Meet Doña Luz Jiménez, the forgotten indigenous woman at the heart of Mexico’s cultural revolution

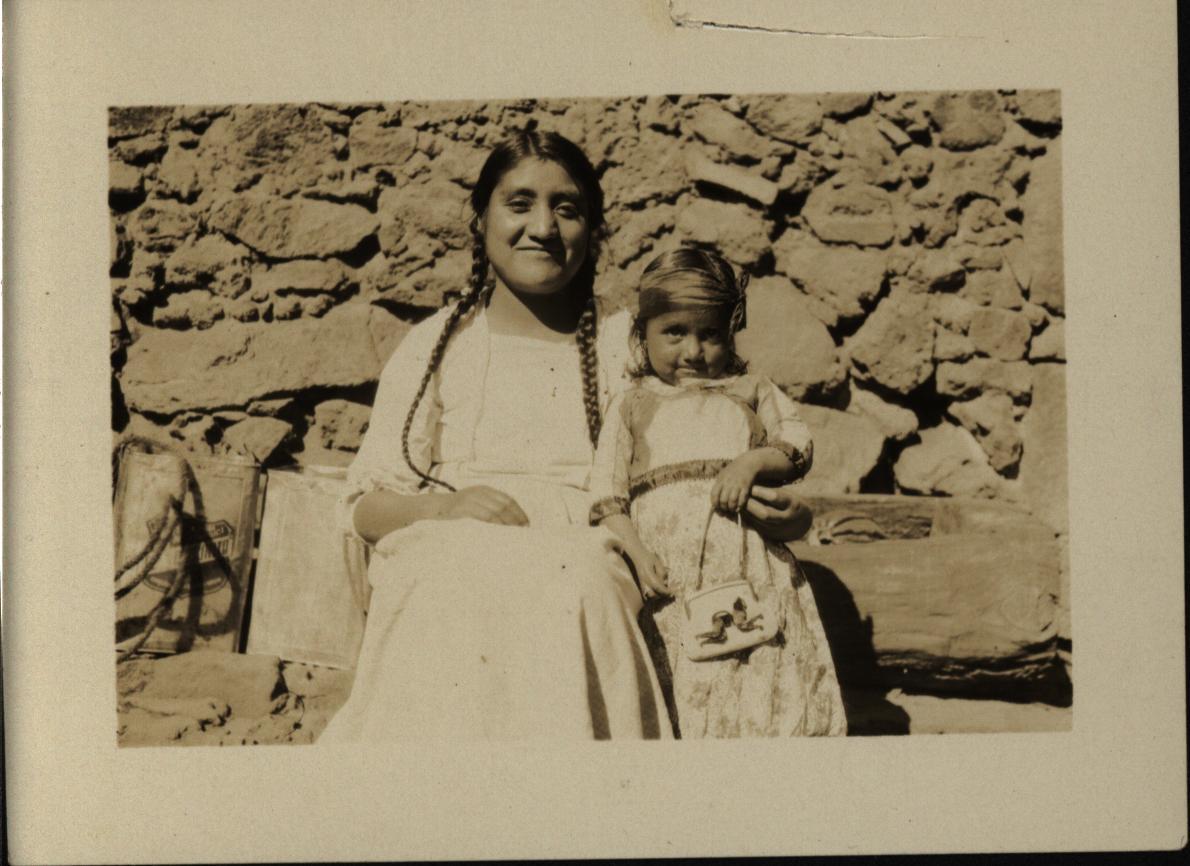

Luz Jiménez early in her modeling career, is shown posing for Ramón Alva de la Canal, Fernando Leal and Francisco Díaz de León at an outdoor painting school in Coyoacán, ca. 1920.

If you’ve ever been to Mexico City, you’ve likely encountered Luz Jiménez, though chances are you don’t know it.

Jiménez, a Nahua woman from humble origins, posed for many of the greats of the Mexican mural movement: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rufino Tamayo and Fernando Leal, to name just a few. Thanks to them, her image adorns the walls of the national palace and other imposing buildings throughout the city’s historic center.

Despite this visibility, Jiménez lived in constant poverty and is scarcely remembered today. The story of how her image became so ubiquitous while she remained so obscure is as complex as the countless works of art in which she appears.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Born to a Nahua family in 1897 and christened Julia Jiménez González, Jiménez's early life and education were rooted in the small farming community of Milpa Alta, just south of Mexico City. Years later, she would recall how her relatively peaceful life was overturned by the Mexican Revolution. Of the violence that suddenly reigned in her once-tranquil home, Jiménez later told anthropologist Fernando Horcasitas: “The heavens did not thunder to warn us that the tempest was coming. We knew nothing about the storms nor about the owlish wickedness of men.”

A massacre at the hands of Venustiano Carranza’s army in 1916 took the lives of Jiménez’s father and all the other men of her village. Devastated and destitute, she was forced to move to Mexico City with her mother and sisters.

There, they struggled to make ends meet, selling bread and artisanal goods on the streets, according to her grandson Jesús Villanueva Hernández. Jiménez caught a break when she won an indigenous beauty contest in 1919. Shortly thereafter, she started going by “Luz” and began modeling at the outdoor painting schools that had sprung up across Mexico City as revolutionary violence transitioned into a decadeslong cultural revolution.

As a semblance of stability slowly returned to Mexico by the early 1920s, artists and intellectuals began to grapple with the question of what it meant to be Mexican in the postrevolutionary social order. A generation of artists occupied themselves with painting these ideas across the walls of the city.

