Liberia was founded by people enslaved in the US. Advocates say the US should not end an immigration program that helps them.

Elouise Stevens, 19, rallied in St. Paul, Minnesota on March 26, 2018 in support of the renewal of Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) for Liberians. It's an immigration program that has allowed her mother to stay in the US for 18 years. Stevens says it's hard to speak out, but that it gives them hope.

Louise Stevens works two jobs to pay the mortgage and put her daughter Elouise, a DACA recipient, through college in Minneapolis. She didn’t expect that her own immigration status is what would cause the most doubt for their future.

Stevens has Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), a program created in the Clinton administration to shelter Liberians in the US from their country’s ruinous civil war. Only about 4,000 Liberians are in the program; it does not apply to any other country. About 745 people have authorization to work with DED, according to the Congressional Research Service.

After 18 years of renewals by presidents both Republican and Democratic, the program was set expire on March 31. The White House said Tuesday that it would end the program in one year, giving Liberians here with DED until March 31, 2019 to adjust their status or leave the country lest they become undocumented. An official with the Department of Homeland Security told the Star Tribune in Minneapolis, “It’s up to Congress now to come up with a permanent fix.”

If Liberians leave the US, Minnesota, home to the largest community of Liberians in the country, will lose crucial workers. The state depends on many of them to fill essential health care positions. A state report found that 10 percent of Minnesota’s labor pool is foreign-born, and health care workers like Stevens are already in short supply.

One of Stevens’ jobs is as a caregiver at an adult care center. “The jobs that I’ve had for all these years, I would have no more,” she says. “I really don’t know what to do, to be honest. I really, really don’t know.”

Her other occupation is on the assembly line of a medical technology company.

When Stevens came to the US 18 years ago, her daughter Elouise was 2 years old. The war had destroyed their life in Liberia. Now she works and owns a home in Brooklyn Park, a suburb of Minneapolis that is popular among Liberians. If President Donald Trump takes no action, Stevens, 59, will be undocumented on April 1 and possibly subject to deportation.

“I came to America with one suitcase,” she says. “I moved in this house on April 1, 2006. It will be exactly 12 years that I’ve been paying the mortgage and keeping my house.”

If she is deported or loses her job, she doesn’t think she would be able to keep the house or build up her savings again. Meanwhile, Minnesota’s health care industry is concerned about losing vital workers.

“We depend on Liberian immigrants quite a lot,” says John Doughty via email. He’s the administrator of the Camilia Rose Care Center, a nursing home in Coon Rapids, north of Minneapolis. Doughty employs four nurses, seven trained medication aides and 18 certified nursing assistants, all from Liberia. Those 29 people account for 15 percent of his medical personnel.

If Liberians were to lose their DED status, the impact on his ability to operate the facility and offer quality care would be significant, he says. Staffing agencies not only don’t have enough people to send, but they’re also so expensive that using them would more than double the costs of lost labor, he says.

Other managers of care facilities agree.

“It would be devastating to our organization,” says Kristina Roegires, a human resources director at Mary T. Inc., a multi-state elder-care organization based in Minneapolis. The company relies heavily on African immigrants, including many from Liberia. It simply can’t afford to spare “even a portion” of them, she says in an email.

Dr. Bruce Corrie, an economist who studies immigrants’ footprint on the economy as director of Planning and Economic Development in Saint Paul, says that while the number of Liberian immigrants in Minnesota is small — under 10,000 people according to census data — they have a “significant impact.” 78.6 percent of Liberian immigrants are in the labor force, and more than 26 percent of them work in medical care.

“Right now there’s a very tight job market in Minnesota, particularly in the [Twin Cities] metro area,” says Roegires. There aren’t enough people to provide nursing home or other forms of direct care as it is. Losing employees could force organizations to reduce service, not a good thing with the state’s “rapidly aging Baby Boomer generation that will need more of these types of facilities, not less,” she says.

Corrie agrees that elderly people in nursing homes would be hit the hardest. He says Liberians “are doing some very tough work that ordinary Americans don’t want to do. That’s why new immigrants fill that role in a niche area.”

DED exists at the sole discretion of the president in his power to shape foreign relations, and this administration has already canceled other forms of immigration assistance. Trump has attempted to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the fiercely fought-over program that shelters from deportation immigrants who arrived as children, as well as Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for several countries, which allows foreign nationals to be legally in the US while their countries recover from conflict or natural disaster.

“There’s a deep sense of fear,” says Wynfred Russell, co-founder of ACER, a nonprofit organization in Minneapolis that advocates for Liberians in the US. “Previous administrations have typically renewed the DED, on average, two months prior.”

