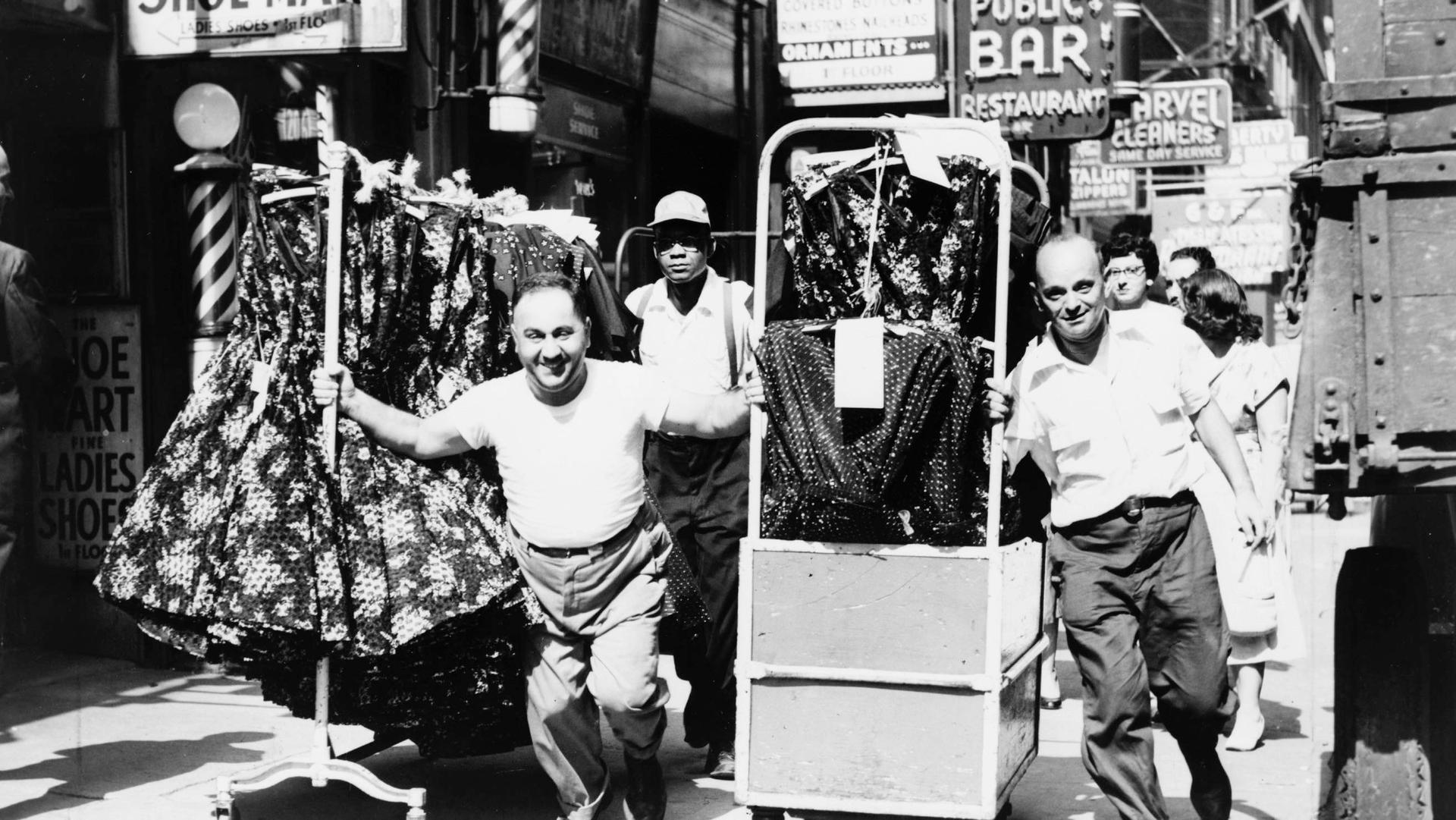

Men pull racks of clothing on a busy sidewalk in New York City's Garment District.

My lineage is wrapped up in the garment industry. My grandfather on my dad’s side was in the garment business. My aunties on my mom’s side were also in the industry.

