Venezuela’s new ‘fatherland’ ID card, created with China’s ZTE, helps create social control

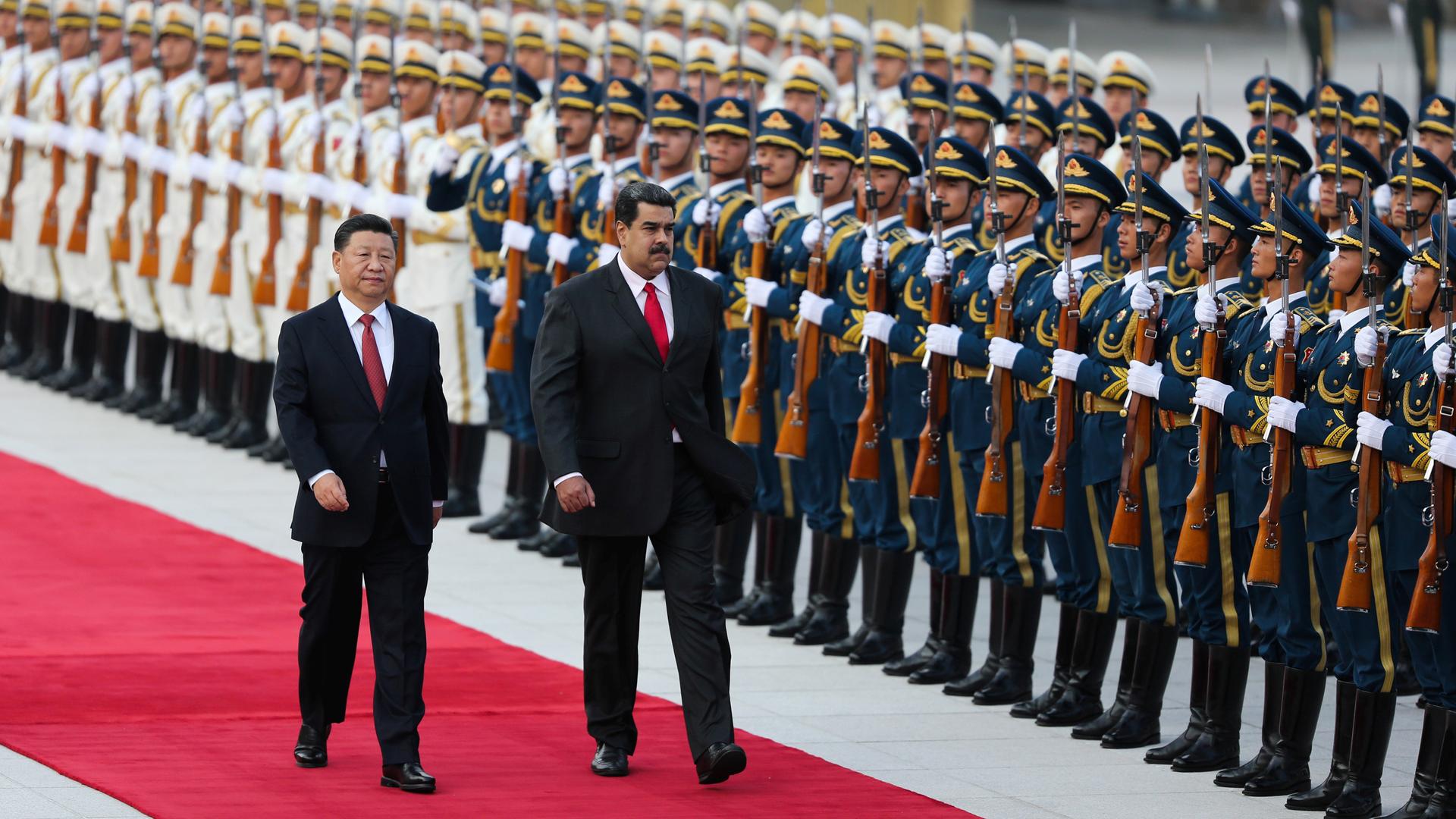

Chinese President Xi Jinping walks next to Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro during his welcoming ceremony in Beijing, China Sept. 14, 2018.

