World hunger has increased for the first time in 15 years. Blame war and climate change.

Salem Abdullah Musabih, 6, lies on a bed at a malnutrition intensive care unit at a hospital in the Red Sea port city of Hodaida, Yemen, Sept. 11, 2016. Millions of Yemenis face food shortages and the threat of famine after more than two years of civil war.

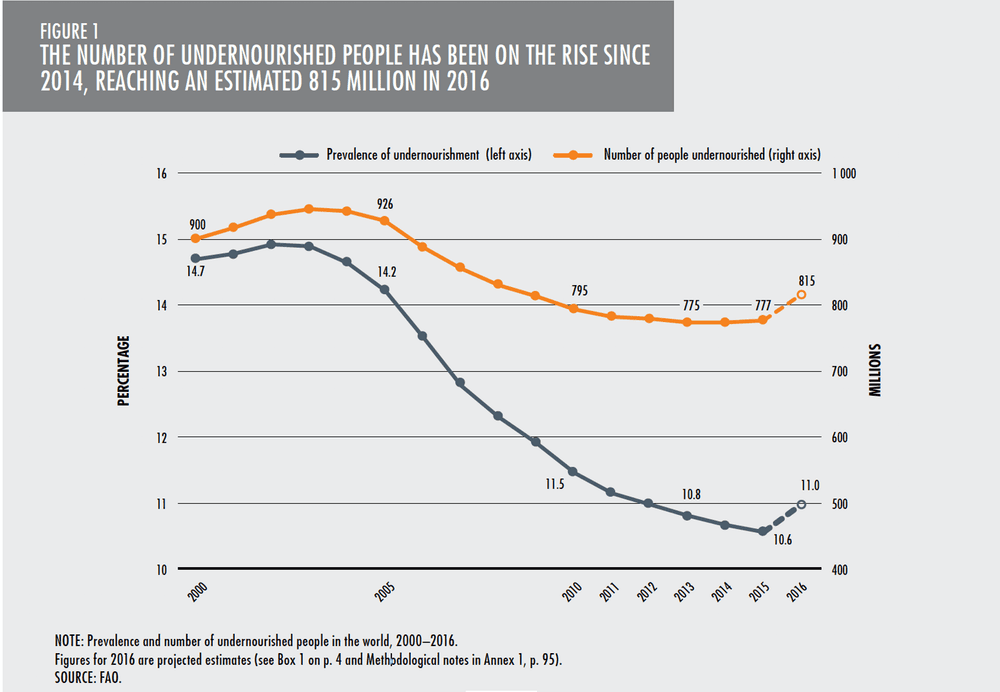

Around the globe, about 815 million people — 11 percent of the world’s population — went hungry in 2016, according to the latest data from the United Nations. This was the first increase in more than 15 years.

Between 1990 and 2015, due largely to a set of sweeping initiatives by the global community, the proportion of undernourished people in the world was cut in half. In 2015, UN member countries adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, which doubled down on this success by setting out to end hunger entirely by 2030. But a recent UN report shows that, after years of decline, hunger is on the rise again.

As evidenced by nonstop news coverage of floods, fires, refugees and violence, our planet has become a more unstable and less predictable place over the past few years. As these disasters compete for our attention, they make it harder for people in poor, marginalized and war-torn regions to access adequate food.

I study decisions that smallholder farmers and pastoralists, or livestock herders, make about their crops, animals and land. These choices are limited by lack of access to services, markets or credit; by poor governance or inappropriate policies; and by ethnic, gender and educational barriers. As a result, there is often little they can do to maintain secure or sustainable food production in the face of crises.

Related: Drought doesn't cause famine. People do.

The new UN report shows that to reduce and ultimately eliminate hunger, simply making agriculture more productive will not be enough. It also is essential to increase the options available to rural populations in an uncertain world.

Conflict and climate change threaten rural livelihoods

Around the world, social and political instability are on the rise. Since 2010, state-based conflict has increased by 60 percent and armed conflict within countries has increased by 125 percent. More than half of the food-insecure people identified in the UN report (489 million out of 815 million) live in countries with ongoing violence. More than three-quarters of the world’s chronically malnourished children (122 million of 155 million) live in conflict-affected regions.

