Former detainees tell New Mexico legislators about abuses in immigration detention as county seeks to renew contracts

Joselin Mendez, 28, told New Mexico state legislators about being held in solitary confinement while detained at the Cibola County Correctional Center. She was among many former detainees who asked lawmakers to prevent contract renewals with private prison companies and the federal government at a hearing on July 16, 2018 at the Capitol in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

At New Mexico’s state capitol Monday, state legislators heard, for the first time, testimony from people who have been detained inside the two for-profit immigration detention centers in the state. What they heard were memories of trauma and allegations of abuse — and calls to end privately-run detention in New Mexico for good.

“We ask you to put yourselves in the shoes of our communities,” said 37-year-old Hilaria Martínez, who told lawmakers through an interpreter that her husband was recently locked up in immigrant detention for 50 days. She says he still still suffers from the trauma of the experience, as do her children.

The hearing put New Mexico state legislators in unchartered territory, because they had never made a state-level push to change local Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations.

Few states have taken broad action. California signed a package of sanctuary bills into law in 2017 that limit how local law enforcement resources may aid in immigration enforcement, empower the state’s Attorney General to review the conditions of immigrant detention and bar counties from entering into new contracts with ICE.

At the hearing in New Mexico, immigrants and advocates filled a room of roughly 200 people where members of the Courts, Corrections and Justice committee, which convened the hearing, raised many broad ideas, including reviewing contractors’ licenses to do business in New Mexico, passing legislation similar to California’s and simply requiring greater transparency. Throughout, a sprinkling of legislators called for the “abolition of ICE” and the decriminalization of immigration. At the hearing, Matt Baca, senior counsel for the New Mexico attorney general, said his office is considering prosecuting individual cases of criminal negligence and abuse at detention facilities.

Meanwhile, the deadline to terminate or renew the ICE agreement for the Otero County ICE Processing Center in southern New Mexico is approaching in November. The facility is operated by the private prison company Management and Training Corporation (MTC) through a deal made directly with the county government. Under New Mexico statute, all agreements with private prison contractors must be approved by the Office of the Attorney General.

When asked how the office woud vet the proposed renewal in light of detainees’ testimony, spokesperson David Carl said it would be inappropriate for the office to comment before it receives the proposed agreement. In October 2016, attorney general’s office approved a contract with a private prison company to detain immigrants at the Cibola County Correctional Center. That contract will last until 2021. County commissioners said then that the deal would provide much needed jobs.

But those who spoke at the hearing urged lawmakers to find other ways to create jobs.

“We urge you to not renew contracts with these institutions and to work on economic alternatives,” said Hilaria Martínez. “New Mexico can serve as a model for the rest of the nation — if our legislature takes a stand against private detention and prisons.”

Three recent detainees also testified at the hearing about “inhumane” conditions at the Otero facility; they said they were denied sufficient food, access to sunlight and to medical staff by guards who were abusive. The Department of Homeland Security’s Inspector General’s office made a surprise visit to Otero in 2017 and found evidence of the unjustified use of solitary confinement, unsanitary conditions and non-working telephones.

“They treated us like animals, like cows at a dairy,” said Roberto de Jesus Gonzalez, a longtime New Mexico resident and father of three who says he was arrested by ICE at his local courthouse — like Martínez’s husband — before being detained for three months at Otero.

Otero County Manager Pamela Heltner told PRI by email that Otero County will “most likely” renew its contract with ICE come November. The county subcontracts with MTC to operate the facility. She said that the county is currently awaiting a draft renewal agreement. Heltner did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the testimony Otero detainees gave at the hearing.

Immigration attorney Allegra Love founded the Santa Fe Dreamers Project, which offers free legal services to trans women detainees at the Cibola County Correctional Center. She says the county should be able to end its contract without controversy.

A 2014 government study of the “alternatives to detention” program, in which immigrants are released from detention pending court dates, found that 99 percent of detainees with GPS tracking devices (such as ankle monitors, or telephone check-ins) showed up to their court hearings.

More about alternatives to detention.

