A stack of Charlie Hebdo cartoon collections in the publicity office of the satirical newspaper in in Paris.

Laurent "Riss" Sourisseau, a cartoonist and editor of Charlie Hebdo, arrives for his interview accompanied by bodyguards who hover outside the neutral office location where we talk.

They've been the cartoonist's permanent companions since January 2015, when the Kouachi brothers forced themselves into the offices of the French satirical newspaper and murdered his friends and colleagues in the name of Islam. Riss was injured in the attack.

The cartoonist says he's now living a second life and is both more pessimistic and more emboldened.

On the second matter, Riss is pleased about Charlie Hebdo's first-ever American experiment. It's in English, online, and will run for four weeks beginning Wednesday. The topic is "just something that interested me, like any story I'd pursue." In this case, it's leftist politics in America.

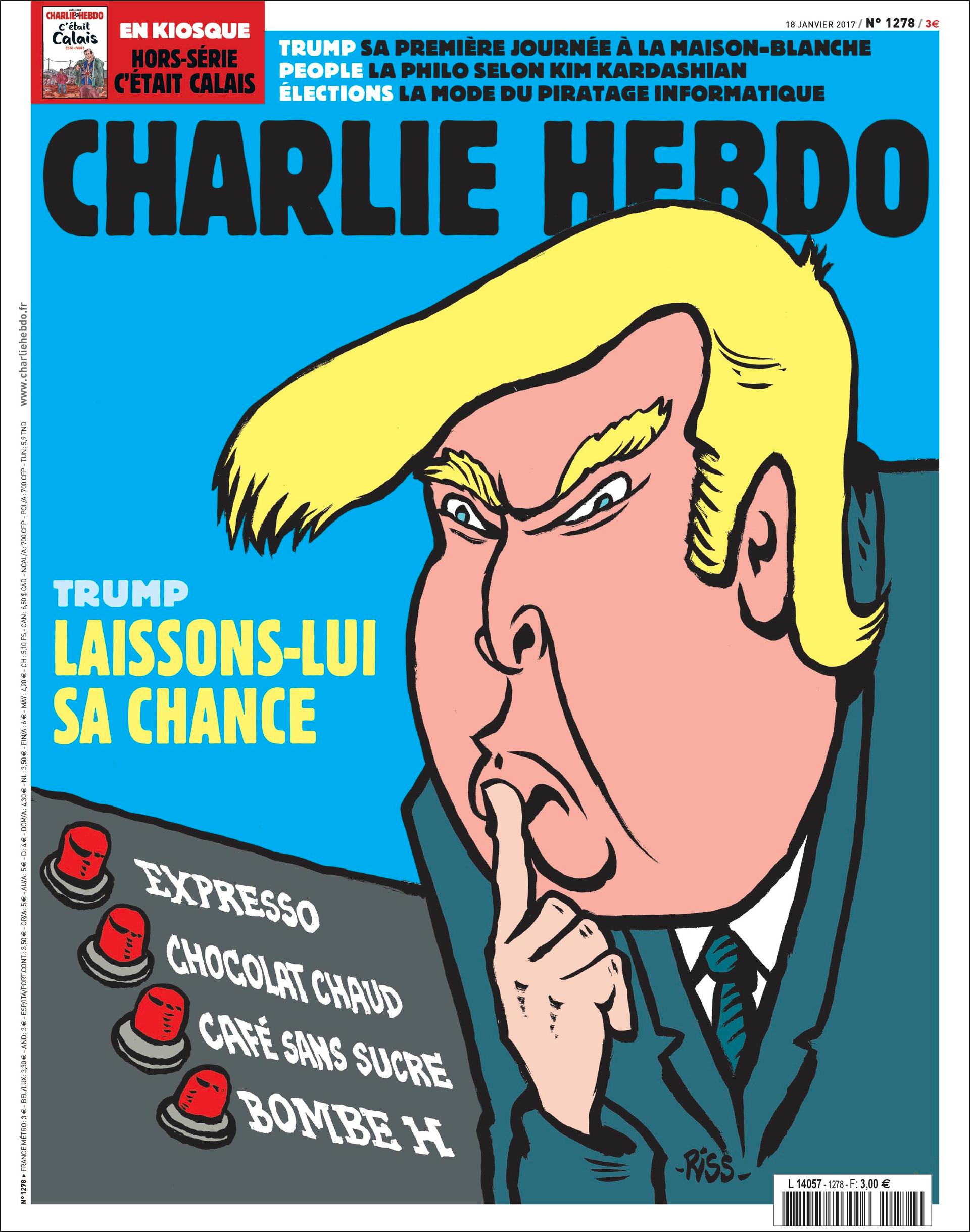

The idea came to Riss after the unexpected victories of outsiders Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump. In France last spring, the traditional leftist party, the Socialists, were trounced early on in the French presidential campaign. Riss was curious: How are leftists in America faring under Trump? So he went to the United States with American journalist Jacob Hamburger to find out.

Riss doesn't pretend he's going to school Americans. "I didn't go because I wanted to teach Americans anything. I was just curious."