Even if Liberians aren’t immediately targeted for deportation come April, they don’t want lives where they are vulnerable to deportation because of traffic stops or other encounters with law enforcement, he says.

Also: Black and Muslim, some African immigrants feel the brunt of Trump’s immigration plans

Some, like Stevens, have lived under the DED designation for decades, while others acquired it in 2007 when President George W. Bush reinstated the program. When Liberia had another civil war in 2002, its refugees were given TPS and then transitioned to DED.

Much like the DACA program, DED has no pathway to citizenship, only periodic extensions, usually 18 months at a time. For the Stevenses, who face the double uncertainty of DED and DACA, the cloud hanging over their heads has only gotten darker.

“To be somewhere for 18 years and to not know if you’ll be here next year is very hard,” says 19-year-old Elouise Stevens. “Especially if you’ve been away from your home for such a long time. It’s very scary.”

Years ago, she was granted asylum under her father’s application. He was deported in 2011 following a criminal conviction, so she too lost her lawful status, she says. In June 2017 she gained immigration relief with DACA, a status she’ll have until 2019. She studies at Minneapolis Community and Technical College.

“We’ve been displaced and because of the situation we’re in, we’re forced to put ourselves in these categories of DED and DACA,” she says. Elouise would like to attend a four-year college to study architecture, but is not sure what to do without any immigration security.

“I’m just going through life day by day, making sure that I take everything to the fullest and trying to make sure that I have a good day, instead of having a good year,” she says. She focuses on her grades, one of the things she can control. “I try to keep up as much as possible to have stability.”

“These folks [Liberians] came through the legal process,” says Russell. They “paid taxes, have been contributing to the economy.” The economist, Corrie, estimates using census data that Liberians in Minnesota earned $167 million in income in 2015, while the nearly 60,000 Liberians nationwide earned $1 billion.

Liberians in the US have reached out to the Department of Homeland Security for answers, says Russell, “because the president will definitely rely on guidance from department.” But they never got a reply.

PRI reached out to the Homeland Security to inquire about the likelihood of an extension as well, but the agency did not reply.

Opal Tometi, the executive director of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, a national social-justice organization, calls the situation “unconscionable.” “Close to 4,000 Liberians, some of whom have been here for 30 years might become undocumented. Families and communities will be torn apart if DED isn’t renewed by March 31,” she says. However, Trump, she says, has a poor record. “The administration’s systemic attacks on black immigrants shows that his immigration agenda is steeped in xenophobia and racism.”

“As a union, we will continue to fight,” says Jamie Gulley, the president of Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Healthcare Minnesota, in an email statement to PRI. “Caring for people is more than just a job for our Liberian members. It is a huge part of their lives and every day they improve the lives of tens of thousands of Minnesotans.”

