With papers, my brother-in-law could be worth more than a dollar a day to the world

Visa-seekers stand outside the US Consulate in Ciudad Juarez in 2010.

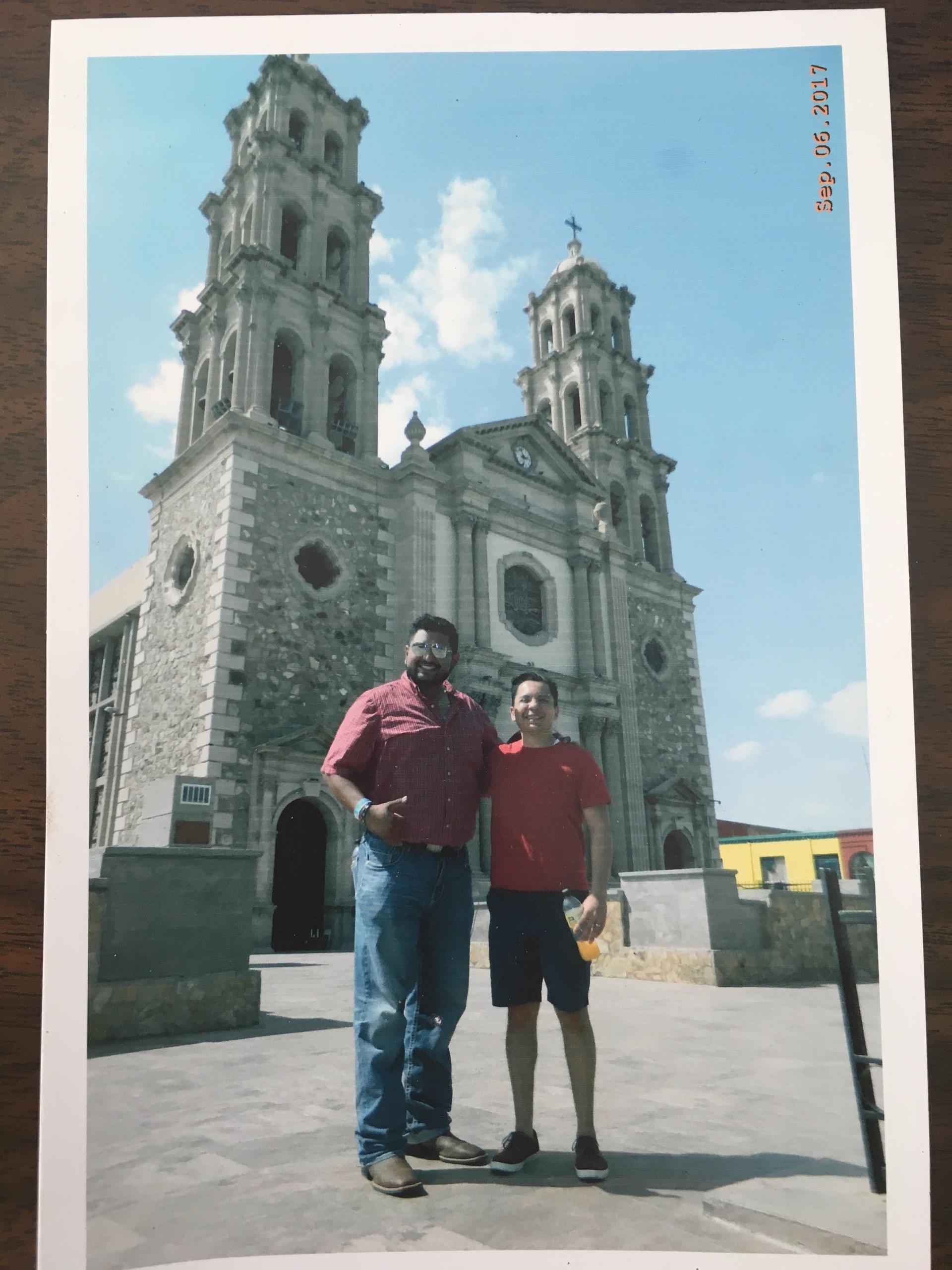

Outside, the heat was finally tired of beating on the suburbs. Sore and spent, it let the evening go. My brother-in-law and I were seated at the dinner table in a tiny vacation rental, going at a plate of grocery store fried chicken and a two-liter bottle of Country Time lemonade. It had been a quiet couple of days in El Paso, Texas, waiting to cross into Ciudad Juárez the next morning for his visa interview.

