There are no surprises in Russia’s upcoming elections. Putin will win.

Opposition leader Alexey Navalny has energized younger Russians despite being banned from the race. Here, at a protest in central Moscow, attendees hold signs reading “It’s no choice and I won’t come" and "Elections without a choice" in support of Navalny’s calls for a boycott.

Russian voters go the polls on March 18 to choose a president, but there’s not much to truly decide.

Vladimir Putin will win his fourth term after 18 years in power. But behind the scenes of an election with a foregone conclusion — an event that should be drama-free — a more complicated picture emerges.

For Putin, the real concern is not winning but the optics of how the race is won. Turnout — getting enough people out to vote to make this victory feel like a mandate — is key to giving his fourth term a legitimacy the Kremlin clearly craves.

Related: In Russia, a 'ghost empire' rises

In recent weeks, everything from sponsored lotteries to free medical check-ups to food discounts have been used to lure Russians to the polls on Sunday. Kremlin officials promise a record turnout.

But many acknowledge an enthusiasm gap for Putin after so many years dominating Russia’s political scene.

“I do respect Vladimir Putin. He did a lot for the country,” says Slava Nesterov, a 29-year-old artist who lives in Moscow. “But I was 10 years old when he was elected. Power should change hands from time to time. Otherwise, you end up with stagnation.”

That sentiment is at the heart of Nesterov’s project, “Putin Every Day,” an imagined (but very real gift) calendar that tracks Putin’s hold on power far beyond Sunday and into the year 2120.

“It’s not meant to insult the president, but there should be new people in the political scene,” Nesterov says.

Simulated competition?

Alexey Navalny, the opposition leader and arguably Putin’s only true political rival, has been barred from the race on a legal technicality. In response, he has called for a nationwide boycott of the election — arguing attentive vote monitoring will take the shine off Putin approval ratings that, Navalny argues, are inflated by state polling, media and manipulation.

Other candidates, by turn, appear as simulated competition who pose no threat. Fundamentally, observers agree that the candidates are either in the race — or allowed to be in the race — simply to generate public interest.

Take celebrity-socialite-turned-newcomer candidate Ksenia Sobchak. Sobchak has used the election season to attack Putin’s positions on everything from the annexation of Crimea (she’s against it) to LGBT rights (she’s for them). But Sobchak is also running a conceptual “Against All” campaign given Navalny’s absence from the ballot. Her father, former St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak, was Putin’s mentor — a fact that raises questions about her motives.

Pavel Grudinin, a successful businessman who made his fortune reviving a Soviet-era collective farm, now tops the Communist Party ticket and has generated some genuine voter curiosity. Or he did — until state television ran an expose claiming he had foreign bank accounts.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who has run in every election since 2000, is also back again. The perennial returning candidate is an outrageous nationalist and “official” Kremlin-endorsed court jester whose mission this time seems to be dragging the other candidates down with petty insults. The presidential debates have often devolved into shouting matches or worse.

Putin, of course, doesn’t participate in such electioneering and never has. With few exceptions, he “campaigns” by simply “being president” and defending Russian interests against threats near and far.

Related: Russia’s shadow armies: Soldiers, mercenaries or volunteers?

Earlier this month, he gave a speech in which he unveiled a series of new supposedly invincible super weapons aimed at the US. Putin argued this was in response to missile defense systems that the US had put in place in eastern Europe and Asia.

During one mega-campaign event at Moscow’s central Luzhniki stadium, Putin spoke for all of six minutes — and spent most of those minutes singing the national anthem before departing the stage.

A youthquake

Putin has had to change some tactics to fend off the appeal of leaders like Navalny.

Related: A guide to Russian 'demotivator' memes

Over the past year, Navalny has built an impressive regional movement, managing to bring thousands of Russians in cities across the country out to protest corruption in the Kremlin. Most strikingly, many of his supporters are in their late teens, members of “the Putin Generation” who have only known one leader their entire lives.

The Kremlin has responded by showing that Putin, too, can connect with youth. Despite a well-known aversion to computers and the internet, the Russian leader now regularly litters his speeches with references to cryptocurrencies, digital platforms and innovation.

Russian celebrities, film and pop stars have also been recruited en masse to promote the Russian leader’s cool factor.

For example, the pop group Fabrika (Factory) released a racy video in which the group’s three female members have competing sexual fantasies about their “Vova,” an affectionate term for Vladimir.

The song is but one of several heavy-handed efforts to make the 65-year-old Putin seem like a symbol of the future instead of the past.

Related: A mole among trolls: Inside Russia's online propaganda machine

Yet there are those who argue that Putin’s political system is built to last.

