The man who taught the Kremlin how to win the internet

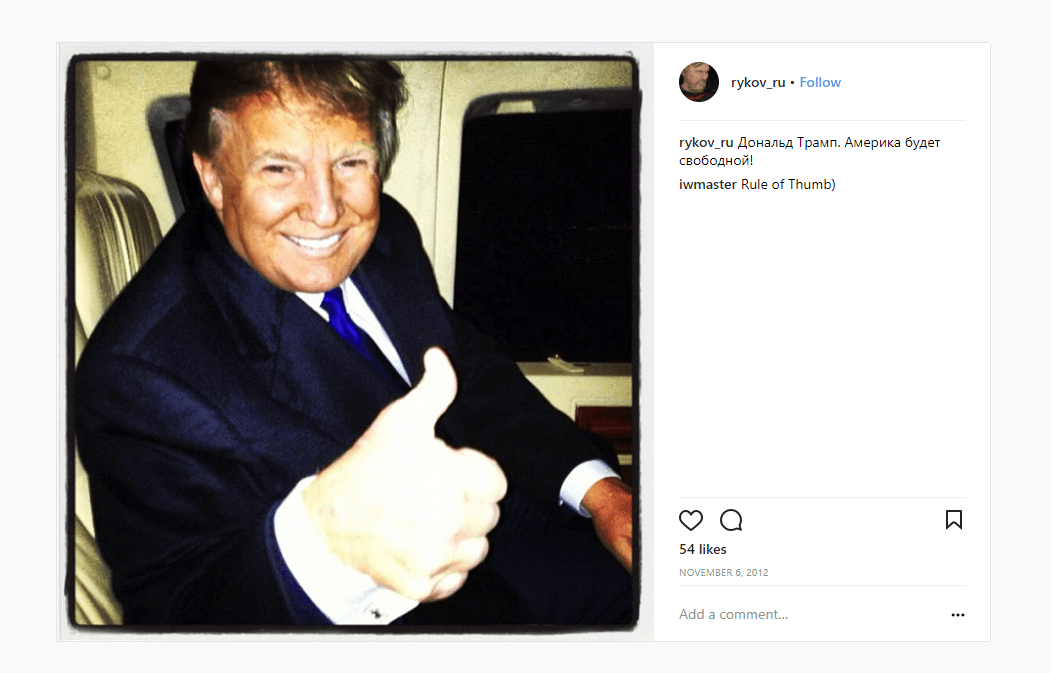

Konstantin Rykov posted a photo of President Donald Trump ahead of the 2016 US presidential election. Rykov claims he helped Trump win.

Konstantin Rykov understands the art of trolling on the internet. Rykov’s knack for creating caustic, snarky, attention-grabbing content made him millions as an internet entrepreneur and got him elected to the Russian Parliament. And now, the Russian government understands the art of trolling too.

Rykov first went online in the mid-1990s. He quickly became fluent in the language of a Russian internet subculture.

He started by creating sites like idiot.ru, and later founded an online prostitution delivery service in Moscow called “Dosug.” He developed personas on Russian social media sites like Vkontakte, Live Journal, and Odnoklassniki, where he accrued large followings by sharing pictures of scantily clad women, telling crude jokes and spreading a satiric, nihilistic brand of humor.

Putin’s government notices Rykov

Rykov eventually made his way into more mainstream Russian media, joining Russia’s state-owned Channel 1 as the head of the internet department. In 2005, he started an online newspaper called “Vzglyad,” which quickly became a propaganda outlet for the Kremlin. President Vladimir Putin’s former deputy chief of staff, Vladislav Surkov, maintained direct lines with Vzglyad’s editorial department and shaped what they published.

“There were weekly meetings at the presidential administration,” said Alexander Shmelev, the editor-in-chief of Vzglyad in 2007-2008. “Sometimes, there were situations when we published something, and Surkov’s assistant who was in charge of the media, Alexey Chesnakov, called and said, ‘No, please, replace this article,’ or, ‘Please, publish something about this issue.’”

The Russian government’s manipulation of Vzglyad’s content was so blatant that it made Shmelev quit the paper. He left Vzglyad after his short tenure as editor-in-chief and joined an anti-Kremlin opposition movement.