In April 2008, former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez dispatched Justice Ministry officials to visit counterparts in the Chinese technology hub of Shenzhen. Their mission, according to a member of the Venezuela delegation, was to learn the workings of China’s national identity card program.

Chavez, a decade into his self-styled socialist revolution, wanted help to provide ID credentials to the millions of Venezuelans who still lacked basic documentation needed for tasks like voting or opening a bank account. Once in Shenzhen, though, the Venezuelans realized a card could do far more than just identify the recipient.

Related: 5 reasons why Venezuela’s nightmare could get worse

There, at the headquarters of Chinese telecom giant ZTE Corp, they learned how China, using smart cards, was developing a system that would help Beijing track social, political and economic behavior. Using vast databases to store information gathered with the card’s use, a government could monitor everything from a citizen’s personal finances to medical history and voting activity.

“What we saw in China changed everything,” said the member of the Venezuelan delegation, technical advisor Anthony Daquin. His initial amazement, he said, gradually turned to fear that such a system could lead to abuses of privacy by Venezuela’s government. “They were looking to have citizen control.”

The following year, when he raised concerns with Venezuelan officials, Daquin told Reuters, he was detained, beaten and extorted by intelligence agents. They knocked several teeth out with a handgun and accused him of treasonous behavior, Daquin said, prompting him to flee the country.

Related: This Google engineer was asked to create a censored version of Google News for China. He refused.

Government spokespeople had no comment on Daquin’s account.

The project languished.

But 10 years after the Shenzhen trip, Venezuela is rolling out a new, smart-card ID known as the “carnet de la patria,” or “fatherland card.” The ID transmits data about cardholders to computer servers. The card is increasingly linked by the government to subsidized food, health and other social programs most Venezuelans rely on to survive.

Related: Delivering food is now a dangerous job in Venezuela

And ZTE, whose role in the fatherland project is detailed here for the first time, is at the heart of the program.

As part of a $70 million government effort to bolster “national security,” Venezuela last year hired ZTE to build a fatherland database and create a mobile payment system for use with the card, according to contracts reviewed by Reuters.

A team of ZTE employees is now embedded in a special unit within Cantv, the Venezuelan state telecommunications company that manages the database, according to four current and former Cantv employees.

The fatherland card is troubling some citizens and human-rights groups who believe it is a tool for Chavez’s successor, President Nicolas Maduro, to monitor the populace and allocate scarce resources to his loyalists.

“It’s blackmail,” Hector Navarro, one of the founders of the ruling Socialist Party and a former minister under Chavez, said of the fatherland program. “Venezuelans with the cards now have more rights than those without.”

In a phone interview, Su Qingfeng, the head of ZTE’s Venezuela unit, confirmed ZTE sold Caracas servers for the database and is developing the mobile payment application. The company, he said, violated no Chinese or local laws and has no role in how Venezuela collects or uses cardholder data.

Related: Understaffed and overextended: How Venezuela’s oil industry fell apart

“We don’t support the government,” he said. “We are just developing our market.”

An economic meltdown in Venezuela is causing hyperinflation, widespread shortages of food and medicines, and a growing exodus of desperate citizens. Maduro has been sanctioned by the United States and is criticized by governments from France to Canada as increasingly autocratic.

In that, critics say, Maduro has an ally. The fatherland card, they argue, illustrates how China, through state-linked companies like ZTE, exports technological know-how that can help like-minded governments track, reward and punish citizens.

The database, according to employees of the card system and screenshots of user data reviewed by Reuters, stores such details as birthdays, family information, employment and income, property owned, medical history, state benefits received, presence on social media, membership of a political party and whether a person voted.

So far, the government’s disclosure of ZTE’s involvement in the fatherland project has been limited to a passing reference in a February 2017 press release that credited the company with helping to “fortify” the underlying database.

Related: Trump sees opportunity in Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis as midterms approach

Venezuela’s government didn’t respond to requests for comment for this article. Nadia Perez, a spokeswoman for Cantv, the state-run telecoms firm, declined to comment and Manuel Fernandez, the company’s president, didn’t respond to emails or text messages from Reuters. China’s Justice Ministry and its embassy in Caracas didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Although ZTE is publicly traded, a Chinese state company is its largest shareholder and the government is a key client. ZTE has run afoul of Washington before for dealings with authoritarian governments.

