Saving Kerala’s Fresh Water

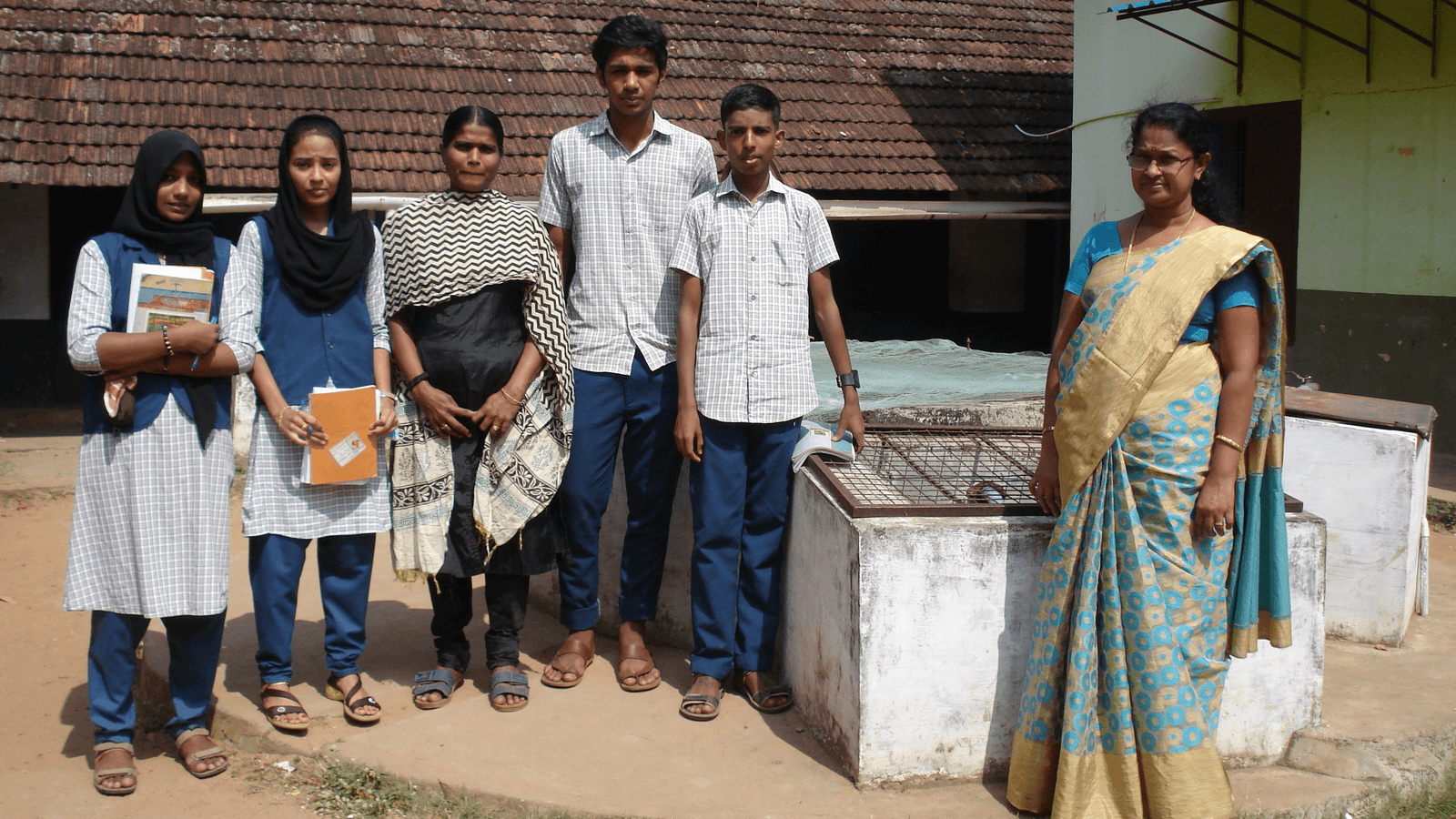

Students stand in front of their high school’s well in Kerala, India. The well provides all of the school’s basic water needs.

Heavy monsoons are typical in Kerala, India, where the rain irrigates crops and fills drinking wells. But over the past decade, the rains have been more volatile, partly due to a changing climate. The unreliable rains have heightened fears of drought, which could be devastating for an area trying to increase its organic agricultural production.

