Wages for American workers are ticking upward, but the US remains one of the world’s most inequitable nations

Wages for American workers are ticking upwards, but the US remains one of the world’s most inequitable nations, and one with a weak social safety net compared with other Western democracies.

If you’ve been following the plunges in the world’s stock markets, you know what many pundits say triggered the recent turmoil: Wages of American workers are finally starting to tick upward. (This led to fears that a cascade of events could end in rising interest rates and inflation.)

Last week it was reported that average hourly wages of American workers grew 2.9 percent over the past 12 months. It’s a good sign, but American workers still have a lot of catching up to do and income inequality and wage stagnation remain major concerns. President Barack Obama called this “the defining challenge of our time” and Bernie Sanders ran his presidential campaign around combatting inequality.

Consider Marilyn Sorensen, a personal care worker in Denver. She makes beds, does laundry and cooks meals.

“It’s basically the skill of a mother taking care of a baby," Sorensen says. "Some of these people have lost the ability to go to the bathroom on their own, to eat, to speak; a lot of them have cognitive issues.”

She’s 61, and she’s been doing this for more than 20 years. Sorensen, a single mother who also takes care of a grandchild, started at $7 an hour. She now earns $10 an hour. She says she typically works six days and 43 hours a week for an agency.

“How do I get by? It’s isn’t a lot of money,” Sorensen says. “You have to really budget every dime. You have to be vigilant about your transportation, how much gas. I spend a lot of time at home watching TV, crocheting. I have to watch every dime.”

Sorensen’s story is far from unique. Yes, national wages inched up last year. But consider this statistic from Michelle Webster with the Colorado Center on Law & Policy: “In 2016, median earnings for workers in the state were 2 percent less than what they earned in 2000" when adjusted for inflation.

Webster says according to 2016 data, seven out of 10 food service workers in Colorado couldn’t afford a “basic-needs budget” — food, shelter, health care, transportation and other necessities. And yet unemployment in Colorado has been hovering around 2.5 percent.

“I mean, it really is quite shocking, given how strong the economy is here and how wealthy a state we are,” Webster says.

So that’s the picture in Colorado. But how does income inequality in the US overall compare with other nations?

There’s a way to gauge this: It’s called the Gini index and it measures inequality. Using this as a guide, if the US were in the European Union, the US would be the most unequal country by a wide margin: 35 spots behind Lithuania, the EU’s most inequitable country. The US is about on par with Saudi Arabia, Cameroon and Iran.

Another way to gauge inequality is to look at pay for people at the top.

“The best data that we, and others, have is that in the US, CEO to worker ratio is between 250 to 1, to 350 to 1,” says Michael Norton at Harvard’s Business School. “The US is a huge outlier over any country that we have data for.”

So, for example, if a worker in the US is earning $15 an hour, a boss could be taking home around $4,000 or $5,000 … an hour. Or think of it this way: Some CEOs are earning an unskilled worker’s annual income nearly every day.

It’s hard to find an economist, or pretty much anyone, who would say that’s desirable.

Still, on the flipside, Norton says, most people think that too much equality stifles innovation.

“When we do surveys and ask people what they think the ideal level of inequality is, they never say equal, all over the world. No one thinks that everyone should make the same amount of money,” Norton says. “Everybody thinks there should be inequality in an ideal world. It’s just that they think it should be way less than what it is now.”

So, how exactly do you make a society more equal?

One way is to raise the minimum wage, which happened recently in 18 states and 20 cities.

Another way is to raise taxes on the wealthy.

Just over a century ago, Teddy Roosevelt proposed a national income tax on America’s richest, not so much to raise revenue, but to combat rising disparities in wealth. In recent years in France, the government under President Francois Hollande raised the highest income tax bracket to 75 percent. But the government quickly backed off and lowered rates after a couple of years.

But we could never be like France, right?

“In the 1950s, the top [US] tax rate was like 90 percent,” says Norton. “In fact, we’ve done surveys — they don’t believe us that it could’ve ever been that in the United States. It seems so European or something.”

The top marginal tax rate under President Dwight Eisenhower was actually 91 percent.

Today, things are heading in the opposite direction with Congress and President Donald Trump lowering the top tax brackets. And that has many worried that income inequality will only get worse in the US.

President Trump and the Republicans counter that tax cuts will trickle down to the masses in the form of higher wages. (If history is a guide, they won’t.) After the corporate tax cuts, many companies did give employee bonuses, but those are one-time pay bumps.