The company this year paid $1 billion to settle with the US Commerce Department, one of various penalties after ZTE shipped telecommunications equipment to Iran and North Korea, violating US sanctions and export laws. The Commerce action was sparked by a 2012 Reuters report that ZTE sold Iran a surveillance system, which included US components, to spy on telecommunications by its citizens.

Legal experts in the United States said it is unclear whether ZTE and other companies that supply the fatherland system are violating US sanctions on Venezuelan leaders by providing tools that critics believe strengthen the government’s grip on power.

Fernandez, the Cantv president, is one of the targets of those sanctions because of the telecom company’s censorship of the internet in Venezuela, according to a US Treasury Department statement. But the prohibitions thus far are meant primarily to thwart business with Maduro and other top officials themselves, not regular commerce in Venezuela.

Still, US lawmakers and other critics of Maduro’s rule are concerned about ZTE’s role in Venezuela. “China is in the business of exporting its authoritarianism,” US Senator Marco Rubio told Reuters in an email. “The Maduro regime’s increasing reliance on ZTE in Venezuela is just the latest example of the threat that Chinese state-directed firms pose to US national security interests.”

To understand how the fatherland card works and how it came to be, Reuters reviewed confidential contracts and internal government documents related to its development. Reporters also interviewed dozens of current and former employees of ZTE, Venezuela’s government and Cantv, or Compania Anonima Nacional Telefonos de Venezuela, as the company is formally known.

They confirmed details of the project and the outlines of Daquin’s account of its origins.

“An attempt to control me”

Maduro for the past year has urged citizens to sign up for the new card, calling it essential to “build the new Venezuela.” As many as 18 million people, over half the population, already have, according to government figures.

“With this card, we are going to do everything from now on,” Maduro said on state television last December.

To encourage its adoption, the government has granted cash prizes to cardholders for performing civic duties, like rallying voters. It has also given one-time payouts, such as awarding moms enrolled in the card a Mother’s Day bonus of about $2. The payment, last May, was nearly a monthly minimum wage – enough to buy a carton of eggs, given the current pace of inflation.

Maduro is also taking steps to force the card’s adoption. The government now says Venezuelans need it to receive public benefits including medicine, pensions, food baskets and subsidized fuel. In August, retirees protested outside social security offices and complained the fatherland rule limits access to hard-won pensions.

Benito Urrea, a 76-year-old diabetic, told Reuters a state doctor recently denied him an insulin prescription and called him “right wing” because he hasn’t enrolled. Like some other Venezuelan citizens, especially those who oppose the Maduro administration, Urrea sees the card with suspicion.

“It was an attempt to control me via my needs,” Urrea said in his Caracas apartment. Reuters was unable to contact the doctor.

Using the servers purchased from ZTE, the government is creating a database some citizens fear is identifying Venezuelans who support the government and those who don’t.

Some of the information, such as health data, is gathered with card usage. Some is obtained when citizens enroll. Cardholders and local human rights groups told Reuters that administrators ask questions about income, political activities and social media profiles before issuing the card.

Civil servants are facing particular pressure to enroll, according to more than a dozen state workers.

When scanning their cards during a presidential election last May, employees at several government offices were told by bosses to message photos of themselves at polls back to managers, they said. A Justice Ministry document reviewed by Reuters featured a list of state employees who didn’t vote.

After Chavez became president in 1999, he sought to empower “invisible” Venezuelans who couldn’t access basic services. In the following years, more citizens received documentation, but the cards were fragile and easily forged, according to a 2007 Justice Ministry report.

The report, reviewed by Reuters, recommended a new, microchip-enabled card that would be harder to counterfeit. No such effort got underway.

That December, after nearly a decade of soaring popularity, Chavez suffered his first electoral defeat, losing a referendum to scrap term limits. Oil prices plummeted shortly thereafter, hammering the economy.

Chavez worked to appease his working-class base, including throngs still lacking identity credentials. He sent Daquin, the top information security advisor at the Justice Ministry, to China.

The technology Daquin and colleagues learned about in Shenzhen underpinned what would become China’s “Social Credit System.”

