An antifa activist carries a flag of the movement, which features a logo of two flags.

The Signal messages appear in staccato bursts:

“We all in blac bloc bout to join.”

“We in the streets.”

Looking up from my cellphone, I see them coming: a platoon clad head to toe in black, marching in formation like some sort of dystopian Roman legion. They’re carrying flags and holding shields, some embossed with the black-and-red logo of the anti-fascist movement.

As they approach the column of protesters already marching toward Berkeley City Hall, they start banging on their shields, chanting:

“Ah — anti! — Anti-fascista! Ah — anti! — Anti-fascista!”

Hundreds in the main crowd — from small children to white-haired peaceniks — join in, “Anti-fascista! Anti-fascista!”

This dramatic moment marked a historic coming together of mainstream San Francisco Bay Area leftists and these combative protesters known as antifa. Spurred by the deadly events at a racist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, two weeks earlier, leaders of the anti-hate march invited local antifa to form a “black bloc” — moving in formation, wearing black — to protect their Aug. 27 march on a planned right-wing rally in downtown Berkeley, California.

Deep inside the bloc were the most militant members of the opaque group, who had been busy for weeks with a different plan. They had tracked conservative activists across the Bay Area — and beyond. They held meetings and created a database of known targets, invariably labeling them “Nazis.”

Their most-wanted list stretched the definition of “Nazi” to include figures such as Joey Gibson, a conservative agitator who publicly denounces white supremacists. Antifa sources consider Gibson guilty by association because white supremacists regularly show up at his rallies. And the list held more obvious lightning rods, including anti-Semitic blogger Johnny Monoxide, white nationalist Richard Spencer and Nathan Damigo, who founded the white supremacist group Identity Evropa.

One antifa activist, who would give only the name “Dominic,” talked proudly in a series of interviews with Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting about forming this broader alliance of “Nazi hunters” to seek out, reveal and fight these enemies wherever they might show up. Their goal became even more specific after Charlottesville: to prevent more casualties like that of activist Heather Heyer.

“We’ll go to their house, I’ll put it that way. We’ll go to their house,” said Dominic, an imposing, muscular man in his 30s. “I don’t want to hurt anybody, but I want those people to stop it. If I have to put Richard Spencer or Nathan Damigo into the hospital critically, and it would have saved Heather Heyer’s life or the next potential Heather Heyer, I would do it without question.”

These radical strategies have played right into the alt-right’s plan — and led to a backlash.

The targets on Aug. 27, known conservative provocateurs, fulfilled their oft-stated goal of becoming martyrs for their movement. They quickly appeared on news shows to describe how they were viciously attacked. Conservative media organizations labeled the antifa activists “thugs.”

Liberal politicians soon joined in. During the following week, Berkeley’s mayor, Jesse Arreguin, called antifa a gang and a militia. Democratic House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, who represents San Francisco, released a statement saying antifa protesters “deserve unequivocal condemnation.”

And on Friday, Poltico broke a story based on leaked documents indicating that the FBI and Department of Homeland Security consider recent antifa activity — including greater organization and funds — “potentially suspicious and indicative of terrorist activity.”

The months of reporting we have done on the Bay Area antifa suggest that there is no easy way to categorize the group. Some antifa activists are frustrated 20-somethings who enjoy dressing up in quasi-military gear and speaking grandly of defending their communities from invading fascists during rallies, but generally shy away from physical violence.

Others are intent on taking the fight against white supremacy and bigotry beyond the Bay Area, a ramping up of militancy that also stems from Charlottesville. The antifa’s Rapid Response Team has even taken the name of the slain victim of that far-right rally: the Heather Heyer Brigade.

Role playing and rapid response

The evening before a planned Aug. 26 right-wing protest in a San Francisco park, roommates Vincent Yochelson and John Cookenboo enjoyed a beer together in their ramshackle West Oakland backyard.

They checked their homemade riot gear. Cookenboo favors ex-military garb because it’s sturdy and cheap. Yochelson has taken a more hands-on approach, hammering out steel thigh plates and shoulder pauldrons. Decked out in his motley garb, Yochelson looks more like a live-action role player than a terrorist, perhaps because before he joined the ranks of the antifa, he was a live-action role player, joining friends in parks to re-enact medieval battles.