Love says rather than detaining immigrants, “all of these people can be absorbed into community and then they can show up at their court hearing and they can either win or lose their asylum case.”

“It’s not a radical idea,” she said. “It’s completely radical that we would detain people who have no criminal issues [when] we can easily control their movement.”

A recently released detainee from Cibola, 28-year-old Joselin Mendez, testified at the hearing. She told lawmakers through an interpreter that she was placed in solitary confinement and felt that she was treated like a criminal, though she was a non-criminal detainee.

“I feel nervous, but also empowered,” she told PRI before the hearing, “knowing that I’m here to speak not just for myself but for other trans women.”

During the hearing, Mendez talked about 33-year-old Roxsana Hernandez, who died of HIV-related complications in May soon after being transferred to Cibola. The detention center is owned and operated by private prison giant CoreCivic, formerly called Corrections Corporation of America, which has an enterprise value of $4.2 billion.

Hernandez’s death is one of eight which have occurred in ICE custody since the beginning of 2018, according to an analysis of ICE press releases by the American Immigration Lawyers Association. Half of those detainees were locked up in facilities run by CoreCivic.

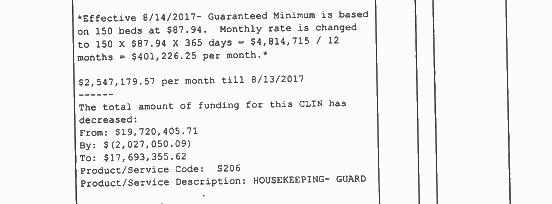

Medical neglect at the prison has previously proven deadly. In 2016, the Bureau of Prisons cancelled its contract with CoreCivic to hold federal prisoners at Cibola, after federal monitors attributed multiple deaths there to deficient care. But CoreCivic soon landed a new partnership with ICE and the county government, under a secret, five-year-deal that circumvented the federal bidding process through a structure in which ICE pays Cibola County and Cibola County pays CoreCivic. The government initially agreed to pay CoreCivic $150 million for the first five years.

The National Immigration Justice Center, which advocates for immigrants, calls Cibola “a black hole of due process.” And, after Cibola County officials overspent $5.6 million of ICE funds meant for CoreCivic, the contract was amended in March 2018, according to the county manager. The amendment, obtained by PRI, shows the contract was reduced. CoreCivic was initially receiving $2.5 million per month for detaining up to 847 people per day; they now get just over $400,000 for a minimum of 150 detainees, though when the detainee population reaches 848, ICE pays an additional $55 per detainee per day.

Both CoreCivic and MTC declined invitations from state legislators to speak at the hearing. Spokespeople for each corporation told PRI that they declined out of deference to the federal government. They also each pledged their commitment to oversight, saying that the companies work closely with on-site monitors employed by ICE.

Ronald Vitiello, ICE’s acting director, was also invited to speak but did not attend the meeting.

“I find it very disrespectful that a body like ours would be so grossly ignored by the agency that is responsible for carrying this disastrous policy forward,” said Rep. Javier Martinez.

