Miami residents fear ‘climate gentrification’ as investors seek higher ground

Women walk past a mural in the Little Haiti neighborhood in Miami, May 17, 2017.

Schiller Sanon-Jules remembers eating fried pork and plantains in Little Haiti when he was a kid in the 1980s.

“It was a taste of Haiti,” says Sanon-Jules, who immigrated to the US as a child and now owns the Little Haiti Thrift and Gift Store, one of the shops on the neighborhood’s brightly-colored main street.

As a teenager, he used to parade down the same street with friends and drums, in a kind of Haitian second line.

Related: In Miami’s Little Haiti, one of the largest waves of evictions is currently underway

“Every Saturday night, this is where you’d find us,” says Sanon-Jules. “Sometimes we’d be out for two or three hours just walking, and there’d be like 100 people following the band.”

But the neighborhood is changing, gentrifying rapidly. As developers buy up property and push out longtime residents, Sanon-Jules says “you don’t have the Haitian influx that you used to have.”

Little Haiti’s location, close to both the beach and downtown, makes it a prime target for development. But some residents also believe there’s another factor contributing to gentrification here: the threat of climate change.

Beachfront flooding makes higher ground more attractive

On Miami’s beachfront, rising seas regularly push water up through the ground during high tides. Flooding is more and more of a problem. But Little Haiti sits roughly a mile inland, and on relatively high ground. Sanon-Jules’ store, for example, is 11 feet above sea level — nearly double the average elevation of Miami.

Some residents believe that relatively high elevation makes their neighborhood a more attractive investment for developers.

“For sure, I think that 100 percent,” says resident Lidia Toussaint, who grew up in the neighborhood.

After Hurricane Irma made rivers out of roads in some Miami neighborhoods in September, Toussaint noticed Little Haiti was relatively dry.

“This area, we didn’t really experience flooding. We really just got some downed power lines,” says Toussaint.

“I was having this conversation with a friend about how this changes the market in this area, makes it more valuable. So now we’re definitely going to get pushed out of here.”

Toussaint believes that’s already happening. Her parents have lived here for nearly 40 years. But as their rent rises, they’re looking at moving somewhere cheaper.

“They’re retired, so their income is restricted,” Toussaint says. “They can’t afford it, so now they’re going to have to try to find something they can afford.”

Is climate gentrification really happening?

The term “climate gentrification” bubbled up a few years ago and has gained traction mostly among activists and journalists who wonder if it’s really happening.

Valencia Gunder, a powerhouse activist who lives in Liberty City, one neighborhood inland from Little Haiti, believes it is.

“What we’re seeing is Little Haiti is going to be completely wiped out in the next, maybe, five to 10 years,” says Gunder. Three new developments are being proposed in the area, and Gunder thinks part of the reason why is that developers are wary of investing in beachfront property.

It’s a historical reversal here, and it’s pushing new development into communities where immigrants and people of color have traditionally lived.

“In Miami, historically, because of racism, red-lining and segregation, all of the brown and black people were forced to live in the center of the city, which also happens to be the high elevated areas,” Gunder explains. “So, they pushed us here because they didn’t want us on the beach.”

But now, the future doesn’t look so good on the beach. Rising seas could put most of south Florida’s coastal areas under water by the end of the century.

New research shows that nationwide, homes at risk of sea level rise are starting to lose value.

Researchers from the University of Colorado at Boulder and Penn State University used Zillow home sales data to determine that nationwide, coastal homes that would be inundated with six feet of sea level rise sold, on average, for 7 percent less than similar homes equidistant to the coast that were not at risk from sea level rise. This effect was even more pronounced for homes that would flood with one foot of sea level rise, which sold for 22 percent less on average than similar properties.

In Miami, there’s anecdotal evidence that frequent flooding is impacting individual renter’s choices too.

“I live on the second floor on my apartment block, and that’s a conscious decision,” says Charles Bradley, who lives in flood-prone South Beach.

“You just see puddles appearing, and it can be like the hottest day in July, and you know it’s not come from the sky, it’s coming out of the ground,” says Bradley, who’s been stuck at home before because he can’t get his car through flooded streets.

Real estate hot all over Miami, not just on high ground

But despite these worries about flooding, waterfront property is still being rapidly developed.

