French Political Cartoonist Tomi Ungerer’s First Retrospective in US

Children of the 60s, 70s, and 80s know Tomi Ungerer as an illustrator of kids’ books like Flat Stanley, The Mellops series, and Crictor. But Ungerer is more than an illustrator — and much of his work is not kid-friendly.Starting in the 1960s, Ungerer created political posters and satirical cartoons that viciously attacked the violent, grotesque, and depraved parts of modern life. After last week’s massacre at the Paris offices of the newspaperCharlie Hebdo, Ungerer’s work seems especially timely. And on Friday, the 83-year-old Ungerer will receive his first U.S. museum retrospective at the Drawing Center in New York, “Tomi Ungerer: All in One.”

As a child in Strasbourg, France, Ungerer discovered the work of cartoonist Saul Steinbergand 19th-century artistHonor Daumier, who both became important influences. Ungerer was nine years old when the Nazis annexed Strasbourg, and he drew cartoons mocking Hitler — drawingswhich might have put himself and his family in danger, had they been found. “Even at that time, he had a political outlook,” says the curator of the Drawing Center exhibit, Claire Gilman.

As a young man, Ungerermoved to New York and worked in advertising — his ads for the New York Times are delightfully playful, nothing like the Gray Lady’s current bland respectability.

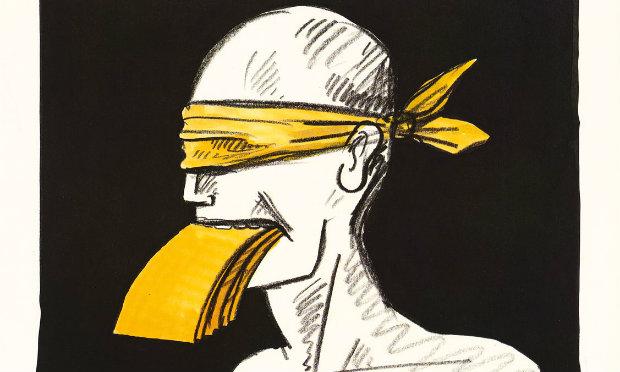

But he also produced scathing cartoons that lampooned the greed, hypocrisy, and soullessnessof New York’s high society. “He’s willing to take it to the edge where it becomes somewhat disturbing and we are somewhat uncomfortable,” Gilman says of Ungerer’s satirical drawings. “It’s about revealing the underside of things.”

In 1967, Columbia University commissioned Ungerer to make a series of posters protesting the war in Vietnam. But the posters hecame up with were too raw for Columbia’s taste, according to Gilman. “They were deemed too outrageous, too difficult, too harsh to be used,” she says.

Some of the examples in the exhibit are, indeed, harsh: one shows the Statue of Liberty being shoved down the throat of a Vietnamese person. Another depicts an American bomber pilot stenciling pictures of children (presumably the pilot’s victims) on the side of a plane.

Unlike his send-ups of the rich and powerful, Ungerer’s political cartoons weren’t supposed to be funny, Gilman argues; they’re intentionally disturbing. “What’s so amazing is he presents things that other people might find offensive to even depict,” Gilman says. “There’s kind of an amazing bravery there.” She argues that Ungerer intendedthe Vietnam posters to be shocking.

What links Ungerer’s political posters, his satirical cartoons, and his darker-than-average children’s books is thatinterest in representing the “underside of things.” “He wants to give life to the repressed, to the abnormal, to what we consider the taboo,” Gilman says. Ungerer shares that taboo-breaking spirit with the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo, whose satire frequently crossed lines of taste.

In response to the massacre, Ungerer made a drawing in solidarity with the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo. In it, the Statue of Liberty has been nailed to a cross. “Liberty crucified,” the caption reads, in French. The message is ambiguous — it could apply equally well to government censorship as a terror attack on free speech. “Though the drawing was spurred by recent events, it could have been executed years ago, and refers to a recurring problem,” says the wall text next to the cartoon. Ungerer has “this great sense of humanity, a great feeling of responsibility for the world,” Gilmansays. “He’s deeply against violence, racism, and injustice of all kinds.”