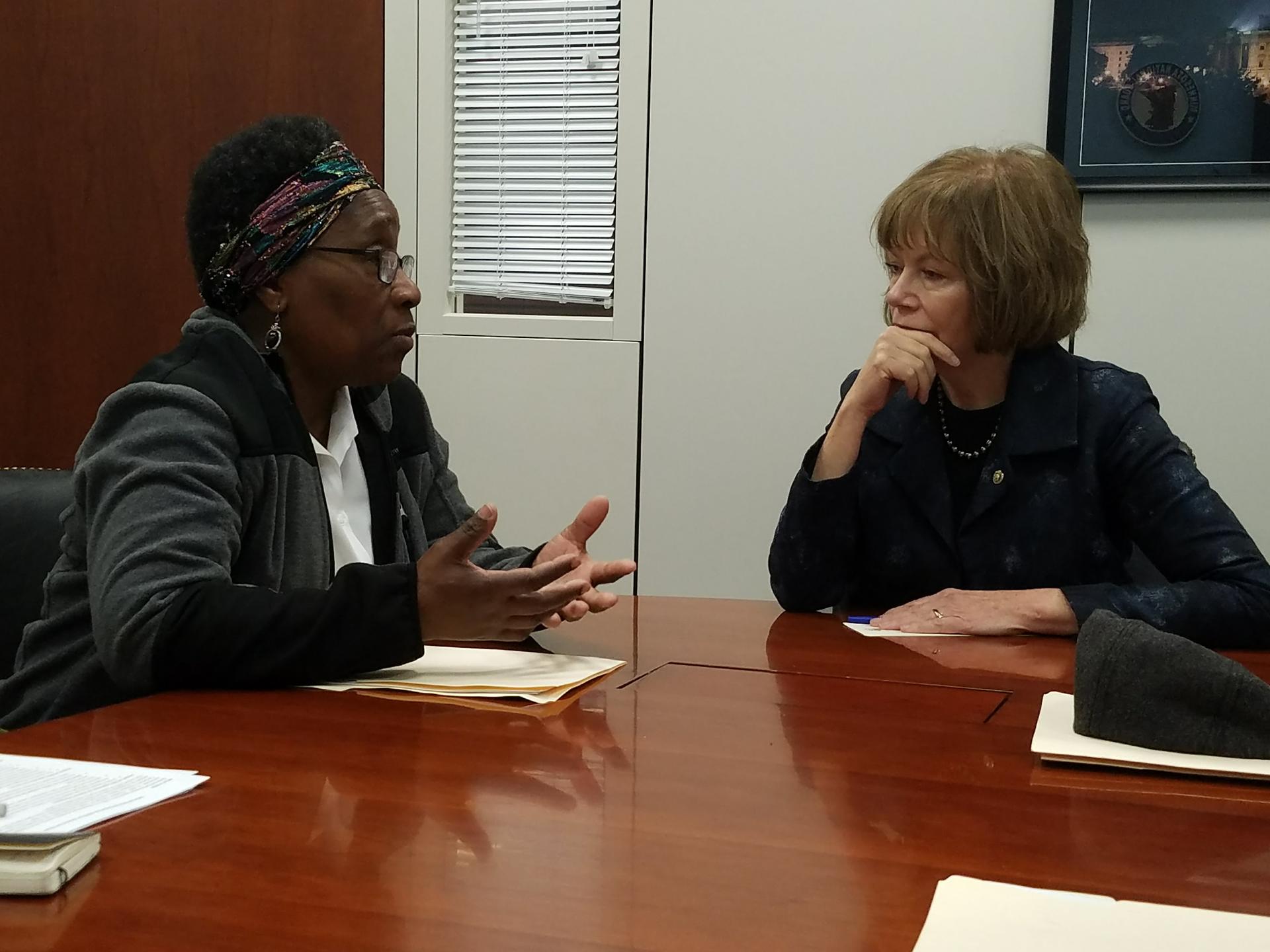

The union, which has over 35,000 health care workers across the state, along with faith groups and immigration advocates, is helping Liberians to lobby Congress. Their goal is to get a 3-year extension, or at least another 18 months, to give people time to organize their lives. Both Louise and Elouise Stevens went to Washington, DC, to participate in the effort, which they say gave them hope.

“When you explain these things, there are also emotions that come along,” says Elouise. “Basically, seeing my mom essentially beg these people to push this agenda was extremely hard.”

In February, Minnesota Rep. Keith Ellison introduced legislation that would give eligible Liberians the chance to become legal permanent residents, so they can stay regardless of temporary programs. He’s also been collecting signatures on a letter to Trump about the foreign policy implications of DED. Assisting in the “reemergence of Liberia,” ensuring “regional stability,” and helping “foster Liberia’s continuing post-war recovery,” were among them.

Royce Bernstein Murray, policy director at the advocacy group American Immigration Council, says that many people will view the end of DED as an indication that Liberia’s relationship to the US has weakened in this administration. The county’s fragile economy with “high rates of unemployment and inadequate basic services” would be strained by thousands of returning expatriates, she says in an email, while the country would lose millions of dollars in remittances.

Supporters of Liberian DED holders rallied at the Minnesota state capitol in St. Paul on Monday morning in an effort to make their situation more visible.

“Some of the Liberians who are here have ancestors’ roots in this country itself,” says Corrie. Freed people who were slaves in the US founded Liberia, initially as a US colony, to escape persecution. “We have to understand the historical context.“

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3Dpg48G4qBdlo

Ira Melhman, the media director of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), an organization that advocates for limiting immigration to the US, thinks that foreign policy has nothing to do with DED. “Its purpose is humanitarian,” he says via email. “The fact that Liberia has a long history with the United States should not weigh in the consideration of whether to terminate a status that is no longer justified by circumstance, and hasn’t been for quite some time.”

Such programs only defer the requirement to leave, they don’t waive it, he says. The fact that these temporary programs are still active after so many years means that they “have been abused and that abuse needs to end.”

Louise Stevens prays that the administration will continue the relief, and perhaps one day, there might be a path to citizenship for DED holders.

“Since America was gracious to open her door to us, let America be gracious to say, ‘This is the end.’ But at least give us time.”

Now she has one more year.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect the White House memorandum issued on March 27, 2018, the day after the story was first published.