My dad was a doctor, and when I was 6, my family moved from the center of the garment industry, New York City, to North Carolina, America's garment manufacturing state. The first time I got an inkling as to what the clothing industry was all about was when my little sister Claudia took a sewing class at the Singer store at the mall in Raleigh. I joined her on an outing to buy material at a fabric outlet store.

They sold leftovers of bolt cloth, surplus from the nearby factories. The second we walked in the door, our noses and lungs were seized by the camphor and other unknown odors wafting off mountains of cloth along the long aisles. I left Claudia inside to continue scrounging for material. She didn't waste much time.

This is part an Across Women's Lives project: Wear and Tear series: The women who make our clothes.

That smell gave me a visceral understanding of the industry, and I would recognize it over the coming years when I’d visit sweatshops in Mumbai or the “dead yovo” used clothing markets of West Africa.

My own family’s history in America’s garment industry traces the evolution of its growth and flight from these shores.

My grandfather, Morris Werman, arrived at Ellis Island as a 16-year-old in the late 1800s. He’d already apprenticed as a tailor in Krakow, Poland. He saw the conditions in the New York City sweatshops and, according to my cousin Lynn Goldman, whose memory of conversations with Grandpa is sharp, he was horrified by what he saw. He was an early member of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), which, despite its name, also had strong membership among male immigrants in the business.

Grandpa would have clearly remembered the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 that killed 146 seamstresses, half of whom were young Jewish women emigrés.

“He got totally fed up working for ‘the bosses,’” Lynn wrote me recently. “He always used to refer to ‘the bosses’ in the most scathing way. He said there was unbelievable exploitation.” What Grandpa likely meant by that was — in the absence of labor laws — the absurdly low rates seamstresses were paid per garment. A report in an 1892 edition of The Century cites 50 cents as a typical wage for a 17-hour day.

So, Grandpa went into business for himself. “He had a knack for doing knockoffs,” Lynn recalls. “He would stroll past the windows of Bonwit Teller and Saks. He would memorize the designs,” and then design a similar coat out of luxurious fabrics.

But if distancing himself from the clutches of the powerful sweatshop infrastructure was his goal, it seems my grandfather succeeded, but then caved.

He found that the most reliable buyers of his designs were manufacturers who made inexpensive coats in bulk (reminding me of Morty Seinfeld’s immortal quote from “Seinfeld,” that you move merchandise with “cheap fabric and dim lighting”). But they always requested changes to the designs: Make the pockets smaller or narrow the collar to use less fabric. “Then,” Lynn said, “they would take Grandpa’s patterns back to their sweatshops where they would make the coats of cheap fabrics, wool rather than cashmere, beaver rather than sable.”