“Mano, esta es tu última cena de mojado,” I said. Bro, this is your last meal as a wetback.

Antonio Ramirez let out a hearty laugh, his eyes twinkling.

“Yeah, man! Maybe it’s my last dinner here ever!”

We both laughed harder than we meant to. Antonio to tamp down his mounting anxiety, and me to pretend there wasn’t any truth to what he’d said.

He first crossed the border — on foot and without permission — when he was a teenager, full of big dreams and perfect plans. He seldom talks about it, like a war veteran or a victim of abuse, but a few years ago he wrote down some of his thoughts and shared them with me. I remember reading them and being surprised that he saw US Border Patrol agents as the good guys.

“Dude, it’s true,” Antonio said. “If they catch you, they’ll give you a bottle of water and a ride back to Mexico. I actually turned myself into them more than once. I didn’t wanna die.”

On his first of several crossing attempts, he said, he wanted to ditch his sweater as the day wore on and the heat became oppressive. It felt like extra weight. But his guide persuaded him otherwise, and he was glad he listened. He got through the cold that night with his sweater.

That first crossing and the one we’re making in the morning are connected, like call and answer phrases in a field song. Fear binds them together, stifling our awkward laughter, turning our dinner mournful and our conversations terse. I can sense this fear brewing inside him, threatening rain, but I can’t say I know how it feels.

I came to the US from Guatemala when I was 9, on a plane. The pilot gave me a little winged pin and a peek at the cockpit. My mom took me to the tail of the plane and showed me the desert far below, splotches of yellow and red. I took a nap, and when I woke up we were in San Francisco.

More by David Lindes: 2,800 miles and 26 years later, a new dad looks for his own father in Guatemala

Antonio married my older sister, a US citizen, in the spring of 2007. On the brink of the Great Recession at the beginning of 2008, the company he worked for in Salt Lake City folded and he was laid off from his job as a cabinet maker. I had just graduated from college and landed a job in the tech industry. Many of my fellow graduates struggled to find work — a few of them for years — and I struggled with a bad case of survivor’s guilt.

Not Antonio. The very day he was driving home after being laid off, he called his former boss.

“Hey! Do you have plans for the delivery truck?”

“No man, I won’t be using it anymore.”

“Can I borrow it?”

He rounded up a few of his newly-unemployed friends, created a classified ad online selling moving services and got to work. When our families had dinner together a few weeks later, he told me he’d made more money moving people than he had making cabinets. Even without documents, Antonio could work miracles to provide for himself and his family, and I’ve always admired him for it. But I could always tell he knew his status was slowing him down.

It hurt me as well to watch him be villainized in an increasingly toxic campaign against illegal immigration. At the time he was laid off, I had a number of conservative colleagues at work, and they’d often engage in conversations that were offensive to me as a Hispanic man and an immigrant.

“Yeah, David, but you’re not like them, you’re not illegal, you’re different. You’re law-abiding, you’re all about your family, you’re an example.”

I corrected my colleague with as much simplicity and tact as I could muster by telling him about Antonio.

The night before his visa interview in Ciudad Juárez, we chatted over pan dulce and hot chocolate to try and ease Antonio’s nerves. At 11 p.m. he was still sitting up in his hotel bed, rifling through documents. I drifted off to sleep, still in denial, thinking he was stressing out over nothing.

