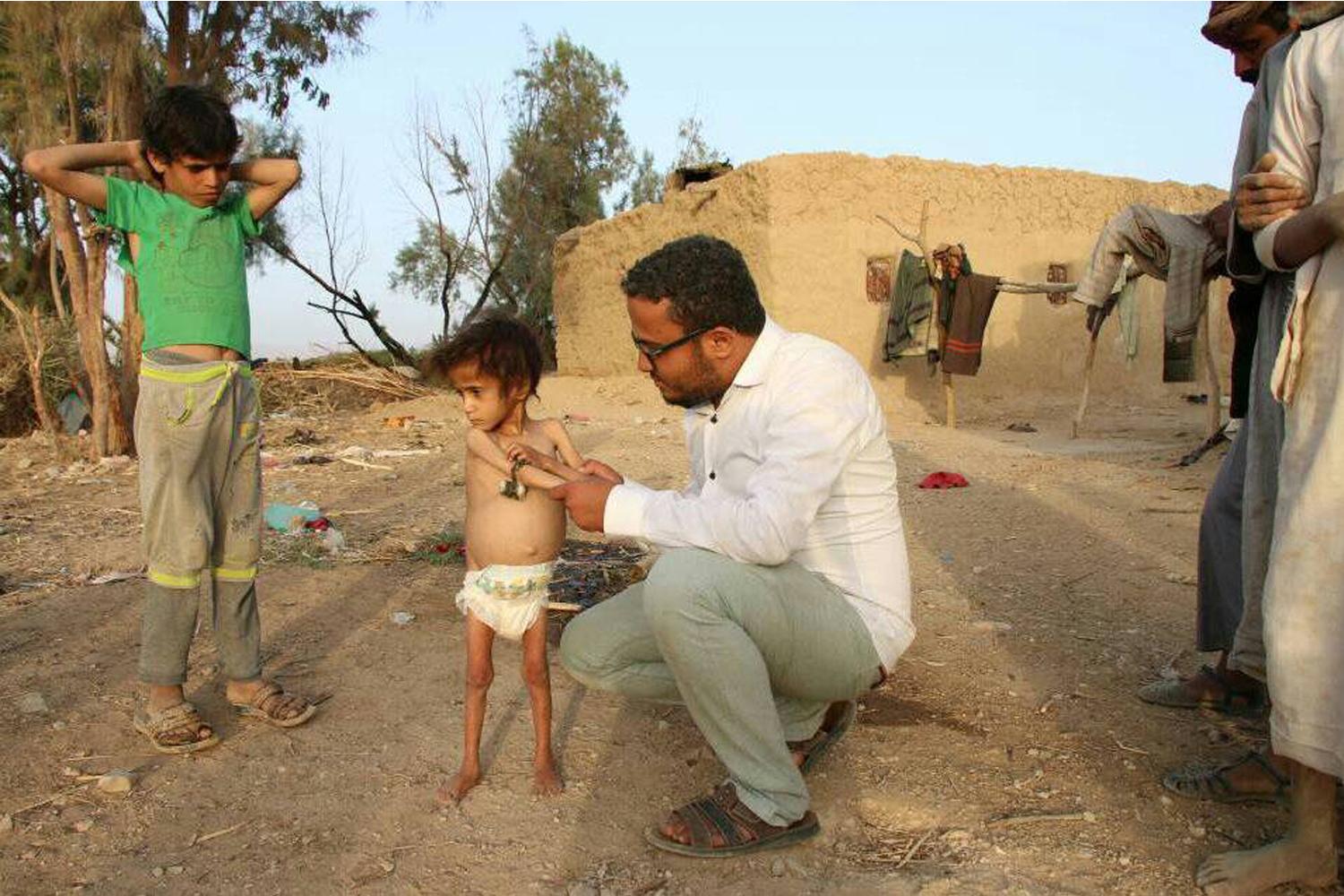

Batul Ali Alansi, 5, with Ahmad Algohbary in the village of Mathab, Saada governorate in northern Yemen, April 2017

A 24-year-old Yemeni man has put his English fluency, social media savvy and a passion for photography to good use. By doing what he's good at, Ahmad Algohbaryhas been saving young victims of Yemen's devastating famine.