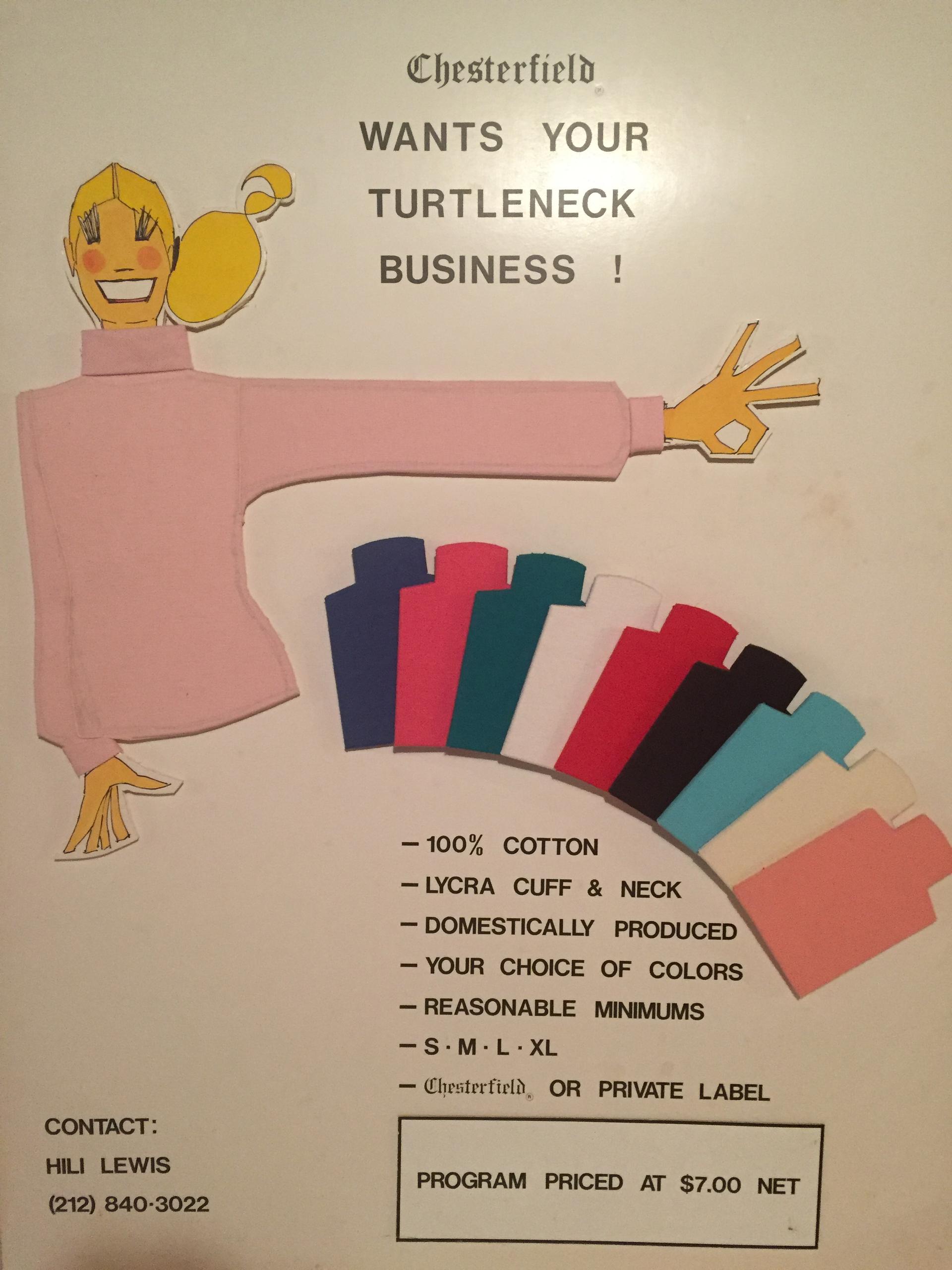

A generation later, on my mom’s side of the family, my aunt, Hili Lewis, was a young woman growing up in the midst of a New York fashion industry that was relying more on manufacturing outside the city — in other states. New York was transforming itself — Seventh Avenue especially — to more of a design, brand and marketing center. Her father, Mac Lewis, ran Esquire Sportswear for 35 years and showed Hili the ropes. At the time, those early ropes didn’t exactly spell out “fast fashion.”

“Life in the clothing business in Father's time,” Aunt Hili wrote me, “was built on trust and the formation of personal relationships. Customers from out of town stayed in our house when they came to New York for market weeks and buying trips, and became ‘family,’ so much so that I called them all ‘uncles’ as a kid.”

There were no women, she told me, in upper management positions in those days, but that was history by the time Hili and Aunt Mir together created Chesterfield, a thriving ready-to-wear brand of sportswear that they marketed in department stores across the country.

Fast fashion would catch up with them, though. I visited them in the summer of 1992 when I was covering the Democratic National Convention in New York City. Their manufacturer in South Carolina could no longer afford to stay in business, and they had to liquidate their company.

Mir and Hili both told me, in a joint message, “it was terribly painful to watch the shift take place so quickly. The effect it had on American manufacturers was devastating and unstoppable because it was suddenly impossible to compete with pricing overseas.”

Hili still has the best jokes about people who work in the garment business. But they’re mostly frozen in the '50s and '60s, when numbers-crunching, New York "garmentos" worried about moving inventory could still be distilled to a funny punchline. Today, how do you make a joke about “fast fashion”?

As for Morris Werman, it was his daughter — whom I know as Aunt Lucille — who ended up with many of his cast-off samples, the good stuff. So, as my cousin Lynn told me, Aunt Lucille “was always well dressed.”

Lynn still has one of those samples. An off-white wool coat with a fur collar. “Incredible detail and generous cuffs,” noted Lynn when she sent me the pictures.

It is gorgeous. But less so when you think about its life as a sweatshop knockoff.