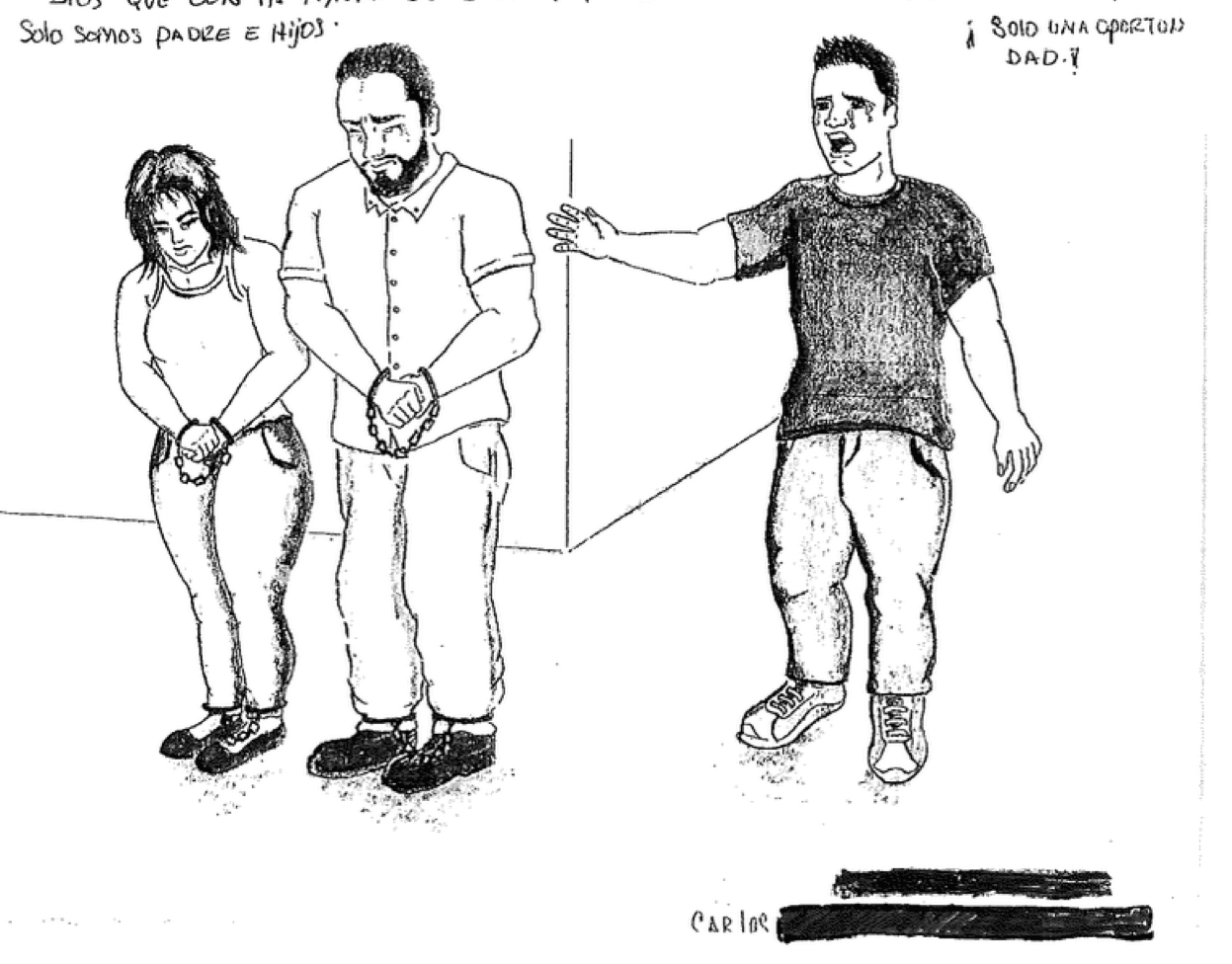

During the hearing, Martinez also commented on a set of handwritten letters from fathers held at Cibola who were separated from their children at the border. The letters were submitted to the committee by attorney Adriel D. Orozco of the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center. He has represented detainees at both the Otero and Cibola detention centers.

“Our state has the opportunity to join other states and localities to prevent the federal government from using New Mexico to further its irrational and inhumane immigration policies,” Orozco said.

“These stories vindicate the idea that ICE has outlived its purpose,” Martinez said. “We really should be talking about abolishing ICE and reimagining what immigration enforcement will look like in the future.”

Like all states except California, New Mexico has no legislation to bar county governments and law enforcement agencies from entering or renewing contracts with ICE. But several city and county governments in Texas, Oregon and California have given up the financial gains of partnering with ICE, even when they are not formally barred by state governments from doing so.

For community organizer Maria de Jesus Martinez, it boils down to whether or not local officials’ care about the human cost of for-profit immigrant detention.

“When these private corporations make so much money, it means that there are many families that are separated and sad and that feel anxiety over not knowing how to reunite with their family,” she told lawmakers. “We don’t want them to make more money from our bodies. They’re treating us like merchandise.”

Sara MacNeil contributed to this report.