Is taekwondo the key to peace between North and South Korea?

Members of North Korea-led International Taekwondo Federation demonstrate their skills at the World Taekwondo Headquarters, also known as Kukkiwon, in Seoul, South Korea.

With just a month to go before the start of the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics in South Korea, there’s still no decision from North Korea if it will send its athletes to the games.

After months of giving South Korea the cold shoulder, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un said in his New Year's speech that he was willing to send a delegation to the 2018 Olympics in the south.

On Tuesday, President Moon Jae-in of South Korea responded by saying "I appreciate and welcome the North’s positive response to our proposal that the Pyeongchang Olympics should be used as a turning point in improving South-North relations and promoting peace."

There’s hope that Pyongyang’s participation would help foster dialogue and lower tensions that have risen since the Kim Jong-un regime’s ICBM test in November, which prompted condemnation from the United Nations Security Council. The North describes strengthened UN sanctions as an “act of war.”

Related: North Korea claims nuclear statehood with US in missile range

Sports diplomacy between the two Koreas was hailed as a breakthrough as recently as last June. That’s when Pyongyang sent a taekwondo demonstration team to a competition in Muju, South Korea.

The 16 athletes showed off roundhouse kicks and smashed through boards and bricks. All the while, South Korean spectators cheered them on.

“I thought this was a sign of improving relations between our countries,” says Oh Hye-ri, a South Korean Olympic gold medalist in taekwondo. “I really welcomed them here.”

Taekwondo is a Korean martial art, but athletes from the South and North don’t compete against each other because they belong to different leagues that are affiliated with their respective nations.

While there is virtually no dialogue between the South and North Korean governments and militaries, the heads of these taekwondo associations send letters and emails or call each other on the phone.

“Sports can open dialogue between the North and South,” says Choue Chung-won, the Seoul-based president of World Taekwondo.

He says during the North Korean team’s weeklong stay in South Korea the two sides had a lot to talk about, though discussions about politics were best avoided.

Related: South Korea proposes high-level talks with North

Before heading back home, the visiting delegation invited South Korean athletes to Pyongyang to perform during an International Taekwondo Federation (ITF) tournament in September.

For Choue, 70, the chance to visit North Korea is something he’s always thought about. He is the son of North Korean refugees who escaped their homeland shortly after the Korean peninsula was divided at the end of World War II.

“We have relatives there, but we don’t have any communication between us,” Choue says, noting that millions of other South Koreans belong to similar separated families.

Kim Seong-ju hasn’t seen his family in the North since he defected to South Korea in 2003. The 34-year-old athlete is the first North Korean refugee to graduate from the Korea National Sports University in Seoul with a degree in taekwondo.

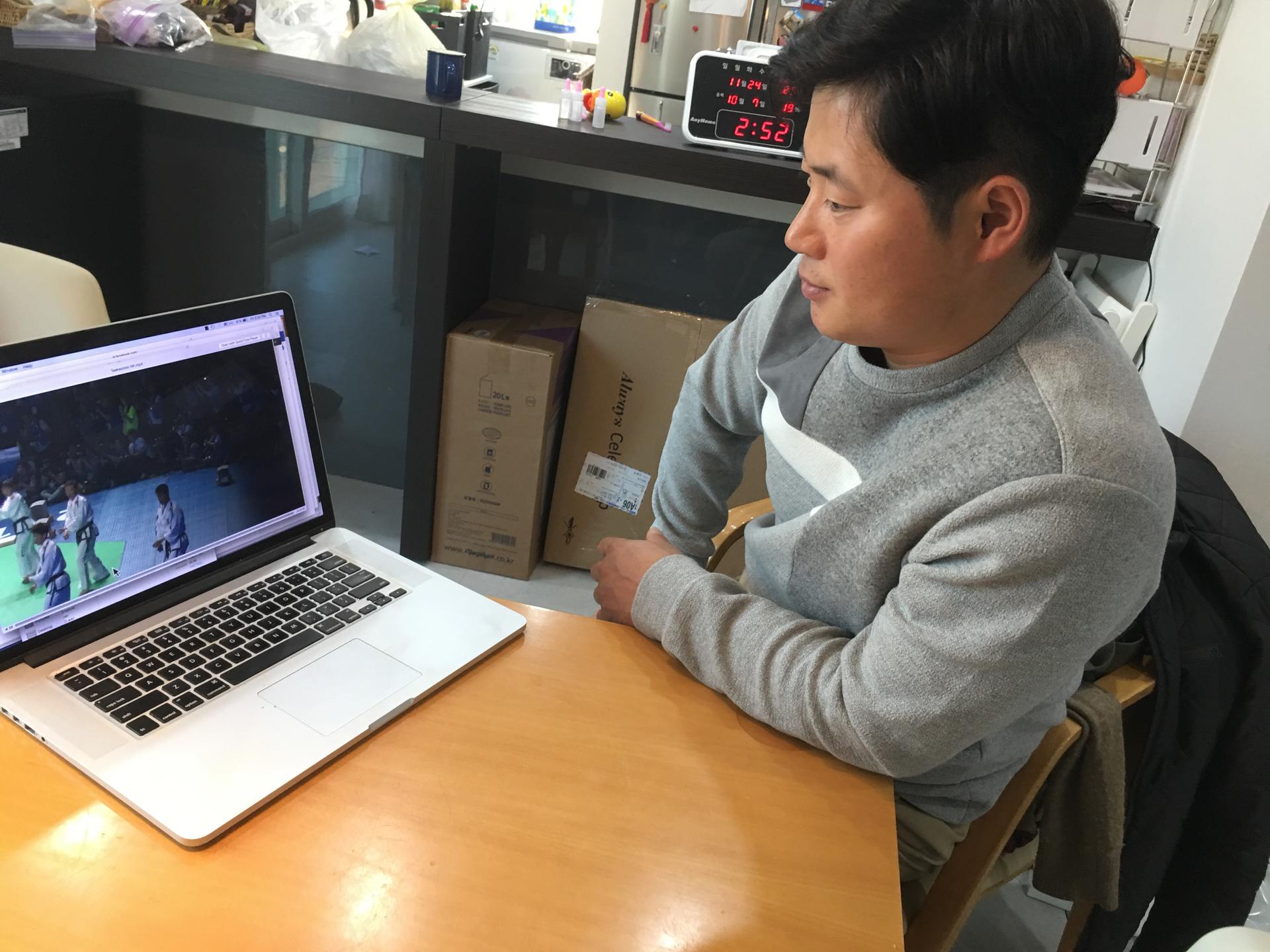

Watching a video of the North Korean athletes’ June performance in Muju, Kim says he’s encouraged by these kinds of cultural exchanges between the two countries.

Sports is a “great step forward” for inter-Korean relations, Kim says, adding that he hopes South Korean athletes will soon be able to make a reciprocal visit.

But a trip to North Korea might not come any time soon. Ahead of the ITF competition in September, Pyongyang rescinded its invitation to the South Korean taekwondo team.

World Taekwondo’s Choue Chung-won says all that his North Korean counterparts told him in a letter was that the situation at that time was not conducive to the visit.

“I’ll accept their excuse as it is,” Choue says.

Choue hasn’t lost hope in taekwondo diplomacy — he’s invited the North Korean team back to South Korea to perform on the sidelines of the Winter Olympics.

Given the North Korean leader’s comments that he’s considering sending a delegation to the Pyeongchang games, that just might happen.

Jason Strother reported from South Korea.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?