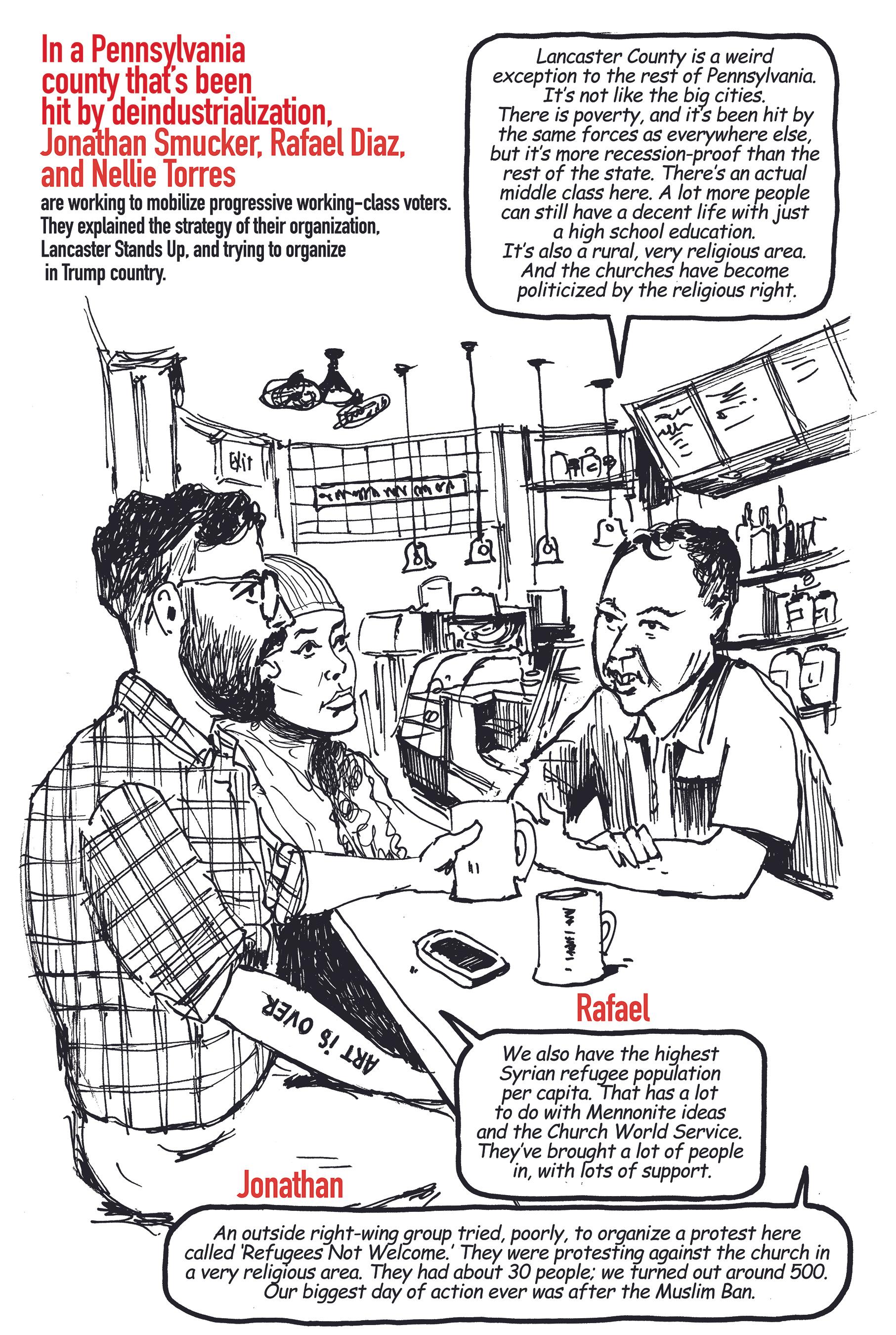

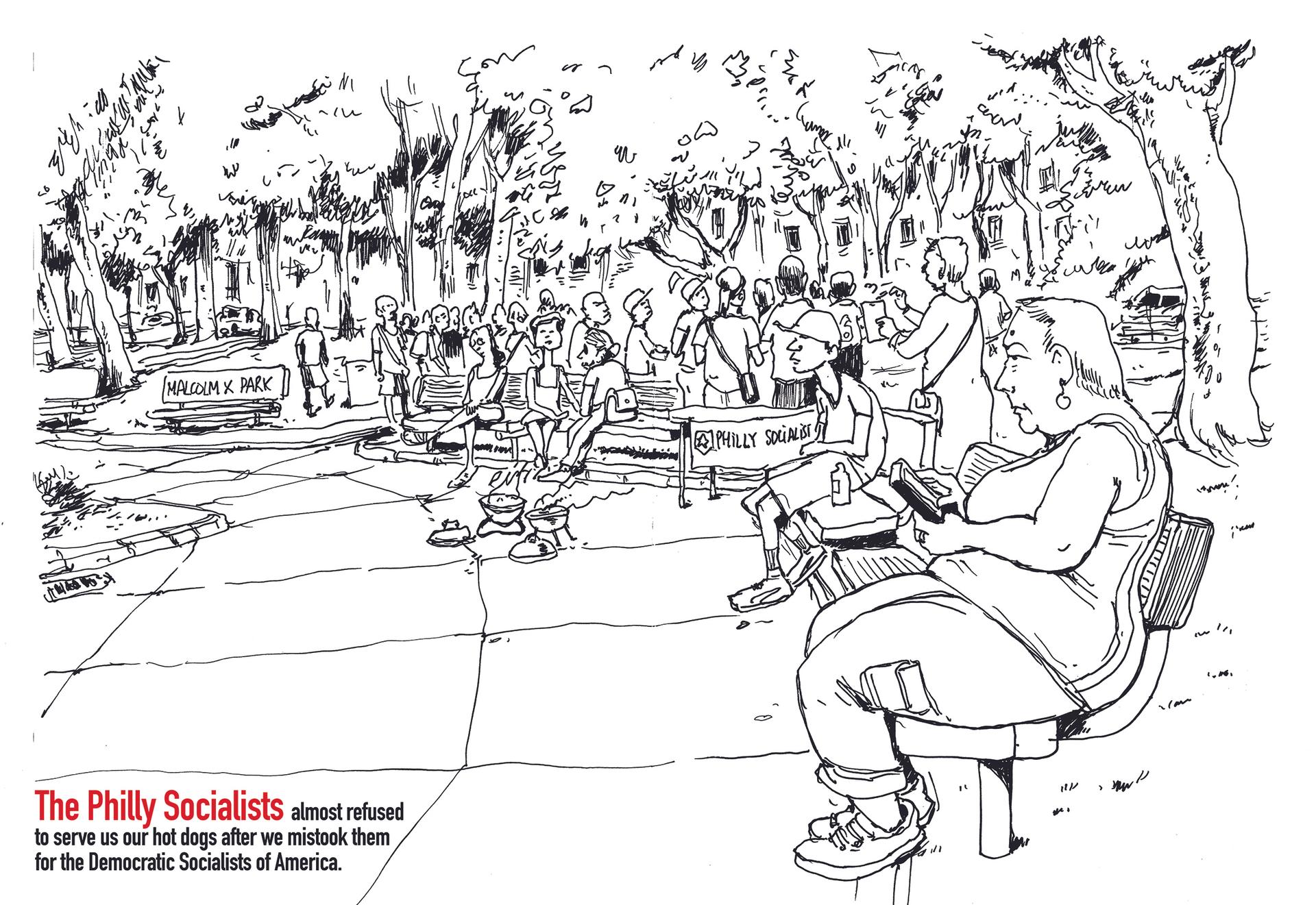

The result is the American four-part series: "Feeling the Burn: the Left Under Trump." It's really an expository cartoon exercise, with sketches and comments from grass-roots activists on issues ranging from immigrants' rights to the Green Party to union organizing, in places from Camden, New Jersey, to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

What Riss learned: "The further left you get, the more fractured you get." Like in France, he found that in America, each left-leaning coalition wants to be distinct from the others; because of that, they don't gain much political power.