At the same time, these regions are experiencing increasingly powerful storms, more frequent and persistent drought and more variable rainfall associated with global climate change. These trends are not unrelated. Conflict-torn communities are more vulnerable to climate-related disasters, and crop or livestock failure due to climate can contribute to social unrest.

War hits farmers especially hard. Conflict can evict them from their land, destroy crops and livestock, prevent them from acquiring seed and fertilizer or selling their produce, restrict their access to water and forage, and disrupt planting or harvest cycles. Many conflicts play out in rural areas characterized by smallholder agriculture or pastoralism. These small-scale farmers are some of the most vulnerable people on the planet. Supporting them is one of the UN's key strategies for reaching its food security targets.

Disrupted and displaced

Without other options to feed themselves, farmers and pastoralists in crisis may be forced to leave their land and communities. Migration is one of the most visible coping mechanisms for rural populations who face conflict or climate-related disasters.

Globally, the number of refugees and internally displaced persons doubled between 2007 and 2016. Of the estimated 64 million people who are currently displaced, more than 15 million are linked to one of the world’s most severe conflict-related food crises in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, South Sudan, Nigeria and Somalia.

Related: Ugandans pose as refugees for food because the drought is so bad

While migrating is uncertain and difficult, those with the fewest resources may not even have that option. New research by my colleagues at the University of Minnesota shows that the most vulnerable populations may be “trapped” in place, without the resources to migrate.

Displacement due to climate disasters also feeds conflict. Drought-induced migration in Syria, for example, has been linked to the conflict there, and many militants in Nigeria have been identified as farmers displaced by drought.

Supporting rural communities

To reduce world hunger in the long term, rural populations need sustainable ways to support themselves in the face of crisis. This means investing in strategies to support rural livelihoods that are resilient, diverse and interconnected.

Many large-scale food security initiatives supply farmers with improved crop and livestock varieties, plus fertilizer and other necessary inputs. This approach is crucial, but can lead farmers to focus most or all of their resources on growing more productive maize, wheat or rice. Specializing in this way increases risk. If farmers cannot plant seed on time or obtain fertilizers, or if rains fail, they have little to fall back on.

Increasingly, agricultural research and development agencies, NGOs and aid programs are working to help farmers maintain traditionally diverse farms by providing financial, agronomic and policy support for production and marketing of native crop and livestock species. Growing many different locally adapted crops provides for a range of nutritional needs and reduces farmers’ risk from variability in weather, inputs or timing.

Related: One-man NGO tries to save starving kids in Yemen

While investing in agriculture is viewed as the way forward in many developing regions, equally important is the ability of farmers to diversify their livelihood strategies beyond the farm. Income from off-farm employment can buffer farmers against crop failure or livestock loss, and is a key component of food security for many agricultural households.

Training, education, and literacy programs allow rural people to access a greater range of income and information sources. This is especially true for women, who are often more vulnerable to food insecurity than men.

Conflict also tears apart rural communities, breaking down traditional social structures. These networks and relationships facilitate exchanges of information, goods and services, help protect natural resources, and provide insurance and buffering mechanisms.

In many places, one of the best ways to bolster food security is by helping farmers connect to both traditional and innovative social networks, through which they can pool resources, store food, seed and inputs and make investments. Mobile phones enable farmers to get information on weather and market prices, work cooperatively with other producers and buyers and obtain aid, agricultural extension or veterinary services. Leveraging multiple forms of connectivity is a central strategy for supporting resilient livelihoods.

In the past two decades the world has come together to fight hunger. This effort has produced innovations in agriculture, technology and knowledge transfer. Now, however, the compounding crises of violent conflict and a changing climate show that this approach is not enough. In the planet’s most vulnerable places, food security depends not just on making agriculture more productive, but also on making rural livelihoods diverse, interconnected and adaptable.

This story was first published by The Conversation.