Garry Kasparov and the game of artificial intelligence

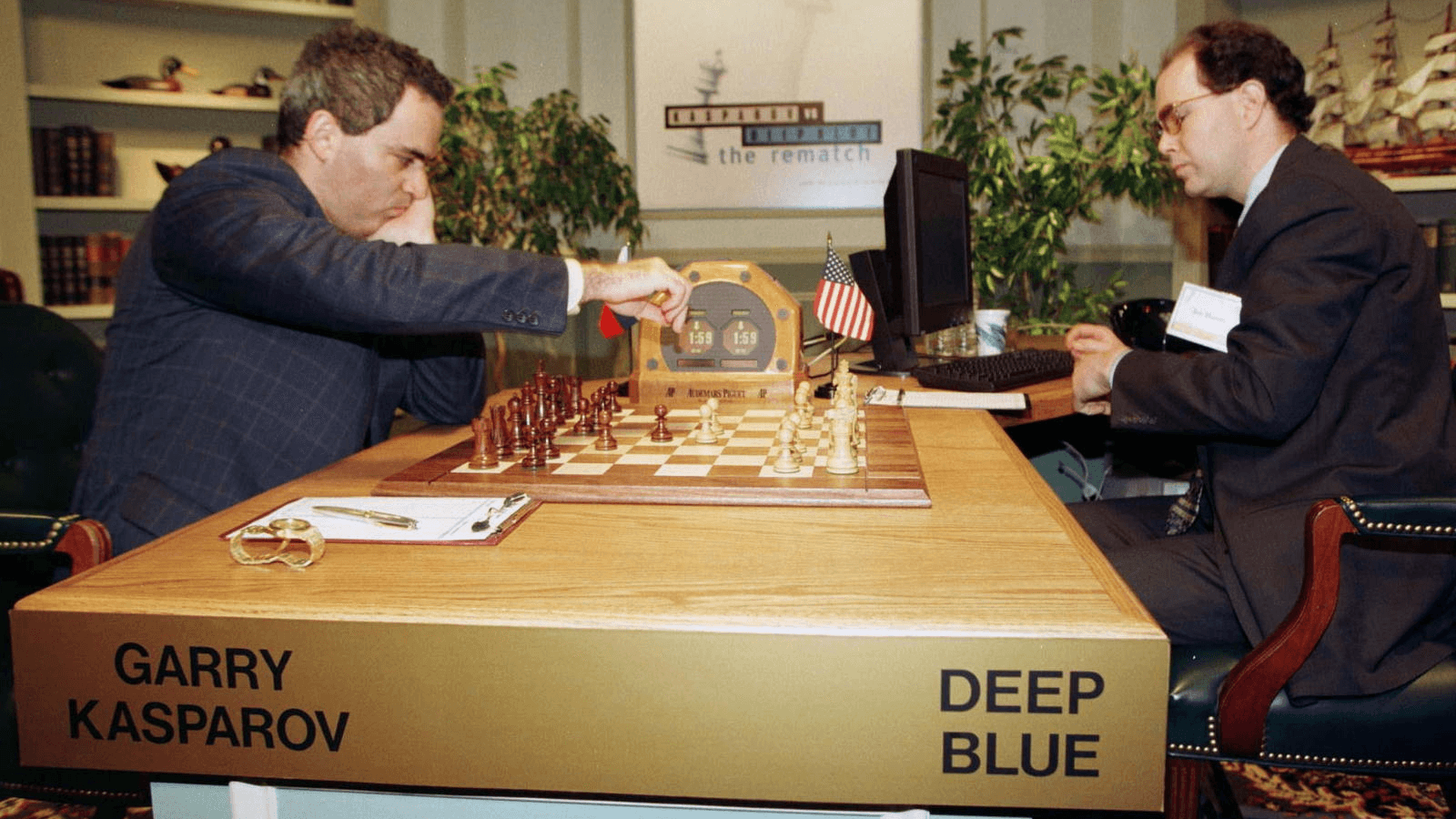

Garry Kasparov faced off against Deep Blue, IBM’s chess-playing computer, in 1997. Deep Blue was able to imagine an average of 200,000,000 positions per second. Kasparov ended up losing the match.

It’s 1997, and Garry Kasparov is hunched over a chessboard, visibly frustrated. He’s fidgeting in between turns and shaking his head in disbelief as he waits for his opponent to put the final touches on an inevitable victory. Finally, Kasparov makes his move, stands up and races away from the board. He raises his arms, astounded that he was beaten by a machine.

His opponent was the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue, a machine that was capable of imagining an average of 200,000,000 positions per second. But going into the match, Kasparov was confident. He was the Michael Jordan of chess at the time. He had been beating chess-playing computers since the ‘80s (he’ll remind you that he defeated an earlier version of Deep Blue in 1996) and was considered nearly unbeatable.

So when Kasparov, one of the greatest chess players of all time, lost to a computer in front of a global audience, people began to wonder whether it was just a matter of time before machines surpassed humans in other aspects of life.

“From the beginning of the computer era, it was a belief that chess could serve as the ultimate test for machine intelligence,” Kasparov says. “And the game of chess has always been seen as the nexus for human intelligence. So when a machine faced a human in chess and won this battle … it could definitely be a revolutionary moment.”

Immediately after the match, Kasparov was bitter. But in the 20 years since, the chess legend has warmed to his place in history. In his new book, “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins,” Kasparov discusses the story of that match and its place in the broader narrative of artificial intelligence.

“If I had to think whether this was a blessing or a curse that I became world champion when machines were really weak, and I ended my professional career when computers were unbeatable, I think it’s more like a blessing,” Kasparov says. “I was part of something unique.”

Kasparov has become even more involved in artificial intelligence over the years. He came up with a concept he calls “advanced chess,” where a human and a computer team up to play against another human and computer. Kasparov says this situation is mutually beneficial: The human player has access to the computer’s ability to calculate moves, while the computer benefits from human intuition.

And chess isn’t the only avenue for this human-machine partnership. Kasparov says this sort of cooperation is possible in everything from diagnostic medicine to manufacturing.

“You’d rather have an experienced nurse working with an algorithm rather than a top professor who might be tempted to challenge a machine’s assumptions,” Kasparov says.

But not everyone shares Kasparov’s optimistic view of a machine-filled future. There are concerns that robots will replace humans in the workforce. Machines are viewed as a looming threat to jobs and the economy.

These days, Kasparov isn’t ruffled by computers. He says humans have always developed machines. And despite concerns throughout history, we have always managed to adapt.

“The difference today is that machines are going after people with college degrees, political influence and Twitter accounts,” Kasparov says. “But this is normal. Any industry that isn’t under pressure from technology is in stagnation.”

That includes the technology industry itself. Last year, DeepMind’s AlphaZero AI beat Stockfish, formerly the world’s top-ranked chess engine. It started with no prior knowledge of chess and needed only four hours of self-training.

A version of this story originally appeared on Innovation Hub.