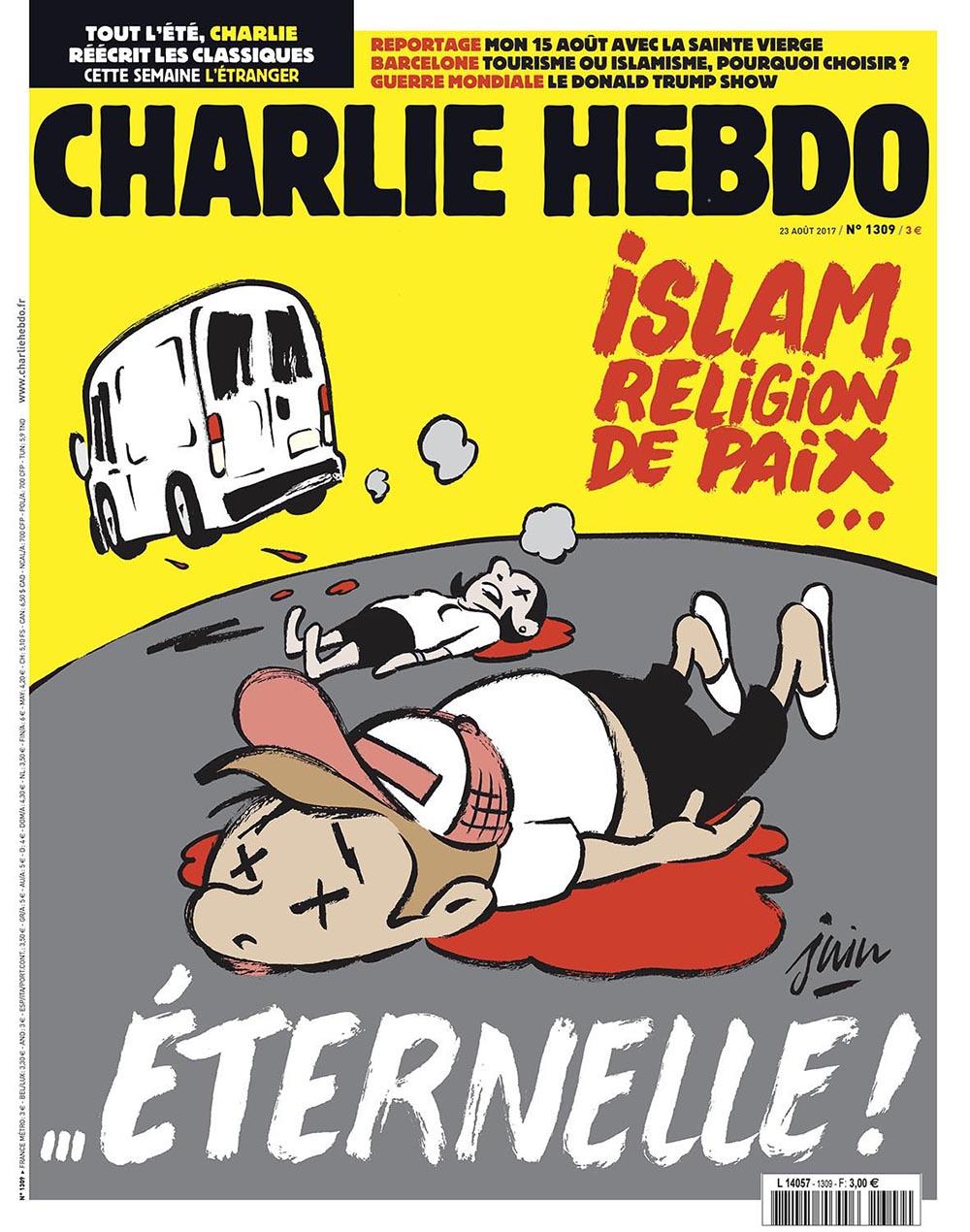

There are no jaw-droppingly, eye-raisingly offensive cartoons in the American edition. But those are what make people so mad at Charlie Hebdo. So I asked Riss about the cartoons that critics call Islamophobic. Like this one.

"It’s just to show how the male character in the picture is trying to downplay the violence of his action," says Riss. "This was in response to accusations that our newspaper equates Islam with fundamentalism or terrorism. So we’re showing that there is a discrepancy between the message and the action. We’ve done this kind of thing with other religions."

And they have. Since its founding in 1970, Charlie Hebdo has pilloried the Catholic Church, the bourgeoisie, politicians and anyone who acts like they're above the law. Questioning religion and enforcing France's secular state is at the heart of what Charlie Hebdo is. France hasn't been run by kings for some time now and Charlie Hebdo makes sure you never forget that.

But some people believe the newspaper has gone too far with its recent target: Islam. Here's the cover cartoon of Charlie Hebdo after the August terror attack in Barcelona when a van driver mowed down pedestrians in the city's most popular street, Las Ramblas.

Riss says the cartoon was trying to question the adage that's always said after a terror attack committed by Muslims, that Islam is a religion of peace.

"We think that there’s a stereotypical discourse about Islam, represented by this catchphrase, 'Islam, religion of peace.' So we gave that phrase an ironic slant in the headline because it sounds like a superficial commercial tagline. The idea is to encourage a conversation about the issues that exist within Islam. And I don’t think it’s being Islamophobic to just want to ask those important questions."

Riss insists it's not about the believers.

"In a democracy, everyone has the right to practice a religion and Charlie Hebdo respects that right, but we also have the right to question what all religions claim, starting with the claims that God exists and everything that stems from that."

Riss says Charlie Hebdo focuses on the writings of major religions, and that most of those texts at some point or other advocate violence. Charlie Hebdo is equal opportunity offender. A recent cartoon showed a 16th century massacre of Protestants by Catholics. The caption, said by a Catholic doing the killing: "It's not a massacre. It's just a neighbor's party."

