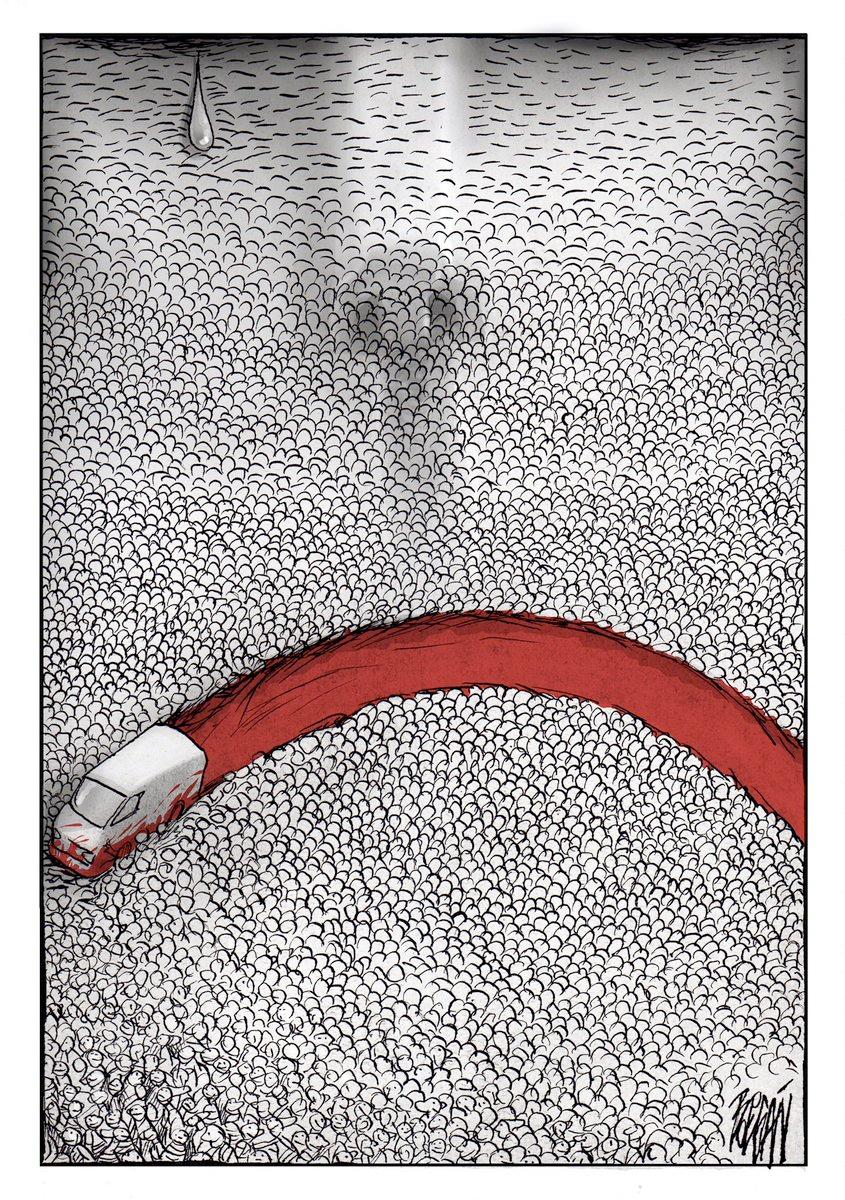

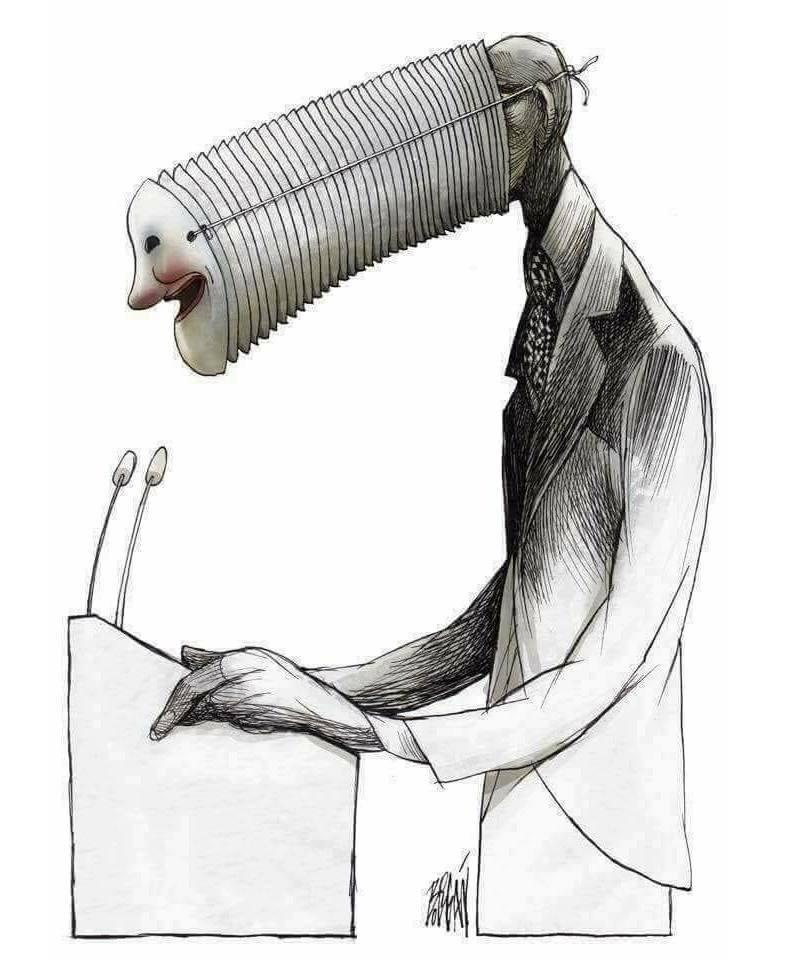

Left: Kim Jong-un as the class bully, El Universal Opinión, Mexico, Sept. 2, 2017. Right: Catalonia removes a key piece of Spain, El Universal Opinión, Mexico, Oct. 14, 2017.