The still-evolving system, part of which uses “smart citizen cards” developed by ZTE, grades citizens based on behavior including financial solvency and political activity. Good behavior can earn citizens discounts on utilities or loans. Bad marks can get them banned from public transport or their kids blocked from top schools.

ZTE executives showed the Venezuelans smart cards embedded with radio-frequency identification, or RFID, a technology that enables monitors through radio waves to track location and data. Other cards used so-called Quick Response, or QR, codes, the matrix barcodes now commonly used to store and process information.

After the trip, Venezuela turned to Cuba, its closest ally, and asked for help creating its own version of RFID cards. “The new goal was Big Data,” Daquin said.

In June 2008, Venezuela agreed to pay a Cuban state company $172 million to develop six million of the cards, according to a copy of the contract. Cuban government officials didn’t respond to questions about the agreement.

By 2009, Daquin grew uneasy about the potential for abuses of citizens’ privacy.

He expressed those concerns to officials including Vladimir Padrino, a general at the time and now Venezuela’s defense minister. The Defense Ministry didn’t respond to phone calls, emails or a letter presented by Reuters for comment.

On the morning of Nov. 12, at his local Caracas bakery, six armed officials in uniforms of Venezuela’s national intelligence agency awaited Daquin, he told Reuters.

They showed him photos of his daughter and forced him to drive east toward the town of Guatire. Off a back road, Daquin said, they beat him with pistols, forced a handgun into his mouth and dislodged several teeth, still missing.

“Why are you betraying the revolution?” one asked.

They demanded $100,000 for his release, Daquin said.

Daquin, who says he had been saving for years to buy property, went home, pulled cash from a safe and delivered it to the men. That evening, he booked a flight for himself, his wife and their three children to the United States, where he has lived since, working as an information security consultant.

His brother, Guy, who also lives in the United States, confirmed Daquin’s account. Documentation reviewed by Reuters corroborates his role at the ministry, and people familiar with Daquin’s work confirmed his involvement in the card project.

After Daquin fled, the Cuban contract went nowhere, according to another former advisor.

In March 2013, Chavez died. Maduro, his heir as Socialist Party candidate, was elected president the next month. The lingering oil crash dragged Venezuela into recession.

“We’ll find out”

With hunger increasing, the government in 2016 launched a program to distribute subsidized food packages. It hired Soltein SA de CV, a company based in Mexico, to design an online platform to track them, according to documents reviewed by Reuters. The platform was the beginning of the database now used for the fatherland system.

Soltein’s directors, according to LinkedIn profiles, are mostly former Cuban state employees. A person who answered a telephone listed for Soltein denied the firm worked on the fatherland system. A woman at the company’s registered address in the resort city of Cancun told Reuters she had never heard of Soltein.

The system worked. Nearly 90 percent of the country’s residents now receive the food packages, according to a study published in February by Andres Bello Catholic University and two other universities.

Now more satisfied with its ability to track handouts, the government sought to know more about the recipients, according to people involved in the project. So it turned back to ZTE.

The Chinese company, now in Venezuela for about a decade, has over 100 employees working in two floors of a Caracas skyscraper. It first worked with Cantv, the telecommunications company, to enable television programming online.

Like many state enterprises in Venezuela, Cantv has grown starved for investment. ZTE became a key partner, taking on many projects that once would have fallen to Cantv itself, people familiar with both companies said.

ZTE is helping the government build six emergency response centers monitoring Venezuela’s major cities, according to a 2015 press release. In 2016, ZTE began centralizing video surveillance for the government around the country, according to current and former employees.

In its final push for the fatherland cards, the government no longer considered RFID, according to people familiar with the effort. The location-tracking technology was too costly.

Instead, it asked ZTE for help with QR codes, the black-and-white squares smartphone users can scan to get directed to web sites. ZTE developed the codes, at a cost of less than $3 per account, and the government printed the cards, linking them to the Soltein database, these people said.

In a phone call with Reuters in September, Su, the head of ZTE’s Venezuela business, confirmed the company’s card deal with Cantv. He declined to answer follow-up questions.

Maduro introduced the cards in December 2016. In a televised address, he held one up, thanked China for lending unspecified support and said “everybody must get one.”

The ID system, still running on the Soltein platform, hadn’t yet migrated to ZTE servers. Disaster soon struck. In May 2017, hackers broke into the fatherland database.