Brickell, the neighborhood just south of downtown Miami on Biscayne Bay, experienced massive flooding during Hurricane Irma in September. But its real estate market is still booming. Cranes building new condo towers dot the horizon, and the population has nearly tripled since 2000.

“The City of Miami has a very hot real estate market throughout the whole city,” says Jane Gilbert, the city’s chief resilience officer.

So are activists and residents wrong about the impact of rising seas?

Harvard’s Jesse Keenan has been looking at price appreciation rates in Miami to answer that question, and he says the answer is complicated.

“Across Miami-Dade County, the higher elevation you are, the faster the rate of price appreciation, across the entire county,” says Keenan.

Keenan does believe recurrent flooding is slowing appreciation in some small patches of Miami. But by and large, his research does not find that sea level rise risk is what’s driving gentrification.

“We actually think that’s probably natural land-pricing pressures that come from good old-fashioned gentrification,” Keenan says.

Miami’s low-lying beachfront land is expensive, and the Everglades provides a boundary for expansion to the city’s west, so new development is naturally moving inland and upward.

But Keenan says that doesn’t mean activists worried about climate gentrification are totally wrong. He’s had conversations with foreign institutional investors and local, multi-generational developers in Miami who say climate change is influencing their investment decisions.

“If [climate gentrification] is not happening now, it’s going to happen,” says Keenan. “Ten years, 15 years, who knows? But it’s going to happen much sooner than later.”

Keenan says the important question is how Miami will ensure access to affordable housing if people start to flee the beach and crowd into inland communities.

Jane Gilbert, Miami’s chief resilience officer, says the city isn’t looking at climate gentrification per se. The current priority, about a year into her tenure as the city’s first resilience officer, is to figure out how to fortify the coastline.

“We’ve got a huge amount of built-out infrastructure along our coast. It’s some of our most valuable real estate,” she says.

Her team is looking at what kinds of infrastructure changes Miami needs to keep residents in their coastal homes through 2060, in the face of something like two to three feet of sea level rise.

“We feel that we can probably manage that without significant migration away from our coast,” says Gilbert.

She says her resilience team is considering ways to increase affordable housing citywide, from incentivizing mixed-income development along new rapid-transit lines in Miami to getting owners of affordable housing complexes to make flood-resistant upgrades.

“Housing affordability in general is a major concern,” she says.

But a focus on high-elevation areas prone to the emerging trend of climate gentrification will come later, she explains.

“Right now it’s often hard for cities to plan beyond election cycles, so we’re trying to work beyond the 20 to 40 year cycle, which is its own level of challenge,” Gilbert says. “To plan out to 2100 is not something cities usually do.”

Nationwide, inland cities will need to start planning for sea level rise too

By that date, it’s possible people won’t just be moving a few blocks inland.

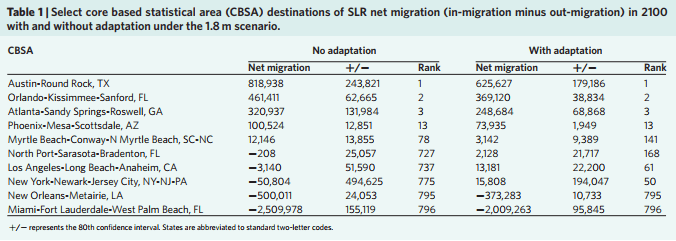

An analysis published in the journal Nature in April found more than 2.5 million people might move out of the greater Miami area by the end of the century if sea level rises roughly six feet — which could well happen. The paper’s author Matt Hauer estimates as many as 13.1 million people nationwide could be at risk of migrating if no adaptation measures are taken.

“We’re looking at a migration that would be of a similar magnitude as the Great Migration,” Hauer says.

If that’s the case, climate gentrification may not be Little Haiti’s problem at all, but Orlando’s — or Austin’s. According to Hauer’s analysis of migration patterns dating back to 1990, those two cities would be the top destinations for people leaving coastal areas and could gain nearly 1.3 million residents by 2100.

The bottom line, he says: sea level rise is not just a coastal issue.

“If we don’t start thinking now about incorporating these migration flows into long term strategic planning, we have the serious potential of being woefully unprepared for what the future’s going to hold,” Hauer says.

For Little Haiti businessman Schiller Sanon-Jules, gentrification has already taken its toll.

He’s closing his Haitian gift shop at the end of the month because the landlord nearly doubled the rent.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?