The next morning, as I waited outside the consulate, I realized I forgot my watch. All I had to tell the time were the slowly migrating shadows, shrinking to hide from the sun, like dogs under a disapproving owner’s glare. And there, between the elevated crosswalk and the consulate entrance, leaning up against fences and storefronts, sitting on dirty steps, mothers, friends, wives, husbands, partners, kids, even grandparents, made our waiting room. We tried our best not to look up every few seconds, in anticipation of answers.

I was 7 when “Roberto el Colocho” (Robert the Curly One), a neighbor just a couple of years older than me, told me, “En los Estados Unidos, tiran televisiones que todavía funcionan.” In the United States, they throw away perfectly good televisions.

“¿Por qué?” I asked. Why?

“Porque se compraron una más grande, una nueva.” Because they bought a bigger one, a new one.

“¡Púchica, mano!” Dang, man!

In the US, Ninja Turtle action figures were just $5. I knew from watching “The Wonder Years” that kids had their own cars. That they attended schools with hallways and lockers, that their homes were humongous and surrounded by green grass and perpetual barbecues.

And there, sitting on the stoop of Roberto El Colocho’s house in working class Guatemala City, where tiny concrete homes seemed to huddle together for warmth and protection and old green buses roared like gray, spent lions, with smell of diesel and green mangoes with lemon and salt, I began to think of the US as a kind of glorious afterlife.

But at the consulate, ojados, ilegales, indocumentados were being transformed — through a ceremony of questions, papers and stamps — into permanent residents. When they went in the door, they were “people that have lots of problems.” They were “bringing drugs,” they were “bringing crime,” they were “rapists.” When their weight on the chair made the first sound, a creak of plastic and metal, they were worth a dollar a day to the world.

In minutes, though, through the miraculous power of bureaucracy, they could be worth at least $22,000 per year for a family of four. They could be “legal,” with the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness on US soil. They could become “law abiding, all about their families, an “example” as my former co-worker had put it. They could be part of the America that deserved to be put first.

Next to me, a man in his early 20s at most was speaking perfect English on the phone. “Mr. Phillips? Yeah, it’s me, Daniel. I just came out. No, no, they said our lawyer forgot to send an important document. They said we have to wait. I’m sure they’ll figure it out though. I’m hopeful.”

He laughed nervously.

I looked up and saw a chubby, middle-aged man with a mustache, dressed his very best, come out of the consulate beaming. His wife, a slight woman dressed with just as much care, smiled back and opened her arms as he approached. They hugged like pre-pubescent children, kissing awkwardly and smiling effusively in front of the convenience store. A dog barked a few feet away from them, and the man barked back, grinning, “¡Qué chulo el perrito ¿vaá?!” What a cute dog, right?

He had made it, and he knew that the events that had taken place in the last few hours would change their lives and the lives of their children forever.

But this couple was worth just as much before the mustachioed man’s interview, as after. And even though I hoped with all my strength that Antonio’s visa application would be approved, I was angry that it was even a question, that it mattered this much, that it had this much power over his life, over his future and the future of my sister and nieces. I was angry because I knew Antonio, and he was a great American before he went into the consulate.

A few weeks later, after spending a couple of weeks in Tampico with his mother and brothers, Antonio re-entered the US with a visa. That morning, from the Houston airport, he posted on Facebook: “Ya de regreso en mi tierra. :D” Back in my homeland again.

He called me a week or two after his return to US soil to say he received his green card in the mail. “Hasta los pinches ojos se me están poniendo azules!” he bragged on the phone. Even my damn eyes are turning blue!

Antonio will enroll in school next week and be eligible for financial aid. He’ll be applying for a new jobs as well, work authorization card in hand. I told him he could count on my support, that working and going to school would be tough, but worth it. He had a more ambitious point of view.

“A eso no le tengo miedo. Yo le tengo miedo a quedarme como estoy. Ya con papeles, sería una vergüenza.” I’m not afraid of that. I’m afraid of staying as I am. With papers, not changing would be shameful.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?