Along with a completely organic agricultural sector, water conservation is now one of the state’s top goals under the Green Kerala program — and individual farmers are crafting their own unique methods to help reach that goal. The heavy rains mean water-intensive crops like rice are the staple cereal grain. And though the amount of water for these crops is not necessarily a problem, capturing it and conserving it does come with its own challenges, especially in an area that is rapidly urbanizing.

In the hills of the Thrissur district, a farmer named Vargheese Tharakan grows bananas by digging trenches across the steep slope on his land, which captures the rainwater so it can percolate slowly underground. When the monsoon hits, water pools in the trenches, which are about two feet deep, and help keep the hillside lush with fruit.

Related: Kerala’s making an ambitious pledge to go organic

Not only do Vargheese’s methods keep his own farm productive, the benefits also reach the farmers downhill. Jos Raphael, a rainwater management expert, has been watching Vargheese’s farm develop for the last few years. He says that before Vargheese took over the barren hill above the village, the wells ran dry. But now after the monsoon, the rain from the trenches reaches the farms below, feeding those crops before finally flowing out the Arabian sea.

At Jos Raphael’s own home, he uses a system of gutters and PVC pipes to catch the rain and fill the well in his garden and a motor to pump water up to the large rooftop bank. Jos Raphael says that people used to collect rainwater from their homes, but with increasing development, urbanization and piped water, this became an obsolete practice.

“India used to collect rainwater for the domestic use, then what happened, the shift took place in the 1950s, this modernization and piped supply and dams and canal irrigation system,” Raphael said. “When the people start to get the water in the homesteads, the people tend to ignore their homestead wells, so the traditional wisdom of harvesting rainwater within the homestead the people tend to forget.”

Deforestation in the Western Ghats, the mountains above the Thrissur district, has also reduced the amount of water retained and increased erosion. To combat these issues, Jos Raphael works for a nonprofit that installs traditional water-harvesting techniques for city municipalities.

“We’ve got a project in Thrissur district administration called Mazhapolima — that means ‘the bountiful rain,’ so we are trying to harvest this rainwater as well as we promote the homestead watershed approaches so that the rainwater in the homestead is conserved,” Raphael said.

Related: In Kerala, a push for organic food turns professionals into gardeners

One of the projects, for instance, at a public government high school uses a similar system of PVC pipes on the roof to collect rainwater, which directs the water through charcoal filters to a large well in the courtyard, helping to increase the level of groundwater. Today, the well can provide all the basic needs of the school.

Fabien Pannikaveetil, an 18-year-old student at the school, says the system also helps serve the city’s poor population. The NGO also gives gutters and pipes to students to install at their parents’ homes and to the laborers who live around the school who don’t have the cash to buy their own systems. It’s organizations like Jos’s that help keep the traditional methods of water management alive in the city, where they have largely been forgotten.

While the village populations are working on water conservation in the hills, further down towards the coast lies another impediment to water protection: the destruction of mangrove swamps. In addition to providing a natural barrier to storms and a nursery for baby fish, mangroves help prevent saltwater from leaking into drinking water. Now with the mangroves’ ongoing destruction, coupled with rising sea levels, there’s increasing salinity in fresh water in districts near the coast.

Many Keralans are concerned about the mangroves’ destruction, not only in terms of what it means for their drinking water but also for livelihoods that depend on the ecosystem, such as fishing. The state government, under the Green Kerala program, ranks protecting species and conserving clean water as high priorities, but Ravi Panakhal says that it’s not enough. A retired army colonel, Ravi now heads the NGO Nature, Environment and Wildlife Society of India, which works at a coastal plot to involve local schools in replanting the mangroves. Ravi says the mangrove area requires high levels of protection.

“This is 234 acres of land […] there. What we want, actually we want a protected area, to protect the livelihood of the people and to serve mankind as well as the existing species. If we keep the mangroves in the belt of this area, the fishing — because actually, these people were making [their] livelihood from the fishes — that will improve and the coastal area will be protected.” Panakhal said.

Tourist condos, hotels and restaurants bring in cash to undeveloped areas like these coastal marshes in this part of Kerala. But development can also be damaging to nature and, in turn, harm human health. Many Keralans are aware of that problem and are trying to conserve nature and water by many different methods from high up in the hills to the mangroves at the coast below.

And that’s why farmer Vargheese Tharakan believes that preserving the natural environment and growing food, if universally practiced, has the power to do nothing less than transform civilization and society.

“Peaceful world” says Tharakan. “Standard studying agriculture, one subject, compulsory all over world — after then — peaceful world.”

A version of this story originally appeared on Living on Earth.