Colombian high court grants personhood to Amazon rainforest in case against country’s government

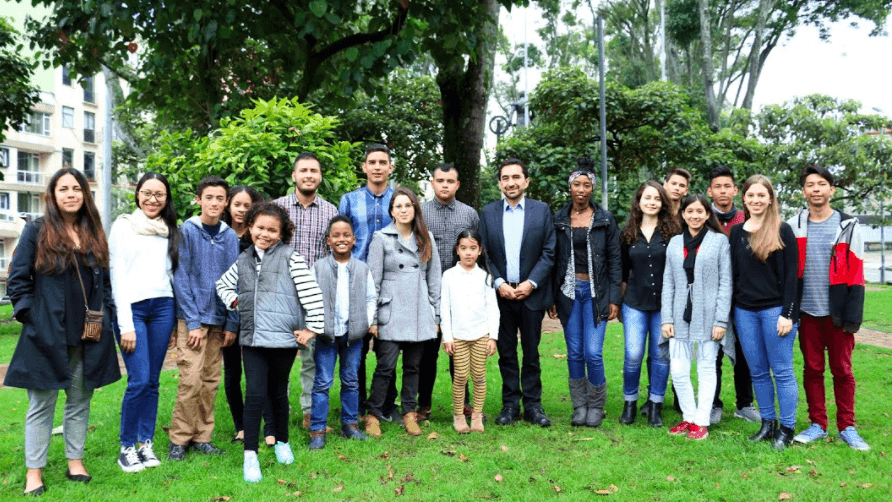

The 25 youth plaintiffs represent 17 cities in Colombia, including four within the Amazon rainforest.

They have been around since the dawn of time, but until 25 years ago certain natural habitats never had rights — at least, not in a legal sense.

That changed in a landmark legal challenge in the Philippines in 1993, when a lawyer named Tony Oposa represented his children and another group of children in a case that argued that deforestation practices in their country violated the children’s rights to live in a healthy environment under the Filipino Constitution. The Supreme Court of the Philippines sided with Oposa and the children.

Recently, history repeated itself in Colombia, where 25 children and young people — ranging in age from 7 to 26 — sued their nation’s government for their right to a safe environment. Their lawsuit, led by the a human rights organization Dejusticia, focused on the rights of the Amazon rainforest itself. After listening to the case, last month the Colombian Supreme Court granted personhood to the portion of the rainforest within the country’s borders, giving it rights under law.

“It's important because we can show that we as young people — and especially for someone that is 7 years old — he doesn't have to be a president or a minister to make a change and to be listened [to]. So, you don't have to have power to create something big,” said lead plaintiff Valentina Rozo of the court’s decision when it was announced.

David Boyd, who authored “The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World,” says there have been several cases where children have sued their respective governments to protect their rights to grow up in a healthy environment. Such cases have been decided in Uganda and Ukraine, with another pending in Portugal and yet another in the United States.

The Colombian case is the first time a direct connection has been made between deforestation and climate change, says Boyd, who is also an associate professor of law, policy and sustainability at the University of British Columbia.

“The court really goes into great detail talking about how it's absolutely vital for the government not only to stop deforestation, but for society more broadly to reevaluate and reorient our relationship with the natural world,” Boyd says. “For too long, we've seen nature as merely a basket of commodities or natural resources for human beings’ use and exploitation. And what the court says is, nature is actually a community to which we belong, and not a commodity for us to exploit."

“And in recognizing that the Amazon rainforest has the legal rights of a person, what that does is that shifts our relationship with nature in a profound way and says, we have really sacred legal obligations to protect and restore the Amazon rainforest,” he adds.

Boyd says giving the rainforest personhood status and legally enforceable rights “is quite a game changer from legal perspective,” given that if the Colombian fails to develop an actual plan to address the issue of deforestation, lawyers can go back into the court and demand action on behalf of the children.

The tandem of dual recognition — for both the rights of the nature and children’s rights to a health climate — can turn out to be “a really explosive mix of transformative potential” in regards to our collective ecological perspective, Boyd says.

As part of the judgment, the Colombian Supreme Court mandated that the country’s leaders (namely the president, minister of environment and minister of agriculture) to begin making an actionable plan involving collaborations with indigenous peoples of the Amazon, local communities and scientists within 48 hours of the ruling — putting the Colombian government, in Boyd’s words, “on a very tight leash.”

Rulings such as the one in Colombia, Boyd says, point to a universal truth that has been around long before the court systems came into existence: that everything on the planet is connected.

“We all are related. We all emerged from the primordial soup billions of years ago,” Boyd says. “We've, of course, evolved in different ways, but we are, scientifically speaking, part of the family of life on this planet. And for far too long we’ve behaved quite selfishly and really, recognizing the rights of nature is just a way of returning to a perspective that says this is our family and we're going to treat our family with respect.”

This article is based off an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?