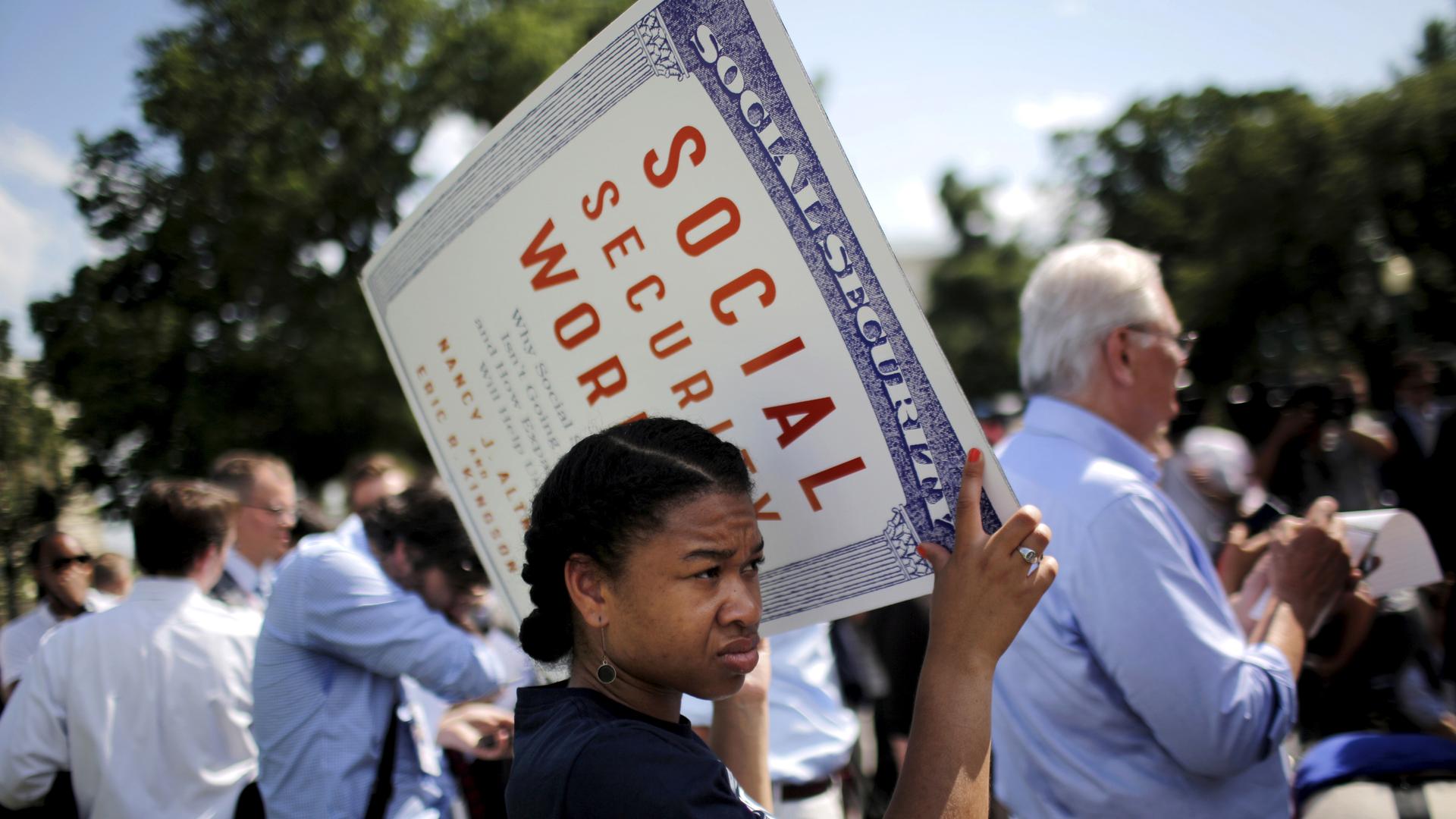

One more way to lessen inequality: Expand the social safety net to be more in line with European nations or Canada. That’s not happening here.

“We’re seeing cuts in lots of different areas, we’re seeing new requirements being put on government-benefit programs,” says Andrea Stiles Pullas, who directs the career development program at the Mi Casa Resource Center in Denver, an organization that helps low-income families with education and job training.

Given the options out there, Stiles Pullas says there’s essentially one solution left to combat income inequality for the working poor.

“So what they do is they’re working two or three jobs," Stiles Pullas says. "That’s what you have to do in Denver, Colorado, these days in order to pay your bills.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?