Nahua women came to be seen as symbols of the noble Aztec past at the core of this nascent national identity. Romanticized representations of women wearing traditional indigenous dress began to populate paintings, murals, films and other art and popular culture. While these works cast indigenous people in a relatively positive light, they also promoted the inaccurate stereotype that the only “authentic” Indians lived in rural areas and were, essentially, frozen in the past.

Related: In Florence, they're bringing the works of women artists out of the basement

This was the art world that Jiménez began her career in, and she quickly navigated her way to the center of it. Modeling at an art school in Coyoacán, she quickly became Fernando Leal’s favorite model. Through him, she met Jean Charlot, Diego Rivera and other artists in their circle.

Throughout the 1920s and into the '30s, Luz posed for numerous works of art that to this day adorn the walls of Mexico City. She modeled for Diego Rivera’s first government-commissioned mural, “La Creación” (1922-23), for Leal’s “La Fiesta del Señor de Chalma” (1923-24), and Orozco’s “Cortés y Malinche” (1923-26), murals that continue to draw visitors to the Colegio Antiguo de San Ildefonso in downtown Mexico City.

She was photographed by Edward Weston and Tina Modotti and posed for a regal statue that still stands in the posh neighborhood of Condesa. While Diego Rivera was painting the famous murals that adorn the walls of the National Palace (1929-35), he would send a car to Milpa Alta to retrieve Luz when he needed her to model for him, then host her at his home while he painted her.

But as Jiménez’s image became increasingly more visible, she struggled through poverty and relative obscurity. At 28, she gave birth to her only daughter, Concha, out of wedlock. As a single mother who still supported her own mother and sisters and frequently gave what she could to her community, she constantly struggled to make ends meet. To supplement the meager pay she received as a model, she simultaneously worked as a domestic servant and street vendor. At one point, she was so poor that she had to sleep on the streets in a cardboard box.

Jiménez was a talented model but her real love was teaching, and it’s part of why she was so popular with artists of the cultural revolution. She positioned herself as an educator to a group of muralists and painters eager to infuse their own cultural and artistic sensibilities with indigenous authenticity. As the painter, Jean Charlot, later recalled in an interview with his son, John: “There is a whole image there that she projected. Now, many of the other girls could put their village clothes on and pose with a pot on their shoulders, but they didn’t do it, so to speak, to the manner born. And Luz had one thing that was important: She could do it both naturally, as the Indian girl that she was, and know enough so that she could imagine from the outside, so to speak, what the painters or the writers saw in her, and she helped both see things because of that sort of double outlook she could have on herself and her tradition.”

As a fluent and insightful speaker of Nahuatl, she taught the language to artists during her modeling sessions. Doña Luz or Luciana, as she was affectionately called, was also a weaver, a storyteller and an intellectual in her own right. She modeled not just her body, but also her wealth of cultural knowledge.

Related: The little-known link between Princess Leia’s iconic hairstyle and the Mexican Revolution

Jiménez worked with Charlot for decades and, as years of personal correspondence in the Jean Charlot Collection show, they formed a deep personal connection beyond the art they created together. He was the godfather of her daughter, Concha. She would eventually serve as a beloved nanny to his four children. They stayed in contact for the rest of her life, exchanging letters and photos long after he relocated to the US. He sent money when she needed it and continued to provide support to her family even after her death.

Jiménez's grandson, Jesús Villanueva Hernández, has cultivated a small family archive and has dedicated himself to making his grandmother’s legacy known. In an interview at his home last summer, he spoke about his grandmother: “Luz’s life was really difficult. She had so many hardships: first because of the revolution, then as an indigenous person, as a woman, as a woman who had a baby outside of marriage, as a single mother, as a woman who posed in the nude.”

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

But he discourages the view that it was all adversity or that the artists she modeled for exploited her. Even though the pay was minimal, her work with artists gave her access to cultural capital and a network of support when she needed it most, he claims.

Jiménez’s modeling work also brought her into contact with an intellectual milieu that included anthropologists and linguists. Once they understood the depth of her cultural and linguistic knowledge, members of this group were soon eager to work with her, as well.

Jiménez advised linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf, narrated folktales to anthropologist Robert Barlow and recounted her life story in a series oftestimoniosto Fernando Horcasitas. She also collaborated with Anita Brenner and Jean Charlot to create children’s books based on traditional Nahua stories. But her authorship and intellectual contributions were rarely acknowledged. If she was credited at all, it was more often as an informant than as an author. Despite this lack of recognition, Jiménez took great pride in her work and gained access to intellectual and artistic spaces that typically excluded indigenous peoples altogether.

In 1965, Jiménez was struck by a passing bus after paying a visit to her friend and comadre, Anita Brenner. Jiménez died several days later, on her 68th birthday. Several publications noted the passing of “Rivera’s model,” but she was largely abandoned by public memory shortly thereafter.

In addition to Villanueva Hernández’s efforts,scholars including Frances Karttunen and Kelly McDonough have worked to make Jiménez legacy more visible. In 1999, an exhibition at the Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo briefly put Jiménez's life and work on display. And she is remembered fondly and memorialized by the people of Milpa Alta. But she has, for the most part, been left out of popular understandings of the era she helped shape.

Writing her back into the history of the cultural revolution not only gives Luz Jiménez the credit she deserves — it also enriches our understanding of the remarkable woman and the indigenous knowledge at the heart of one of Mexico’s greatest artistic moments.

Natasha Varner writes more about Luz Jiménez in her book, “La Raza Cosmética: Beauty, Race, and Identity in Revolutionary Mexico,” forthcoming from the University of Arizona Press.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?