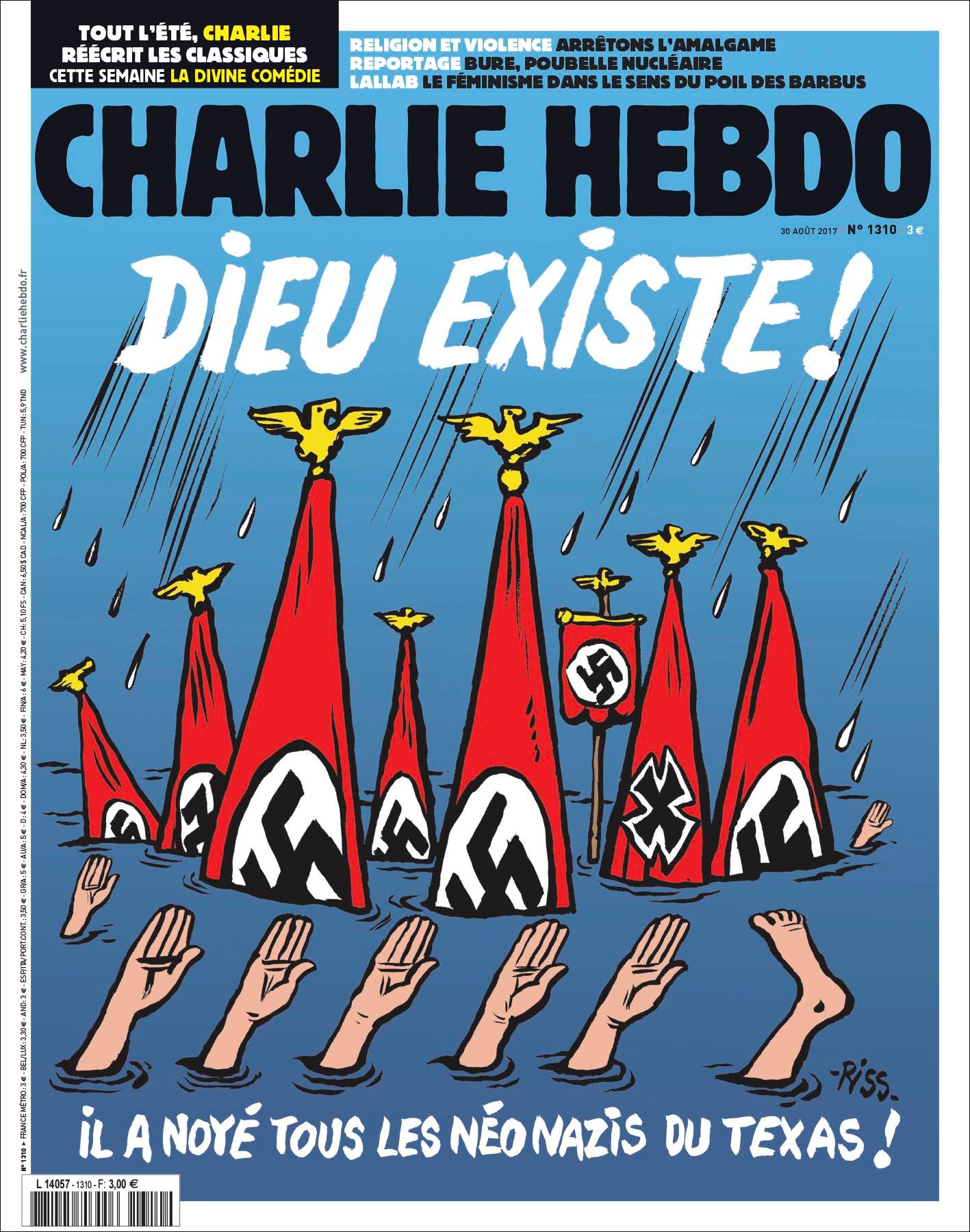

In August, after Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, Charlie Hebdo offended many Americans with this cover cartoon by Riss.

"This is about two conflating news events, a climate one and a political one," says Riss. "We saw the surge of the far-right and neo-Nazis movements in the South, like Charlottesville. We’re finding out those people are free to walk around. And because we assume many far-right people are very religious, we used an ironic slant to say, ‘yes, God exists and he drowned you all.’ It’s supposed to crack a joke at the expense of neo-Nazis."

Riss may have missed the mark with this cartoon. Religious conservatives and neo-Nazis are hardly interchangeable. But his point is that there are layers to Charlie Hebdo cartoons, layers that need to be explored, which is oh so very French.

But isn't that demanding too much of one's readers? Riss doesn't think so.

The story originally misstated the date of the terror attack in Barcelona. It occurred in August.