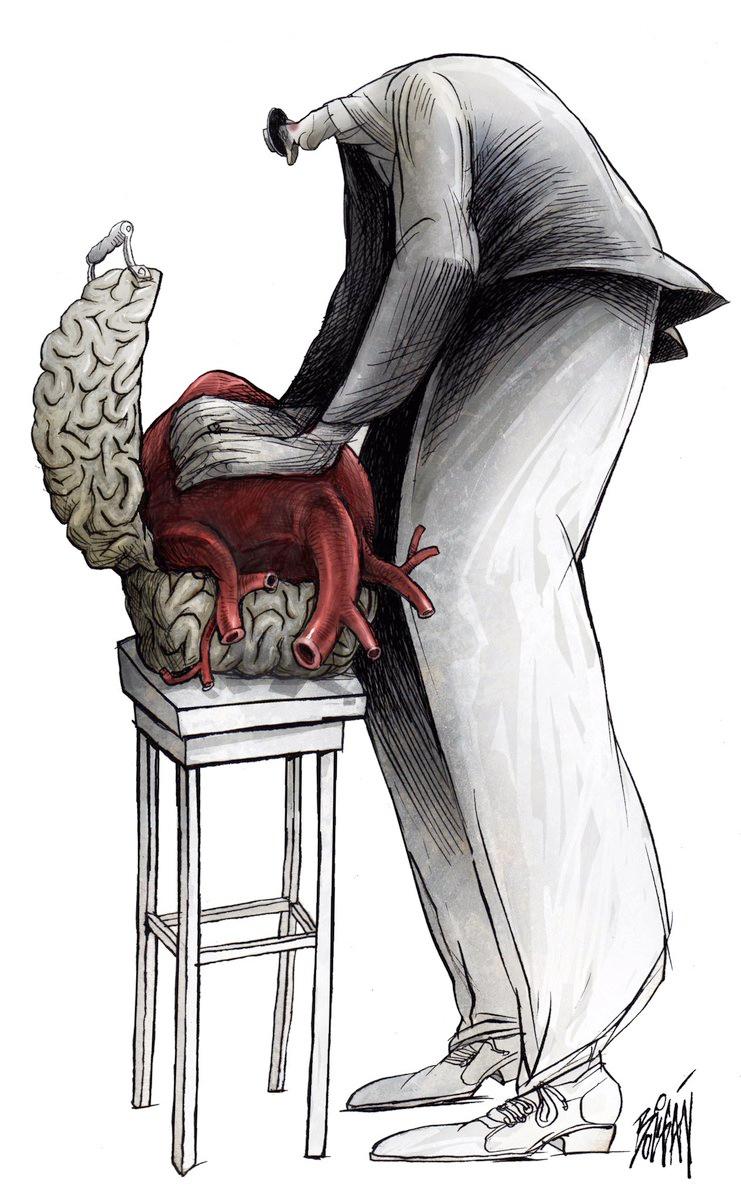

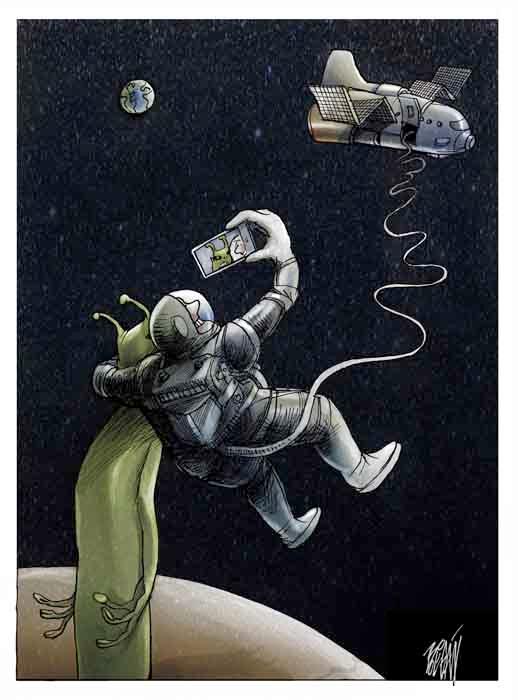

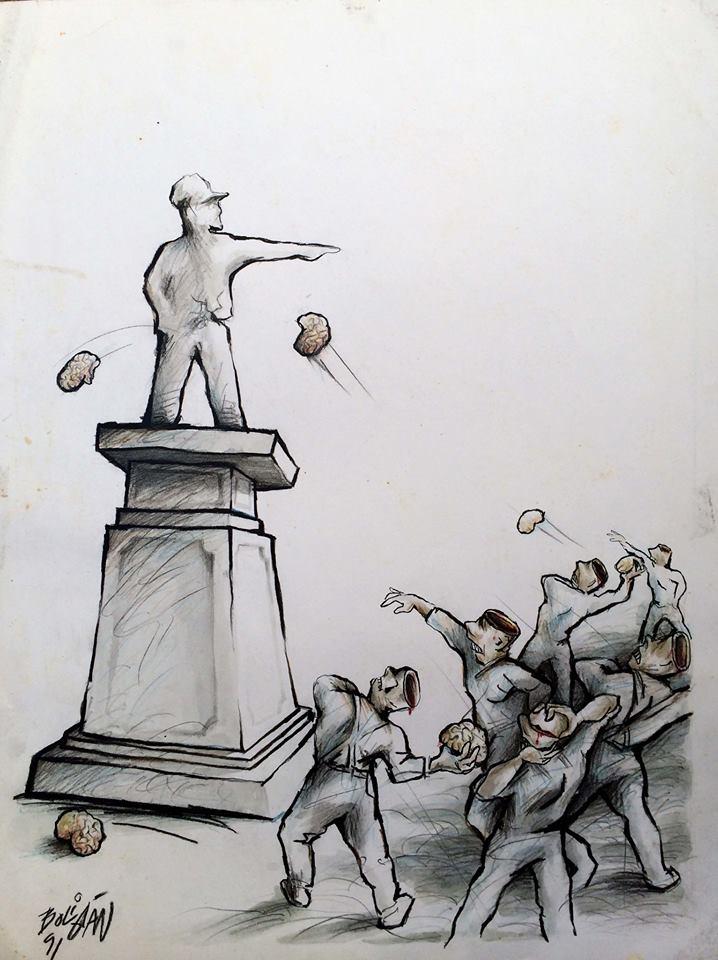

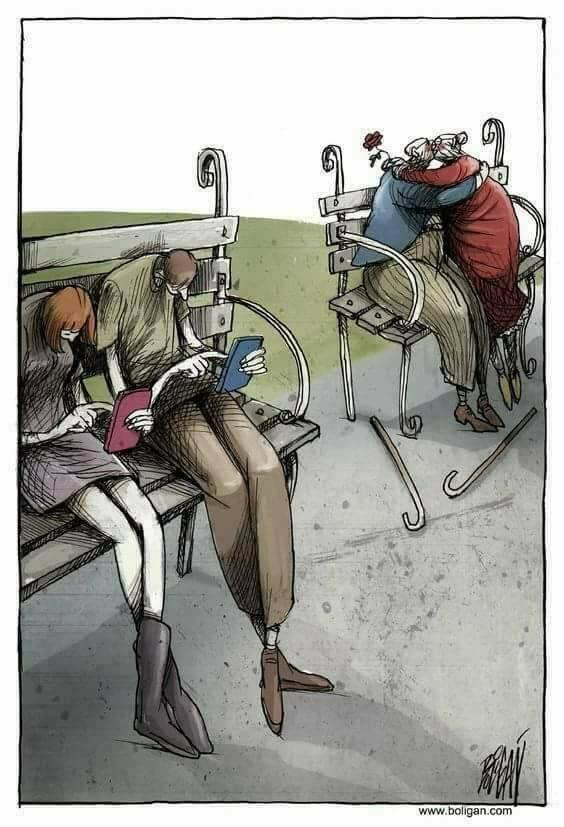

Cuban cartoonist Angel Boligán doesn’t draw to make hit-you-over-the-head political points. He draws to make you think.

There are no speech balloons or furrowed brows. In fact, you can barely make out the facial expressions of anyone in his cartoons. It’s their action (or lack of it) that he wants you to ponder. “For all the topics I like to draw, for me the most important thing is