Unfortunately, he hasn't been able to save them all. Algohbary lost a 5-year-old girl, Batul, who succumbed to cholera in July. Thousands of people had seen Algohbary's photos of Batul — first as a near-skeleton, then as a round, healthy little girl fully recovered from malnutrition.

After her father buried her body, he phoned Algohbary.

Batul’s family knew him as a benefactor, driver and cheerleader in the campaign to restore her to good health.

“I saved her from malnutrition and she was good,” says Algohbary. “She was playing with kids, she was playing soccer with the young children, so she was really fine. And she got better,” he says. “I didn't believe that cholera would kill her.”

Jamal

In a country where most people must skip meals, malnutrition hits the youngest family members first. It stunts children’s development and, if left untreated, it can kill them. War, a collapsed economy and an air-and-sea blockade of Yemen — enforced by Saudi Arabia with US backing — have left 17 million Yemenis struggling to avoid hunger.

Childhood nutrition was not on Algohbary’s mind one year ago. Then, he was focused on his own losses from the Yemen war: A best friend killed in an air strike, his university classes cancelled as foreign faculty fled the country.

His education on hold, Algohbary picked up his camera. He documented the struggles of war survivors on long road trips across bombed out regions of northern Yemen, publishing the most powerful images on Twitter.

“I posted a photo of Jamal,” Algohbary says. “He was suffering from malnutrition. I posted the photo, and a donor said that she wanted to donate for this child.”

At the time, 120 people had been following Algohbary's Twitter account. One of them, an American, sent the first donation that would set him on a new path.

“Jamal is the first little boy that Algohbary was able to help, which really marked the start of his aid work,” says Jamila Hanan, an online activist who followed Algohbary's tweets from her home in the UK. “Ahmad had tweeted a photo of Jamal, 4 years old, looking extremely malnourished, and a lady abroad saw the tweet and responded, asking if she could send money to ensure that Jamal would receive the care he needed to get better.”

While nutrition treatment is available for free at centers funded by UNICEF, Yemeni families in poverty can’t afford to travel to the clinics. “And even if they do get there,” says Hanan, “they cannot afford food and accommodation for family members to stay with the child for the duration required for the child to return to good health.”

Jamal was admitted to the UNICEF clinic at al-Jamhouri hospital, in Saada, Yemen’s northernmost province.

“What Ahmad did, in effect, was sponsor the family of Jamal to ensure he could stay in the clinic for a full month until he had returned to good health, almost certainly saving his life,” says Hannan, who followed Jamal’s recovery through Algohbary’s social media posts.

Algohbary posted photos showing Jamal's recovery. Hanan reposted them for her 75,000 Twitter followers.

While tending to Jamal’s family at the nutrition center, Algohbary was approached by other families. “Why didn't you give to our children, because they are suffering like Jamal, the same, from malnutrition,” he recalls.

“It was clear that he wanted to take this further and he wanted to do this again,” Hannan remembers. The UK activist had the skill set to assist him. “I’m also a web developer,” she says, “so I was able to build the website for him to support his cause. I suggested, 'Why don't you think of an actual name so you can register as an organization?' and that's what he's trying to do now.”

Mohammad

Algohbary settled on a name for the site, “Yemen Hope and Relief,” and with some assistance from others he was able to collect online donations to provide cash for Yemeni families. More people began watching his Twitter feed (nearly 2,000 followers now) and Hanan faithfully forwarded his tweets to the tens of thousands of people who follow her worldwide.

The next child supported by the fledgling NGO was Mohammad, an infant who was severely malnourished and in need of an urgent operation to relieve swelling on his brain.

“We were really aware that this little baby was definitely going to die without an operation that couldn't take place at the local clinic, and would require a significant amount of money to transport him to the hospital [in the nation's capital, Sanaa],” says Hanan. “So we had this huge fundraising activity — lots of tweets going out.”

She helped Algohbary come up with a plan that would cover the family's living costs, transportation to and from the hospital, plus food and lodging for Algohbary. It would be a barebones budget by anyone's standards.

"We collected $800 for the child and $200 for my travel costs," says Algohbary.

He borrowed his dad's car, filled up the gas tank, and drove the rescue mission.

Helen, a retiree in New Zealand who asked that we not use her last name, followed Ahmad Algohbary on Twitter. She was one of the first to respond to his call for funds. “How do I donate effectively?” she remembers asking herself. “Because [with] the big organizations you just don't see anything. I just wanted to get funds directly for these children that Ahmad was showing a photograph of. And make a difference.”