The hack was carried out by anonymous anti-Maduro activists known as TeamHDP. The group’s leader, Twitter handle @YoSoyJustincito, said the hack was “extremely simple” and motivated by TeamHDP’s mission to expose Maduro secrets.

The hacker, who spoke to Reuters by text message, declined to be identified and said he is no longer in Venezuela. A Cantv manager who later helped migrate the database to ZTE servers confirmed details of the breach.

During the hack, TeamHDP took screenshots of user data and deleted the accounts of government officials, including Maduro. The president later appeared on television scanning his card and receiving an error message: “This person doesn’t exist.”

Screenshots of the information embedded in various card accounts, shared by TeamHDP with Reuters, included phone numbers, emails, home addresses, participation at Socialist Party events and even whether a person owns a pet. People familiar with the database said the screenshots appear authentic.

Shortly after the hack, Maduro signed a $70 million contract with Cantv and a state bank for “national security” projects. These included development of a “centralized fatherland database” and a mobile app to process payments, such as the discounted cost of a subsidized food box, associated with the card.

“Imperialist and unpatriotic factions have tried to harm the nation’s security,” the contract reads.

It says an undisclosed portion of the funding would come from the Venezuela China Joint Fund, a bilateral financing program. A related contract, also reviewed by Reuters, assigns the database and payment app projects to ZTE. The document doesn’t disclose how much of the $70 million would go to the Chinese company.

ZTE declined to comment on financial details of its business in Venezuela. Neither the Venezuelan nor the Chinese government responded to Reuters queries about the contracts.

In July 2017, Soltein transferred ownership of fatherland data to Cantv, project documents show. A team of a dozen ZTE developers began bolstering the database’s capacity and security, current and former Cantv employees said.

Among other measures, ZTE installed data storage units built by US-based Dell Technologies Inc, according to one ZTE document. Dell spokeswoman Lauren Lee said ZTE is a client in China but that Dell doesn’t sell equipment to ZTE in Venezuela. She said Dell reviewed its transactions in Venezuela and wasn’t aware of any sale to Cantv, either.

“Dell is committed to compliance with all applicable laws where we do business,” Lee said in an email. “We expect our customers, partners and suppliers to follow these same laws.”

In May, Venezuela held elections that were widely discredited by foreign governments after Maduro banned several opposition parties.

Ahead of the vote, ruling party officials urged voters to be “grateful” for government largesse dispensed via the fatherland cards. They set up “red point” kiosks near voting booths, where voters could scan their cards and register, Maduro himself promised, for a “fatherland prize.”

Those who scanned their cards later received a text message thanking them for supporting Maduro, according to several cardholders and one text message reviewed by Reuters. The prizes for voting, however, were never issued, cardholders and people familiar with the system said.

Current and former Cantv employees say the database registers if, but not how, a person voted. Still, some voters were led to believe the government would know. The belief is having a chilling effect.

One organizer of a food handout committee in the west-central city of Barinas said government managers had instructed her and colleagues to tell recipients their votes could be tracked. “We’ll find out if you voted for or against,” she said she told them.

State workers say they are a target.

An internal Cantv presentation from last year said the system can feed information from the database to ministries to help “generate statistics and take decisions.” After the vote, government offices including Banco Bicentenario del Pueblo, a state bank, sent Cantv lists with employees’ names to determine whether they had voted, according to the manager who helped set up the servers.

Banco Bicentenario didn’t respond to a request for comment. Officials at the Economy Ministry, which the bank reports to, didn’t respond to requests, either.

With personal data now so available, some citizens fear they can lose more than just their jobs, said Mariela Magallanes, an opposition lawmaker who headed a commission that last year investigated how the fatherland card was being linked to the subsidized food program.

The government, the commission said in a report, is depriving some citizens of the food boxes because they don’t possess the card. “The government knows exactly who is most vulnerable to pressure,” she said.

(By Angus Berwick. Additional reporting by Adam Jourdan in Shanghai, Ben Blanchard in Beijing, Eric Auchard in London, Sarah Marsh in Havana, Ivan Alonso in Cancun, Christine Murray in Mexico City, Francisco Aguilar in Barinas, and Andreina Aponte in Caracas; Editing by Paulo Prada)

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?