Why bland American beer is here to stay

Americans tend to prefer beers that have corn or rice "adjuncts," or fillers.

Although craft beer has experienced explosive market growth over the past 25 years, the vast majority of Americans still don’t drink it.

Only about 1 in 8 beers sold in America is a craft beer. For the first time, the three best-selling beers in America are light beers: Bud Light, Coors Light and Miller Lite. Bud Light alone has a greater market share than all craft beers combined.

So while the selection has broadened dramatically, most people’s tastes have not. Even craft beer companies are adjusting to this reality: A recent Chicago Tribune article noted that craft breweries are releasing beers that are “less hoppy and in-your-face” in order to appeal to the majority of Americans who prefer “big corporate lagers.”

In other words, they’re brewing blander beers.

How did Americans come to prefer such bland beer? As an economic historian, I’ve extensively researched the political economy of alcohol prohibition, and the unique history of the US temperance movement might bear some responsibility for country’s exceptionally bland beer.

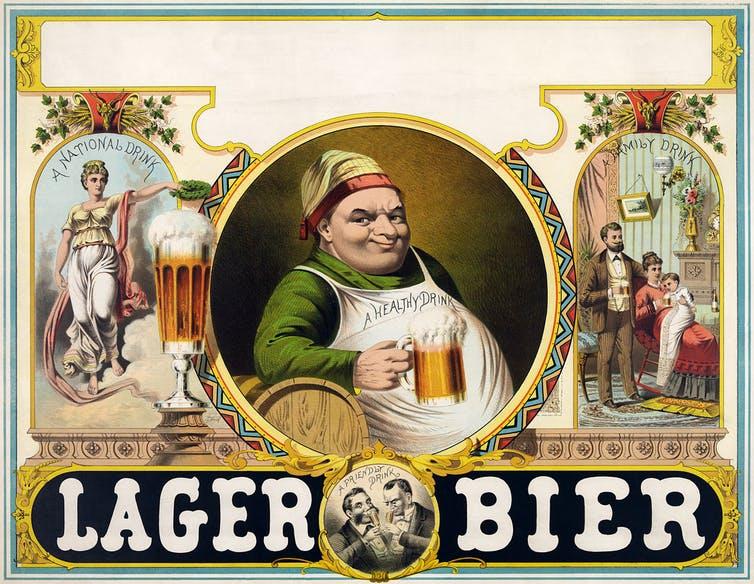

The ‘lager bier craze’ clashes with teetotalers

Unlike European countries with beer preferences and styles that have evolved over centuries, America lacks a homegrown brewing tradition.

The classic American beer is an “adjunct pilsner,” which means that some of the malted barley is replaced with corn or rice. The effect is a beer that’s lighter, clearer and less hoppy than its counterparts in countries like England, Germany and Belgium.

Related: Europeans are embracing American craft beer. So, why are exports trailing off?

In colonial America, English-style beers and ales predominated, but rum and then whiskey were the drink of choice. Cider, easier to make at home, overtook beer by the early 19th century.

However, the American beer market grew during the great mid-19th century wave of German immigration. German lagers were an immediate hit, partially because the German brewing method of bottom fermentation — which involves a relatively long fermentation period and cold storage — made for a more consistent, storable product than top-fermented ales. The lagers were also mellower, though they were dark and hearty compared to what would become popular later.

But the “lager bier craze” dovetailed with another big trend: the temperance movement, which at various times sought to reduce problem drinking, reduce drinking more generally and eradicate alcohol consumption completely. From 1830 to 1845, the temperance movement gained momentum as more and more Americans were taking voluntary “temperance pledges” and giving up spirits and cider.

German brewers always maintained that beer was a “temperance beverage,” unlike ardent spirits such as whiskey. And indeed, European temperance movements did tend to regard beer as relatively harmless.

But activists in the American temperance movement — which by then had become more about abstinence and intertwined with evangelical Protestantism — didn’t buy the argument. The 1850s saw the first big push for state-level prohibition laws, which ended up being passed in a handful of states. Those laws didn’t last for a variety of reasons (including the Civil War), but they did serve notice to the brewers that they needed to work harder to convince the public that beer was a temperance beverage.

Perfect for a midday drink

In the 1870s, American beer would become mellower still with the advent of a new type of lager: the Bohemian pilsner. Clearer, lighter and blander than the Bavarian lagers that had previously dominated the market, pilsners looked cleaner, healthier, more stable and less intoxicating.

