Foreign experiments with trickle-down tax cuts: A rare proposition for a robust economy

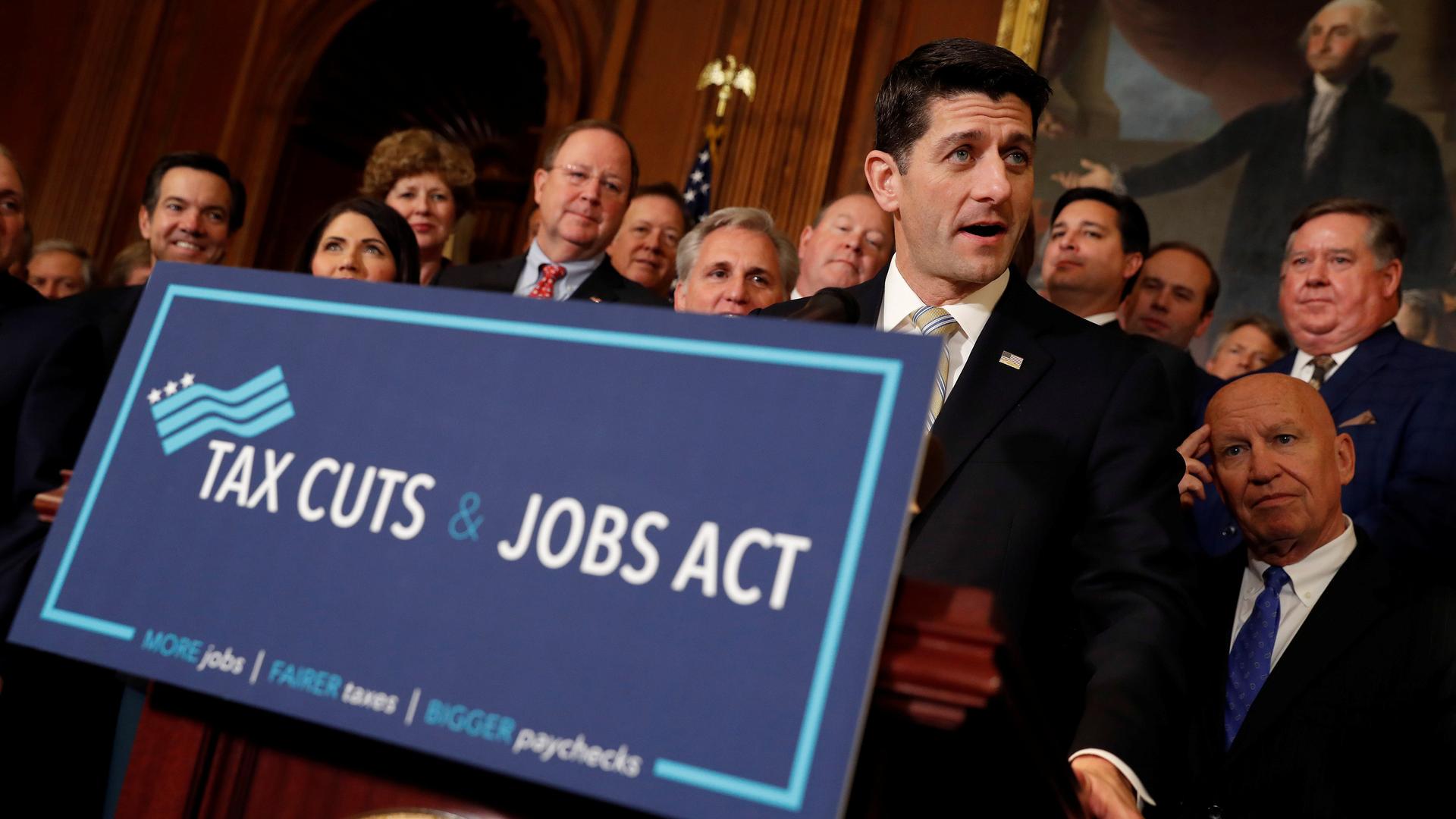

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan speaks at news conference announcing the passage of the "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act" at the US Capitol in Washington, Nov. 16, 2017

In the late 1970s, Ireland’s economy was struggling. So they decided to cut business taxes dramatically while also increasing individual taxes including on the middle class. The idea was that stronger businesses would benefit everyone.

It worked.

“For the following 25 years, they had really rapid economic growth and went from being the poorest country in Europe to one of the richest. It really did help everybody,” said economist James Hines, a tax specialist at the University of Michigan. "Now, Ireland was a very specific situation and the question is whether that kind of lesson would apply to the United States?”

