spanish. Instead of jail time, the magistrates could decide to give sentences such as landmine removal to people convicted of war crimes. Convicts would be able to serve their sentences and still keep their seats in the Congress.

“This, without a doubt, doesn’t make sense to people and infuriates a large part of Colombians,” says María Victoria Llorente, executive director of Fundación Ideas Para La Paz, an independent think tank based in Bogotá focused on peace-building.

Llorente says Duque would likely need a strong majority in the Congress to implement the changes he seeks.

Despite the uncertainty, David Cortright, who directs the Peace Accords Matrix at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and has been involved in Colombia’s peace process, says more than 20 percent of the peace treaty has already been implemented.

“We’re only in the early stages of implementation — about the 17th month of the process,” Cortright explains. “Normally these peace agreements take 10 to 15 years to reach a high state of implementation, especially one like the Colombian accord that is so complex.

“We’ve seen no indication that the FARC are pulling back or making a decision not to continue implementing its side of the peace agreement,” Cortright continued. “They have at lot at stake in continuing the process.”

Duque’s opponent, Gustavo Petro, who won 25 percent of the vote in the first round, says there’s still work to be done to achieve permanent peace. In an interview with Univision after the first election last month, he pointed out that FARC dissidents have taken up arms and other militant groups like the ELN, or National Liberation Army, are still armed.

The fact that Colombia still has armed militants makes Arturo Morales, a mattress vendor in Bogotá’s Kennedy neighborhood, doubt that the treaty will truly accomplish an end to violence.

“Go look, the guerrillas are still in the mountains,” Morales said. “The guerrillas just call themselves something else, but they’re still trafficking coca. They have no incentive for peace.”

Another element of the treaty focuses on substituting illegal crops by paying farmers to voluntarily replace their coca with cacao or other legal crops. During the campaign, Duque has said that this should be a mandatory substitution, noting a recent spike in coca planting.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Colombia’s coca crops grew from 96,000 hectares in 2015 to 146,000 hectares in 2016. That’s a 52 percent increase.

The election is not only about the peace treaty. The economy is another chief concern, especially in the face of neighboring Venezuela’s economic collapse and the subsequent large-scale migration of Venezuelans to Colombia; some voters fear that Colombia could follow in Venezuela’s footsteps if a right-wing president fails to take the helm.

The polarizing issues at play in this election have led to higher voter turnout. Colombia has notoriously high abstention rates – as high as 60 percent in recent elections. In this election, however, 53 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot, according to the National Civil Registry.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?