The two men, both in their 20s, and their friends see their role in protests as protectors. Prior right-wing rallies in Berkeley have attracted large numbers of burly militia members and angry white supremacists eager for a fight. Cookenboo said he positions himself between peaceful left-wing demonstrators and violent right-wing protesters who mean them harm.

“We go in as basically a protection force to work where the police cannot,” he said.

Cookenboo and Yochelson’s reward for their efforts back in April, at what became known as the “Battle of Berkeley” protests, was being arrested on suspicion of wearing a mask while committing an offense. Neither has been formally charged.

On Aug. 26, however, the two never put on their protective gear. The right-wing rally planned for San Francisco’s Crissy Field was canceled, and the counterprotest there soon turned into a rally that was more carnival than confrontation. Cookenboo’s helmet, emblazoned with one word — “antifa” — stayed in the trunk of his car.

But while the duo celebrated with San Francisco’s typical parade of colorful characters, across town, a more serious scheme was unfolding. The Heather Heyer Brigade had located its first targets and was closing in.

At about 3 p.m., Dominic and his crew got word that a handful of people had been spotted by one of their lookouts holding a banner reading, “Love Free Speech, Unafraid of Fake News, Ask Me My Point of View.”

They headed to Fisherman’s Wharf to confront the men holding the banner.

The Rapid Response Team was launched in the weeks leading up to the protests as a unit to protect marginalized communities from Nazis and fascists who mean them harm, according to Dominic and several other sources within the antifa and associated groups. The primary goal was to protect minorities and the LGBTQ community from attacks by right-wing agitators who have a history of targeting the liberal Bay Area.

But on this day, their aggression toward those more dangerous factions bled into a more general offense against basically anybody the antifa classified as opponents to their cause.

The handful of conservative protesters at Fisherman’s Wharf soon was surrounded by the black-clad group, who screamed at them, telling them to get out of town.

“They were way more aggressive and intimidating than the protesters, to be honest,” said Mike Gaughan, a pedicab driver who witnessed the confrontation.

After the protesters left, Dominic was triumphant and unrepentant. “We shut them down,” he said. None of the protesters at Fisherman’s Wharf were on the hit list, so things didn’t get violent, he added.

The next day, however, would be a different matter.

‘Stitches or broken bones’

Lost in news coverage of the flashpoints of the late-August protests in Berkeley is a simple fact: The vast majority of those who attended were peaceful.

Bay Area activist group Showing Up for Racial Justice had issued a list of guidelines for the day. Among them: No talking to white supremacists, no talking or responding to police officers, and no initiating violence toward white supremacists.

Several sources, who did not want to be named because of the growing controversy surrounding the antifa, confirmed that more moderate groups had been in discussions with members of the antifa movement for at least two weeks prior to the protest. In the past, more moderate liberal groups in the Bay Area have kept their distance from the antifa, leery of their violent tactics. But Charlottesville changed things. They now wanted antifa to be their defense.

Dominic spoke with obvious pride about those meetings. But in one crucial way, his plans for Aug. 27 differed from those of Showing Up for Racial Justice and other groups: He was willing to confront and even beat his enemies.

The tactic of identifying specific targets had been ongoing since the spring, when two successive protests in Berkeley descended into violent clashes between right-wing and left-wing demonstrators.