Mohammad, already weak from malnutrition, did not survive the operation. Mohammad’s family invited Algohbary to help them bury the boy’s tiny body.

Batul

Dr. Ali Mohamed Al-Kamadi, a pediatrician in the UNICEF-funded clinic at al-Jamhouri hospital in Saada, knew Algohbary had helped out families of some of his patients. “He showed me a picture of a girl,” Algohbary recalls. "She came to the nutrition center, but her family couldn't stay there because they don't have money.”

This was Batul.

“She [had] SAM [severe acute malnutrition] with celiac disease,” recalls Kamadi. Although his clinic treats as many as 70 young patients each day, he still remembers Batul. “She was in bad condition … with diarrhea, abdominal distension and a skin rash.”

Batul’s family, unable to afford a hotel or food for even one overnight in the city, had to take her back to their village and try treating her at home. Algohbary started publishing photos of the girl and collecting funds on Twitter.

“I asked where Batul is living," Algohbary recalls. "They told me in a village called Madhab.” With some urgency he packed up the family car and set off on his mission to rescue Batul. But reaching her family's village meant he'd be traversing rough terrain and hazardous roads in an active war zone.

He chronicled his harrowing drive in real time for his followers around the world.

Hanan was retweeting from the UK. In New Zealand, Helen was following online.

“He came under fire. He had to sit on the side of the road. There were bombs going off. He was exhausted,” she recalls.

Batul and her parents stayed in Saada City for a month, paying for food and lodging with money collected by Algohbary. “After she recovered from malnutrition,” says Algohbary, “she could play … do everything. Her father told me that. And I noticed when I visited her [that] after recovering from malnutrition she laughed, and she was, like, touching my hair and laughing. … It was a really amazing time.”

Batul’s recovery was widely celebrated online.

“Obviously it's such a drop in the ocean, what he's doing, tiny drop,” says Hanan, who helped get the word out. “But he's bringing hope, and he is connecting people with the personal story, which is absolutely vital. Without that human connection, it doesn't matter. The big efforts of the big aid agencies will never really connect with the public without those personal stories. And that's what Algohbary's doing with his aid work.”

Hope and relief

After helping Batul, Algohbary — as Yemen Hope and Relief — raised funds that would allow another little girl, Dua’a, to be treated at the clinic; then he helped an infant girl, Sohor, in her recovery. He is currently raising funds for a new rescue mission.

The recovery stories are bright moments in the ongoing story of Yemen's struggles with war, poverty and hunger.

In late July, Hanan got a disturbing text message from Algohbary. “It had a crying face [emoji],” she recalls, “and he had left me a number of recorded audio messages telling me that Batul had passed away and — the despair, really — just where do you go from there? He was asking me ‘what shall I tell people?’ People have raised money for her. And she's passed away. He was concerned about upsetting other people. He just couldn't think.”

“I told Jamila that I'm really broken,” Algohbary says. “I couldn't sleep, I was … alone in my room remembering everything. And I said 'I cannot, like, do this anymore.' But Jamila said, 'Ahmad, please move on,' and 'we have to save more children.'”

This was not the first pep talk Hanan gave to her Yemeni friend. She knew how to get him back on track.

“Well, we have our faith, you know. We are both Muslim, and we do believe that things happen for a reason. We do accept when tragedy hits us. It hurts, but we accept it. And that's really what we have to say to each other, you know: Allah knows best, God knows best.”

“We don't have control over what happens," she says. "After Batul, others will die as well. We have to be prepared for that. But we just have to continue, and we have to keep offering hope and encouraging people to join us."

In New Zealand, Helen talks about the connections she feels now with families in Yemen through her friendship with Algohbary and Hanan, who live on different continents. “It has made me more aware, I think, that we’re not that far apart.”

She shares a thought she had one night after spending time on Twitter, following events in Yemen. “I looked at the moon and I was looking at the stars. And suddenly I realized, it was my neighbor. It was my back door in comparison to the universe, and therefore, they weren't that far away.”

Helen, like many of Ahmad Algohbary's online friends, says she's grateful to be able to follow his journey. "He has an amazing heart, a beautiful heart," she says. "I know that these children become his children. I think they become our children."

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?