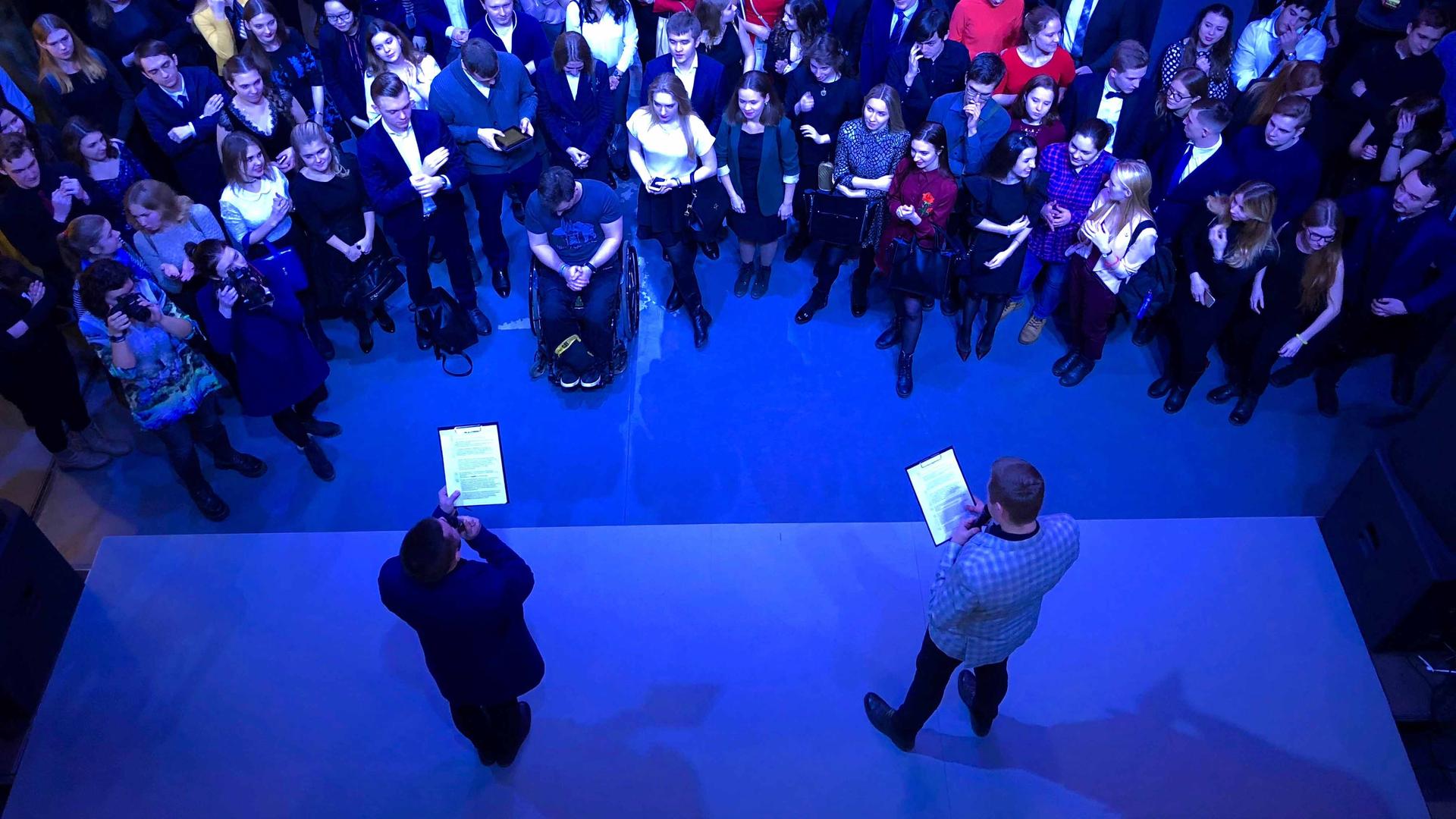

Molodaya Gvardia, or Young Guards, the youth wing of Putin’s United Russia party, seems intent on injecting new blood and energy into Russian official politics. At a recent Moscow meet-up for “young parliamentarians,” members touted the various internship opportunities and competitive grants available for young Russians with ideas and drive to improve the country.

That includes Ekaterina, a 23-year-old member of the organization who declined to give her last name. Originally from Russia’s Caucasus region, she insists that the stability of Putin’s rule has opened up endless opportunities.

“I remember how my parents struggled in the 1990s,” she says. “But I can realize my dreams, and I can travel and I can improve my country.”

To be sure, Molodaya Gvardia presents a positive vision for Russia — perhaps admirably so.

But it’s one that occasionally smacks of cult of personality.

As the evening switched over to a dance party, an image of Putin beamed onto a screen with the slogan: “Knowledge is the Currency of the 21st Century.”

But political currency also comes with a mandate. As Sunday’s results come in, look to voter turnout to determine just how futuristic Putin’s fourth term will be.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?