The 1966 Fulbright hearings on Vietnam parted the curtains on President Johnson’s conduct of the war

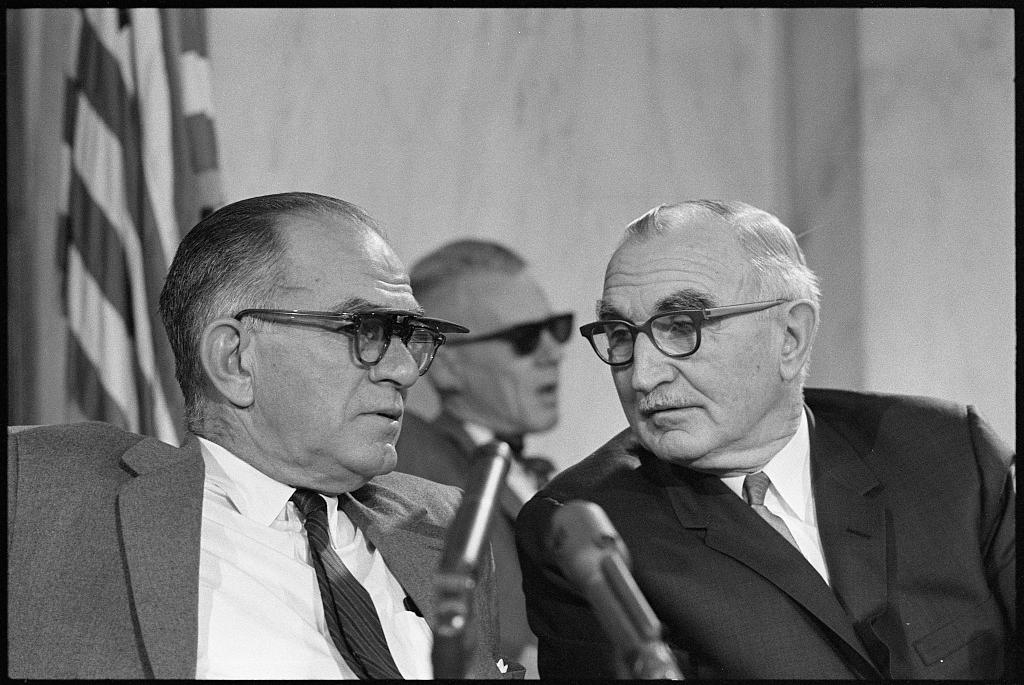

Sen. William Fulbright (left) is shown with Sen. Wayne Morse during a meeting of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966. After the incidents in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964, Morse and Ernest Gruening were the only senators to oppose a congressional resolution giving President Lyndon Johnson wide latitude to prosecute the war in Vietnam. Fulbright helped pass the resolution but soon came to believe Johnson had lied about the Gulf of Tonkin.

In February of 1966, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee convened a series of public hearings to question a range of experts on the progress of the Vietnam War.

The committee had held hearings before on Vietnam, but never in a televised, open session. On the rare occasions when the president had spoken of it, he had been less than forthcoming about what he knew and what he was doing.

These hearings began to part the curtains. Improbably, they became a national event and, for Lyndon Johnson, an unwelcome challenge to his conduct of the war. That they were presided over by Sen. J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, probably the most famous senator of his time and at one point a close ally of Johnson’s, made them even harder for the president to tolerate.

“The most proximate reason that the hearings took place was Lyndon Johnson's decision to resume bombing North Vietnam,” says historian Marc Selverstone.

Related: The carrot and the stick: LBJ addresses the nation on the conflict in Vietnam

In December 1965, Johnson had reluctantly instituted a bombing pause. He had been encouraged to do so by a number of his closest advisers, including Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. By the end of 1965, Selverstone says, McNamara was increasingly dubious about America's ability to prevail militarily in Southeast Asia.

The president shared McNamara's desire to bring North Vietnam to the conference table but was unpersuaded that a bombing halt would achieve that objective.

“Johnson [feared] that a bombing pause would only allow North Vietnam to infiltrate more men into South Vietnam,” Selverstone says, “and he [recognized] that he [was] going to get incredible heat from conservatives, as well as from the military, the longer this pause [continued].”

After 37 days, the president decided to resume the bombing and sent Gen. Maxwell Taylor to the Hill to try to get Congress and the public behind the decision.

“The Hanoi leadership is not yet convinced that it must mend its ways,” Taylor told the committee. “They doubt the will of the American public to continue the conflict indefinitely. Until it becomes perfectly clear to them that we are going to stay on course, regardless of anything they do, I'm afraid we're not likely to see them at a conference table.”

LBJ had come to see the hearings as a direct and dangerous assault on his conduct of the war. He defended his actions by repeatedly citing the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave the president what he considered virtual free reign to prosecute the war as he saw fit.

Listen to Johnson tell Louisiana Sen. Russell Long how to use the Tonkin Resolution to defend his administration.

Congress had passed the resolution 18 months earlier by an overwhelming majority. But William Fulbright, by this point, had begun to understand that he and the entire Congress had been duped.

Today, most scholars believe the alleged attack on American destroyers that President Johnson used to secure the Tonkin Resolution never happened. Doubts about the White House account began to surface soon after, but Congress had already passed the far-reaching resolution, thanks in no small part to a key endorsement from Fulbright.

“I believed what we were told about it in the committee,” Fulbright said. “No one had the skepticism that is essential, I’ve since discovered. We accepted it. I had no feeling that there would be a disposition to misrepresent what actually happened.”

As more intelligence began to emerge about what transpired in the Gulf of Tonkin, and about the conduct of the war itself, Fullbright’s attitude changed dramatically.

“I felt that I had been taken,” Fulbright said. “They weren't trying to stop the war at all; they were trying to win it. What his motives were and what moved him to pursue that policy has always been a mystery to me. I tried what best I could to persuade him not to.”

When Fulbright realized he could not influence Johnson personally, he decided the only hope “would be then to take it public and to have a public discussion of it.”

Johnson was enraged. He viewed Fulbright’s behavior as unpatriotic and disloyal — and, for Johnson, “being disloyal was probably the highest crime there was,” Selverstone says.

The hearings marked the end of Fulbright’s influence with Johnson.

“He struck him from the White House invitation list. They never had a personal relationship again,” Selverstone says. “They went through the motions to some degree … but it was the end of their close association. It was the end of their friendship.”

In the short term, the hearings did little to change policy. American troops continued to flow into South Vietnam. About 400,000 troops would be in Vietnam by the end of 1966. Johnson would, in fact, intensify the bombing.

On the other hand, Selverstone says, the hearings legitimized public dissent. America began to have a conversation about Vietnam that they hadn't had before. By August 1967, a plurality of Americans came to believe that the war was a mistake. That shift in public opinion began with the Fulbright hearings of February 1966.

Read more on LBJ and the Vietnam War: What really happened in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964? and LBJ knew the Vietnam War was a disaster in the making. Here's why he couldn't walk away.

Correction: The caption for this story originally stated that Wayne Morse was the only senator to oppose a congressional resolution giving President Lyndon Johnson wide latitude to prosecute the war in Vietnam. Sen. Ernest Gruening also opposed the resolution.

This article is based on the PRI podcast, LBJ's War, hosted by David Brown. Subscribe to LBJ's War on Apple Podcasts.