Hines says that’s debatable. The United States isn’t Ireland 40 years ago.

“Unemployment is very low in America right now,” said Hines. “Also, when Ireland cut their business taxes, they did it in a very smart way. They targeted it to foreign manufacturing firms, initially, because they thought that they would get the greatest economic benefits from that, rather than across-the-board cuts. And Ireland coupled that with a lot of very sensible policies that they enacted at the same time.”

Hines doesn’t see anything close to this type of methodical, deliberate policymaking from the current Republican tax proposals.

“It seems that a lot was cobbled together just to try to get passage,” said Hines.

The tax reform in Washington is the latest experiment with trickle-down economics — the idea that if you target tax cuts toward the wealthy, money will trickle down and all will prosper. It's commonly associated with supply-side economics.

Kansas recently experimented with it and the results weren't good — growth lagged, tax revenues fell and the state had to cut spending on education and infrastructure projects. The state legislature ultimately reversed course and raised taxes.

But tax cuts helped a floundering Ireland decades ago. So, have broad tax cuts been tried by other countries to help an already robust economy? I reached out to a handful of tax specialists to pose that question.

“I’m not aware — that doesn’t mean there isn’t — but I’m not aware of such an example,” said David Cay Johnston, editor-in-chief of DCReport.org.

Wayne Winegarden, an economist with the free-market think tank, the Pacific Research Institute, pointed to the Baltic States after the fall of the Soviet Union as a reason to lower taxes. But the Baltic states were radically transforming from socialism to capitalism at the time, so that’s not exactly an apples-to-apples comparison to the US today.

Winegarden mentioned France’s latest experiment with tax cuts, but the jury is still out on how those will work. Winegarden also brought up tax reforms enacted by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s: “That helped incent economic activity, which is exactly what we need now.”

Under Thatcher, Britain’s economy initially got a boost, became more efficient and inflation was checked. But tax reforms there were targeted and incentivized. And economic reforms also brought a lot of social pain: unemployment, rising inequality and the weakening of unions.

Was it worth it? Depends on who you ask.

Britain’s economy was also shrinking in the 1970s. The US economy is growing today, just not as quickly as some believe it can.

Winegarden thinks many deficit projections — adding $1 trillion to $1.4 trillion to the long-term debt — are too high and tax reforms from Washington will provide a bigger boost to the economy than those estimates consider. He adds that the tax reforms also address a spending problem in Washington: “There’s too much money being spent for too little return.”

Johnston doesn't see the rationale for selling the Republican tax reform as a way to boost the economy. “Corporations are sitting on record amounts of cash. If you have an adequate supply of capital, why in the world would you want to do things to encourage a more adequate supply of capital?”

Johnston isn’t an outlier in criticizing today’s Republican tax plans. The University of Chicago polled 38 prominent economists across the ideological spectrum — only one said proposed tax cuts would yield “substantially higher” economic growth.

And unlike Ireland in the 1970s, the US in 2017 is part of a much more interconnected global economy. When US taxes go down, the dollar generally gets stronger. (If taxes were to be cut, it’s very likely that interest rates will rise because there will be a larger deficit and the federal government will have to borrow more money. That will attract capital from abroad, pushing up the value of the dollar.)

“A rising dollar could provide a headwind to the economy,” said Michael Klein, an economist with the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. Klein is also an executive editor of EconoFact, a web publication that analyzes economic social policies.

Klein explained that if the dollar gets stronger, it’s going to make it harder for American companies to export. “So this one goal [of the Trump administration] of having a lot of tax cuts is going to be at odds with another goal of trying to move the trade deficit closer to balance.”

And that means that tax cuts might not boost the economy quite the way Republicans are promising. Of those 38 economists, all of them said the current tax overhaul will make the long-term debt “substantially higher.”

Economists also warn that tax cuts that disproportionately favor the wealthy will also widen income inequality.

Given the academic research, many economists say they feel ignored by Washington right now.

“It’s frustrating that the role of experts, people who have really thought about these things carefully, is down-weighted. And there’s a lot more consensus among economists about a lot of things than would generally be thought,” said Klein.

Now, all of this isn’t to say that economists think tax reform is unnecessary. Far from it.

“We needed to fix the US business tax system to make it more like other countries, to make the United States more competitive,” said James Hines.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle tend to agree with this. In fact, President Barack Obama tried to lower the corporate tax rate from 35 to 28 percent.

Hines said Congress is now missing an opportunity and “made hamburger out of it when they got down to the details.”

“If you have a sensible tax reform combined with other sensible government policies, then you can usually get a pretty good response. The question in America in 2017 is: Is that what we’re getting?”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?