As an 1878 issue of the trade publication Western Brewer noted, Americans “want a clear beer of light color, mild and not too bitter taste.”

Brewers and drinkers who wanted to avert the temperance movement’s gaze naturally chose light pilsners over dark lagers. But lighter beer also was a good fit for the long hours of American factory workers, many of whom ate at saloons between shifts. Coming back to work drunk could get you fired, so if you wanted a beer or two with the salty saloon fare, the weakest beers were the best bet.

Pragmatism and personal taste soon became intertwined. Anheuser-Busch introduced Budweiser in 1876 — whose rice adjuncts produced an even milder beer — to great success. Pabst Blue Ribbon, with its corn adjuncts, became a national sensation as well.

In 1916, Gustave Pabst, the son of Pabst Blue Ribbon’s founder Frederick Pabst, told the United States Brewers Association that “the discrimination in favor of light beers (is strongest) in those countries where the anti-alcohol sentiment is strongest.”

Nonetheless, the drumbeat of the temperance movement started getting louder.

Prohibition leaves its mark

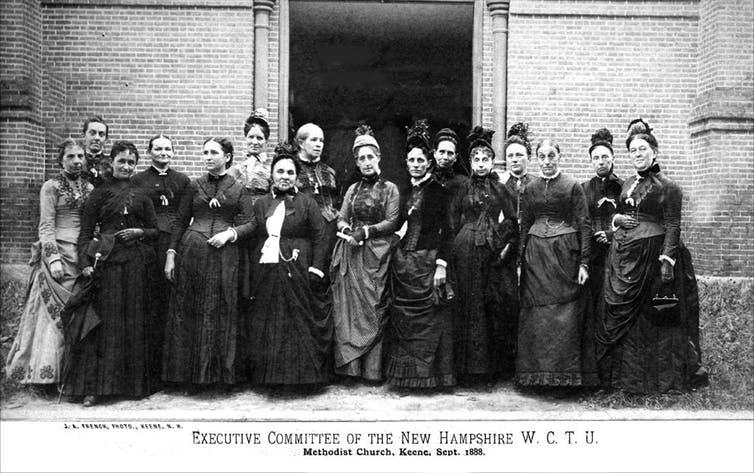

By the late 19th and early 20th century, the temperance movement had returned in force. Efficient organizing campaigns by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League led to a new wave of state and local prohibitions and, finally, a push for national prohibition.

National constitutional prohibition, as decreed by the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, was devastating to the beer industry in the short term. But in the long term, it further laid the groundwork for a nation of bland beer drinkers.

Careful estimates by economist Clark Warburton found that alcohol consumption during Prohibition may have actually risen for wine and spirits but fell by two-thirds for beer, which was harder to conceal. Although Prohibition may have introduced a generation of young people to cocktails, they had hardly any exposure to beer – and certainly hadn’t acquired the taste for hearty beer.

In March 1933, eight months before the 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition, Congress modified the Volstead Act to allow the production of “non-intoxicating,” low-alcohol beer and wine, with a maximum of 4 percent alcohol by volume.

The new, watered-down beer was a huge hit with the public, which hadn’t tasted a full-strength legal beer since 1917. Dark beers and ales had accounted for some 15 percent of the market before World War I. But in 1936 their share was just 2 to 3 percent. In 1947, researchers at Schwarz Laboratories analyzed the alcohol, hop and malt content of American beers in the 1930s and 1940s and remarked that many of these early post-repeal beers were “too hoppy,” “too heavy and too filling” for consumers’ tastes. The report noted “a corrective trend” in which brewers sharply reduced their hop and malt content.

More adventurous brewers and drinkers were also stymied by post-Prohibition laws. State and federal policies effectively banned homebrewing, and most states required a “three-tier” system of brewers, distributors and retailers that made it more difficult to make and market specialty beers.

The blandification of American beer continued for another 70 years. During World War II, American troops got 4 percent alcohol beer in their rations, exposing yet another generation to the joys of weak beer. The hop and malt content of beer fell sharply and steadily over this period. Hop content fell by half from 1948 to 1969, and the rise of “lite” beer in the 1970s accelerated the trend. Hop content fell 35 percent from 1970 to 2004.

Despite the phenomenal rise of craft beer, light beers are still dominant. The craft beer explosion is a remarkable story, but perhaps we should stop calling it a revolution.

![]() For now, bland beers are still king.

For now, bland beers are still king.

Ranjit Dighe is a pofessor of economics at State University of New York Oswego

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.