Scientists are keeping a close eye on the Beaufort Gyre

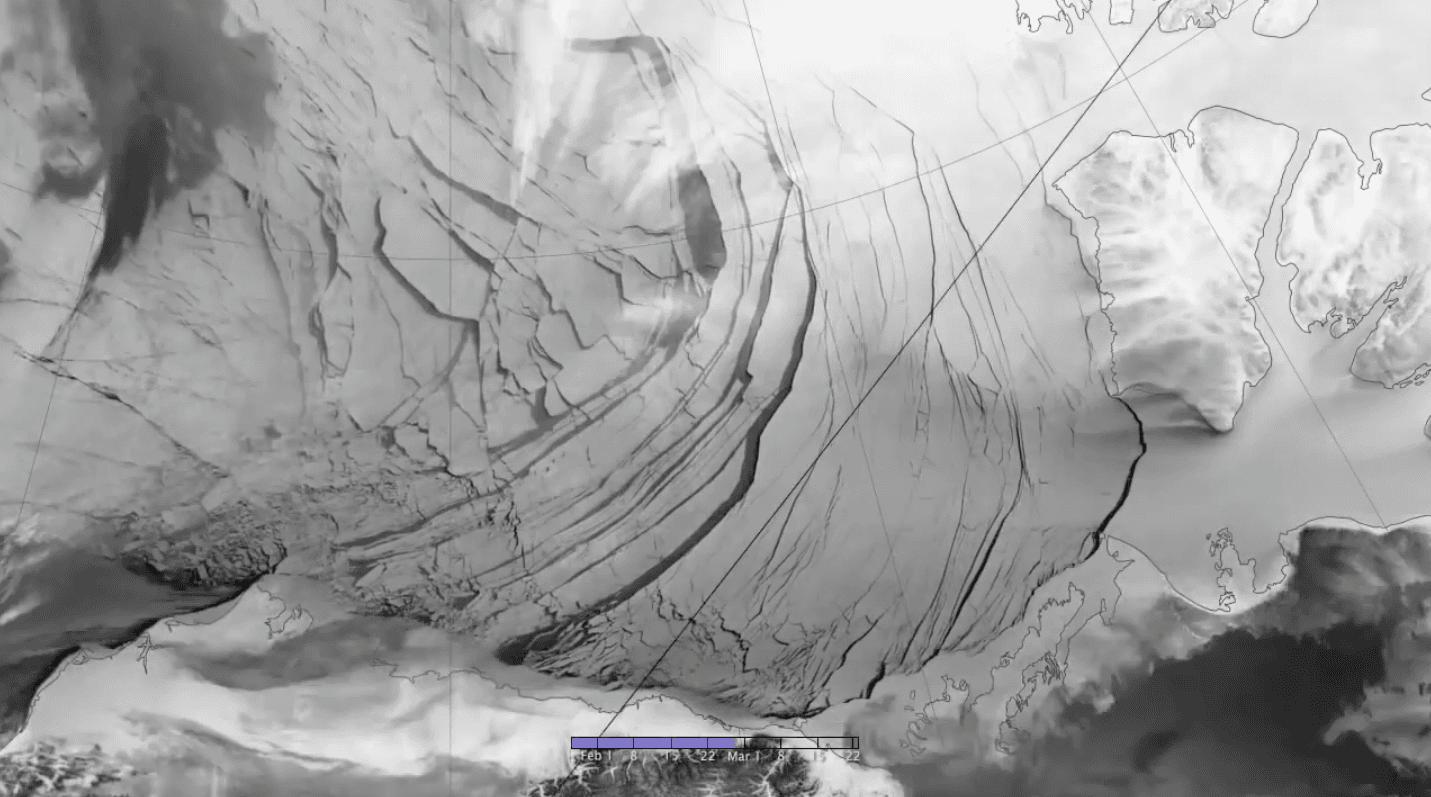

Ice cracks in the Beaufort Sea, driven by the Beaufort Gyre.

The Beaufort Gyre, an immense 60-mile-diameter pool of cold freshwater and sea ice, is “stuck” in a clockwise rotation that should have ended years ago. Its eventual reversal could send massive amounts of chilly water straight toward western Europe, plunging it into brutal winters and disrupting fisheries.

The gyre spins in the Beaufort Sea, north of Alaska and Canada and south of the North Pole. When this ocean current spins clockwise, it traps Arctic ice and freshwater melt. When it spins the other way, it ejects that ice and freshwater out past Greenland into the North Atlantic, making weather in Northern Europe cooler. It is a natural phenomenon, but something has gone awry with the way it operates, as its periodic reversal is way overdue.

Typically, cyclonic storms occur every five to seven years in the North Atlantic and move into the Arctic, causing the gyre to weaken and reverse direction, explains journalist Ed Struzik, a fellow with the Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen's University and author of “Future Arctic: Field Notes from a World on the Edge.” In recent years, however, the Arctic has been warming faster than the rest of the planet, and scientists speculate this has caused the gyre to stay in a clockwise direction for more than a dozen years.

“Nobody really understands what's going on,” Struzik says, “but it's probably a combination of climate change and massive runoff of freshwater coming off the Greenland glacier that is preventing those big cyclones from forming over the North Atlantic and moving into the Arctic.”

So the gyre just keeps getting bigger, spinning faster and collecting more water, Struzik says. “Imagine all of the water that we have in the Great Lakes — that’s the amount of freshwater trapped in the Arctic just waiting to get out.”

Scientists are waiting with bated breath, he says. They see signals that the gyre could reverse sooner rather than later, but they thought this was the case in 2013 and it turned out not to be. When it does happen, Struzik says, we won’t see a "The Day After Tomorrow" scenario, in which the world goes into a deep freeze, but it's definitely going to “create some problems" for the European countries near the North Atlantic. The last time this happened, in the 1960s and 1970s, western Europe endured eight of its most severe winters and the surge of ice and freshwater disrupted the North Atlantic food chain; this, in turn, caused a collapse of the lucrative herring fishery.

Hypothetically, a quickly warming Arctic and its effect on the gyre could impact weather across North America, as well. Warming Arctic waters appear to be disrupting the flow of the jet stream, creating a kind of “loopiness” in its shape that tends to hold weather patterns in place, Struzik explains. This can bring Arctic air further south than usual and create unusual extreme weather events, like what recently occurred in Corpus Christi, Texas, which received several inches of snow a few weeks ago.

“I think that's likely what's happening and we're going to see more of that in the future,” Struzik says. “But then again, we really don't know, because this is sort of an emerging science that everybody's trying to study and everybody's figuring out.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.