After Cassini, where to next?

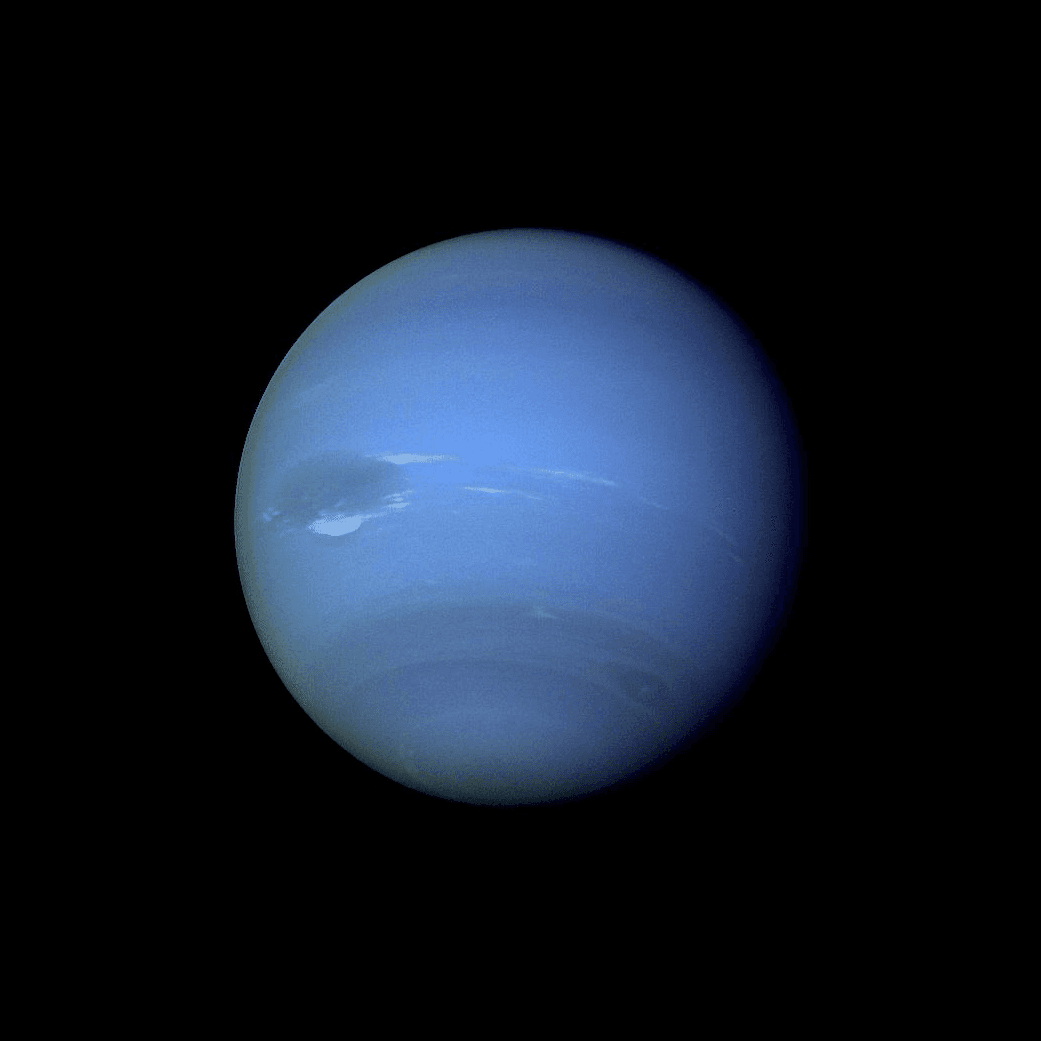

Neptune, as seen by Voyager 2. Astronomers think that it may be raining diamonds inside the atmospheres of Neptune and Uranus.

The Cassini spacecraft just ended its 13-year orbit around Saturn in September, and scientists are already dreaming of where to send the next orbiter.

Two potential destinations? Neptune and Uranus. Known as the “ice giants” of our solar system, both planets are hard to study from Earth because of their distance — and they seem to have some seriously wild weather. Case in point: Astronomers think that inside the planets’ atmospheres, it’s raining diamonds.

“In the early 90s, it was realized that these two planets … were fundamentally different,” says Tim Dowling, a professor of planetary physics at the University of Louisville. “And what's different about them is their mantles. Between the core and the outer atmosphere, it is not hydrogen and helium — in fact, it's water, methane and ammonia. So that's the ice, that's where the name [“ice giant”] comes from.”

Scientists have long suspected that under extreme pressure, the methane on these ice giants could be crushed into diamonds, Dowling explains. “Now, this idea actually was confirmed this summer at Stanford,” he says. “They had a couple of lasers hit polystyrene, which is just eight Cs and eight Hs, and that's very much like methane, and darned if all the carbon didn't turn into diamond.”

However, Dowling says any jeweled “ice” on Neptune or Uranus would be hard to spot, even if we do send an orbiter to get a closer look. “You'd have to go about halfway in,” he explains. And in spite of their names, the interiors of the ice giants are actually really, really hot: “So not only are you talking real bling here, it's bathed in a golden light just like the sun — so it would be amazing to be able to see it.”

Bling aside, there are other reasons why scientists might get excited about a NASA mission to Neptune or Uranus. For one, we might be able to learn a thing or two about our own planet. Dowling says that weather on planets like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune can be predicted months ahead of time, not weeks like on Earth.

“We very much need to learn about Earth,” he says. “But Earth doesn't come with a user manual, so we have to write our own, right? So you want to go to the other planets for that.” And while missions like Juno and Cassini have given us up-close looks at Jupiter and Saturn, our peeks at Uranus and Neptune have been fleeting — Voyager 2 flew past both in the 1980s.

The final price tag for the Cassini mission to Saturn was $3.9 billion, and Dowling says sending an orbiter to the ice giants would undoubtedly be expensive as well.

“But I think what Cassini showed us is that if you do put the kitchen sink in, and you go all-in, that you have incredible flexibility and you have a 13-year mission that was originally a five-year mission,” he says. “It was just fantastic. They made it. They did everything with Cassini. That's what we need to send to Uranus or Neptune.”

This article is based on an interview from Science Friday‘s recent live show at the Brown Theater in Louisville, Kentucky