Putin’s clamp down on internet media marked a change of course for his administration. After Putin first got elected president in 2000, the political discourse on the Russian internet was largely critical of Putin and his party, United Russia. The opposition movement dominated social media and political blogs.

Initially Putin’s government let this criticism flow freely. Even though Putin had been tightening state control over Russian media since he was elected president, he focused mostly on traditional TV and print news media. The internet was outside Putin’s comfort zone. He reportedly didn’t use a computer for his first few years as president.

Putin shifts attention to the internet

But geopolitical unrest put an end to the Putin administration’s laissez-faire attitude toward online news media. First, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets in Kiev to contest the election of the Russian-backed presidential candidate in 2004. Political activists in Ukraine relied on the internet to organize these protests. In 2008, Russia began a military occupation of South Ossetia in Georgia that continues to this day. The information that spread around the internet portrayed the Russian military as aggressors, not protectors.

Putin’s government realized that it was losing popular support online. Alexander Shmelev remembers being in a meeting with the administration in 2008.

“It was discussed that we lost the information war — that on the internet, everyone around the world believes that Russia suddenly attacked Georgia, and the topic of Georgia attacking South Ossetia is never mentioned and that we came to protect it,” Shmelev said of the meeting. “We need to change this somehow, we need to learn to be proactive, we need to learn to work not only in the Russian segment of the internet but in the internet in general.”

When Putin’s administration decided to change its tactics on the internet, they needed to enlist the help of people who understood how to make information go viral. Someone like Konstantin Rykov. Under the guidance of Surkov, Putin’s government started showing signs of interest in Rykov.

In 2007, Surkov organized private fundraisers for Rykov’s ventures. Rykov was elected to the Russian Parliament in 2008 as a member of the United Russia party, the same party as Putin. Rykov was only 28-years-old.

In return, Rykov developed tactics to help the Kremlin boost support for its image online. Shmelev says that he attracted a new community of supporters for the government by advertising pro-Kremlin articles on sites like Mail.ru, porn websites and humor websites. Rykov showed the Kremlin how to spread competing narratives on social media to deflect attention away from reporting that was critical of their activities.

Russia annexes Crimea, a troll army is born

The Russian government used these kinds of disinformation campaigns to its advantage when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

“I saw people claiming the CIA had put dead bodies inside a plane and purposely shot it down to create propaganda against the Russian government,” said Sri Preston Kulkarni, the campaign director for the Ukraine Communications Task Force, recalling the shootdown of a Malaysia Airlines flight over Ukraine. “That seemed to me beyond any measure of credibility, but people were repeating that story again and again. … And I realized we had gone through the looking glass at that point and that if people could believe that, they could believe almost anything.”

They artificially inflated pro-Kremlin support on the internet, enlisting armies of troll accounts to spread pro-Kremlin narratives on social media and blogs. Some of these trolls were automated bot accounts, but others were human, like Rykov.

Rykov was on the front lines of the information war on social media, spreading stories that made Russia look good and Ukraine’s allies look bad. At that point Rykov was active on international social media platforms, like Twitter and Facebook, where he engaged directly with top US officials on foreign policy issues. It was a new kind of information warfare, and the US government had to figure out a new strategy for dealing with it.

“We spent a lot of time thinking about him and his colleagues in terms of what were their objectives,” says Michael McFaul, US Ambassador to Russia from 2012 to 2014. “He was very active talking about foreign policy in particular. And was he paid, coordinated … these are the fuzzy lines that the Putin government deliberately keeps fuzzy.”

Rykov builds a website for President Trump

In 2015, Rykov did what he does best, built a new website. This one was called Trump2016.ru. This marked the beginning of Rykov’s active campaigning for Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential run. While the impact of Rykov’s campaigning is unknown, Rykov has boasted that he is responsible for helping Trump take the White House. While that claim may be far-fetched, Rykov’s influence on Russia’s online strategy is undeniable.

Wojciech Oleksiak and Evgenyi Klimakin contributed reporting to this story.

A previous version of this story misstated Russia’s actions with regards to South Ossetia in 2008. Russia never annexed the country, but it did stage a military occupation that continues.