Scientists warn we may be creating a ‘digital dark age’

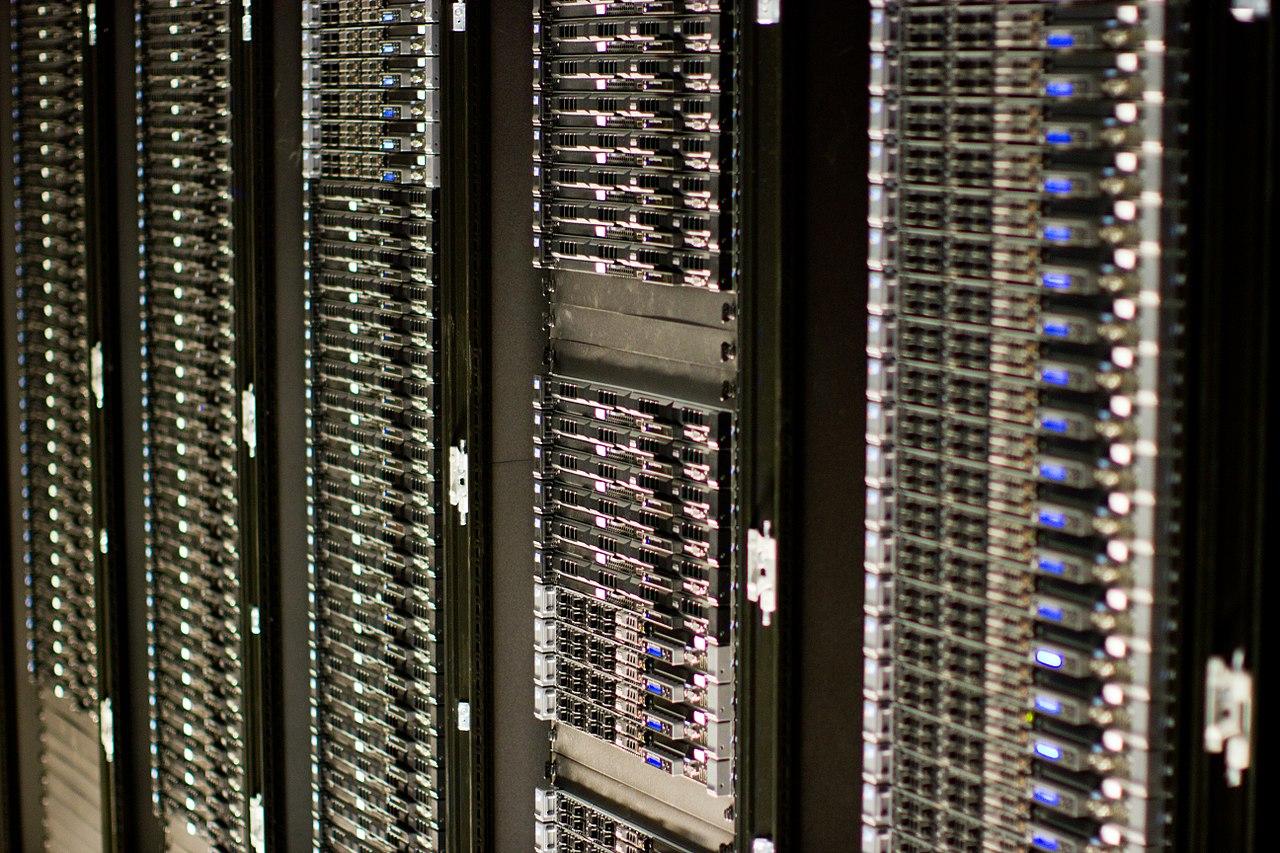

Wikimedia Foundation servers

You may think that those photos on Facebook or all your tweets may last forever, or might even come back to haunt you, depending on what you have out there. But, in reality, much of our digital information is at risk of disappearing in the future.

Unlike in previous decades, no physical record exists these days for much of the digital material we own. Your old CDs, for example, will not last more than a couple of decades. This worries archivists and archaeologists and presents a knotty technological challenge.

“We may [one day] know less about the early 21st century than we do about the early 20th century,” says Rick West, who manages data at Google. “The early 20th century is still largely based on things like paper and film formats that are still accessible to a large extent; whereas, much of what we're doing now — the things we're putting into the cloud, our digital content — is born digital. It's not something that we translated from an analog container into a digital container, but, in fact, it is born, and now increasingly dies, as digital content, without any kind of analog counterpart.”

Computer and data specialists refer to this era of lost data as the "digital dark ages." Other experts call the 21st century an “informational black hole,” because the digital information we are creating right now may not be readable by machines and software programs of the future. All that data, they worry — our century’s digital history — is at risk of never being recoverable.

Surprisingly, many of the world’s largest companies and data-based enterprises still rely on an old storage medium: magnetic tape. In 1952, IBM introduced the first magnetic tape data storage system, ushering in the modern era of electronic computing. An early tape unit could hold about 2.3 megabytes per reel on two tapes.

The medium has come a long way, says Lauren Young, Science Friday's web producer and the lead reporter on a three-part series called "File Not Found," which explores issues of data storage (and loss) of all kinds. A single cartridge of today’s magnetic tape can hold hundreds of terabytes of data, the equivalent to hundreds of millions of books, Young says. “This past summer, IBM increased the amount a cartridge can hold to 330 terabytes, which is 330,000 gigabytes per cartridge. Big companies like Google and particle physics labs like Fermilab all have massive libraries of tape with thousands and thousands of cartridges.”

While most companies use digital technologies for first-line storage, in many cases, magnetic tape is the backup to the backup. This, too, can present problems, in the form of evolving magnetic formats and a phenomenon known as "bit rot." Over time, the digital information on tape, and in other digital formats, can decay or degrade if it is not stored properly or is subjected to other adverse conditions.

Kari Kraus, an associate professor in the College of Information Studies at the University of Maryland in College Park and who helps run a project that rescues and resurrects digital relics, including video games and virtual worlds, knows about bit rot, and its close relative "software rot," in which old files, games and other data becomes unusable because no format exists to read and reproduce the information.

“Different storage media have different lifespans,” Kraus says. “In our project, we worked a lot with magnetic media like floppy disks and those only have a lifespan of, say, 10 to 14 years. Optical media like DVDs and CD-ROM, I believe have even less. It is going to be a problem across different storage media.”

Lauren Young says some researchers see hope in one of the newest technologies: DNA storage. “Basically, researchers have found a way to store data onto DNA, which is a billion-year-old molecule that can store the essence of life,” Young explains. “It's pretty incredible that they can do that. It's all synthetically made; it’s not genomic DNA.”

In this case, storage capacity is measured in petabytes; that is, millions of gigabytes. Science Magazine writes: “A single gram of DNA could, in principle, store every bit of datum ever recorded by humans in a container about the size and weight of a couple of pickup trucks.”

Kari Kraus understands the urgency but says she cannot make up her mind whether the phrase, digital dark ages, is overblown or not. “We have architectural ruins; we have paintings in tatters. The past always survives in fragments already,” she says. “I guess I tend to see preservation as not a binary — either it's preserved or it's not. There are gradations of preservation. We can often preserve parts of a larger whole.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.