to be honest," says Boligán. "All my cartoons come from my heart and my soul. I want them to be authentic.”

Boligán doesn’t need to worry about authenticity. When you see a Boligán cartoon, you know it’s a Boligán cartoon.

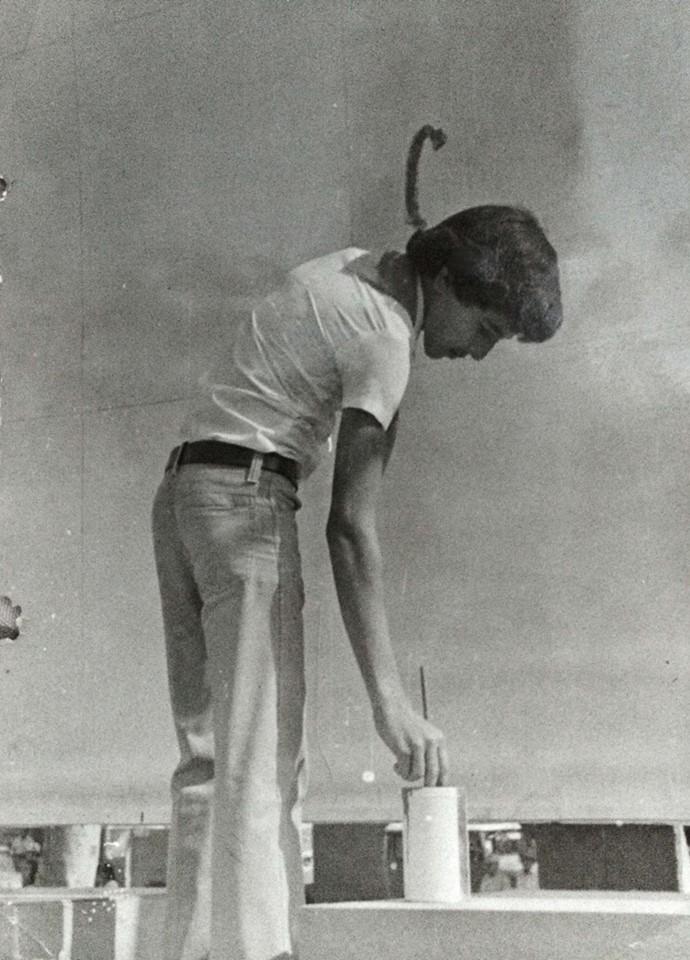

Boligán says his style is a fusion of different influences. "When you're young and you're starting out as a cartoonist, you want to have your own style. But it's almost impossible. Along the way, though, as you grow and meet other cartoonists around the world, without thinking about it, you start to absorb and capture their styles and influences. And then one day, people start to talk about your style.”

Boligán grew up in Cuba but has lived in Mexico since 1992. His tools of the trade are ink on cardboard. These days he gets his color from Photoshop but occasionally he still uses watercolor and pencil. Boligán cites Americans Saul Steinberg and David Levine as important influences on his work, but his singular surreal and wordless approach has a lot to do with the artistic trends and cold, hard politics of his homeland: Cuba.

Boligán literally grew up amid cartoons and satire. His hometown of San Antonio de los Baños, outside of Havana, is known as Cuba’s humor capital. “In 1917, my hometown held the first exhibition about cartoons and about drawing ever in Cuba.”

Over the years San Antonio de los Baños has become a center for visual arts. It hosts Cuba's Museum of Humor, the first of its kind in Latin America, and since 1979 has hosted a biennial Festival of Humor.

Cuba also has a long tradition of cartoons and satire. "Cartoons are considered art, not just as drawing. It’s part of the arts in Cuba," says Boligán. "It's one of the reasons that me and my colleagues don't see ourselves as journalists. We see ourselves as artists, graphic artists. We give something more to journalism. It’s complementary, drawing as an art, and journalism.”

Boligán soaked up all that his hometown had to offer. And by the time he entered art school in Havana in the mid-1980s, Cuba was smack in the middle of what some have dubbed a Cuban renaissance, a 20-year period of experimentation among artists now considered a movement, the New Cuban Art.

Rachel Weiss has written a book on the New Cuban Art, and says the artists on the vanguard during this period were literal products of the Cuban Revolution. They were all born around 1959. "These were not counter-revolutionaries. These were not people who wanted Fidel [Castro] to go away. They considered themselves to be authentically revolutionary and they saw themselves as artists, an important part of that process."

Some of them were satirists, cartoonists, and multimedia artists who worked for a revolution-approved Cuban humor magazine called Dedeté, a play on the banned pesticide, DDT, that had been used in the US. And they pushed satire into areas it hadn't gone before by creating art that reflected Cuban reality instead of the Cuban dream. Their work touched on issues like scarcities, corruption and nepotism, and they dared to question whether the US embargo was really to blame for everything.

"It's inherently Cuban to talk back to power," Weiss says. “It’s important to understand that in the Cuban context, humor is not considered to be a lower form of expression. It’s a really important cultural form.”

"I think that maybe we wanted to remove the headaches of the head with humor," he says.

And raising questions about the world is Boligán in a nutshell. In that way, his approach is different from most political cartoonists, who typically focus on the news of the day.

"I think style comes not just in the way you draw, but also in the topics you choose, and the metaphors you use. I always try to make my cartoons universal assuming that the whole world will see them."

Boligán was in his early 20s and just getting his career going when Cuba’s economy collapsed after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991. Energy supplies dried up and some of the publications that Boligán worked for stopped printing. A lot of Cubans were growing their own food. During the early 1990s, many Cubans, including many artists, left the island.

What’s interesting about Boligán, however, is that he wasn’t looking to leave. It was almost an accident that he did.

"I traveled to Mexico in 1992. I was invited to take part in an exhibition at the Museum of Cartoon Art in Mexico. I never intended to stay and live in Mexico. But on the same day that I arrived in Mexico, I got an offer from El Universal — one of Mexico's biggest daily newspapers, and it was where, in my opinion, the best Mexican cartoonists work."

Boligán took the job and the move to Mexico changed everything for him. He went from publishing one cartoon a month in Cuba to having a whole range of outlets for his work in Mexico, including a major daily newspaper. He also found himself part of a larger cartoonist community and started exploring new ideas like love, consumerism and our obsession with technology.

"In Mexico, I did find the space and the freedom to tackle subjects that were a lot harder to talk about in Cuba," including a no-go zone for anyone in Cuba: Fidel Castro.

In 1998, when John Paul II became the first pope to visit communist Cuba, Boligán, now in Mexico, did what he knew his cartoonist colleagues back home couldn’t. He drew about it. His cartoon showed Castro cleaning out the cobwebs of churches in advance of the pope’s visit.

"My friends in Cuba could draw about it but their cartoons wouldn’t be published. I’m not a religious person but I respect those who are," he says.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

These days Boligán is in high demand. Besides his day job with El Universal in Mexico, he exhibits his work internationally and has won countless awards. And he feels slightly uncomfortable that his being based in Mexico and having more freedom to distribute his work means he gets more attention than his cartoonist friends back in Cuba.

But he remains close to Cuba and close to his cartoonist friends who still live on the island. My enduring image of Boligán is goofing around with a few of them at an international cartoon festival in France, where I caught up with him. By the way, he won first prize.