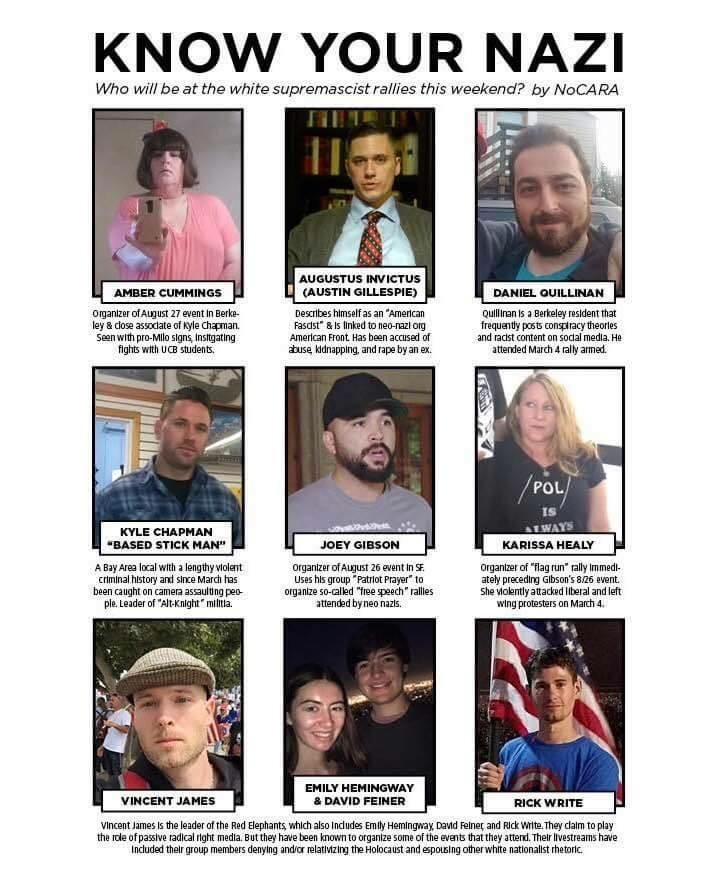

Activists within the antifa quickly assembled their hit list, which they included in an eight-page handout titled, “The Alt-Who? Violent Far Right & Fascist Individuals Coming to the Bay Area — April 15.” This list was supplemented by a one-page document forwarded online a few days before the August protests titled, “Know Your Nazi,” which included organizers of the conservative Bay Area protests.

Of the several scuffles in Berkeley, the one that has received the most attention is the chasing down of Joey Gibson, who organized and then canceled the San Francisco rally.

Gibson portrays himself as a nonviolent, nonracist victim but he is among the top targets of the Bay Area antifa — and was the central face on the “Know Your Nazi” flier.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DgsZC4Om3VKw

In an interview a few days before the weekend events, Gibson claimed that he was coming to the Bay Area to interview moderates and “normal liberals.”

“I’m sick of the extremists on both sides trying to tear apart the moderates,” he said.

But on that Sunday, Gibson ignored the thousands of moderate protesters who had shown up.

Instead, about 20 minutes after the Berkeley Police Department stood down and allowed protesters into the Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park, Gibson made a beeline for the most angry antifa. Flanked by a couple of supporters, including Tusitala “Tiny” Toese — decked out in football pads and goggles — Gibson strode into the black-clad crowd, waving his arms and making peace signs with his fingers.

“I come in peace,” he said.

Instantly, Gibson and his crew were identified. Video from the event shows a black-clad protester running around shouting that “the Nazis” have arrived. Gibson soon was surrounded and began backing away as protesters screamed at him and swung at him with their fists and flags.

As word spread through the black bloc, Dominic and his crew ran to confront their targets. One protester shot pepper spray at Gibson and Toese, who quickly retreated behind a line of watching police.

Keith Campbell, another antifa target with a history of rabid Islamophobia, fell to the ground and was kicked and hit. Campbell considers himself a journalist but had spent the days before the rally tweeting that he would be bringing a “heavy duty monopod” for his camera to Berkeley “to double as a weapon.” Campbell also told Reveal that he is a member of the Oath Keepers, a far-right anti-government organization whose members had at one point been expected to serve as the protective forces for the right at Gibson’s Crissy Field rally.

“What does he deserve? He deserves potentially stitches or broken bones,” Dominic said of Campbell. “He wasn’t gonna get killed that day, we were strategic.”

In the heat of the moment, the attacks on Gibson and Campbell might have seemed spontaneous. But there was nothing random about them at all.

“The people on our list are targets, so they got injured,” Dominic said. “They came in for a fight, came right into the center of thousands of people who have signs all over saying we stand against hate, knowing that we associate him with hate and the people he brings around him.”

Dominic considers driving out Gibson a victory for the antifa. It showed the discipline of the group’s foot soldiers, he said. But he also acknowledges that his definition of self-defense isn’t the same as most people’s.

And he has plans to stretch that definition even further.

‘Hunting Nazis’

When I first met Dominic a few weeks ago, in a sun-dappled park in Oakland, the first thing he told me was that he’s been “fighting Nazis for 20 years.”

The Bay Area activist describes himself as an anarchist. His protest history echoes that of the antifa movement in America. While its roots lie in Europe as far back as the 1930s, antifa as a concept first arrived in the U.S. in the late 1980s.

Alexander Reid Ross, an author and lecturer at Portland State University who writes about fascism, said the most visible element of the fledgling movement in America was a group called Anti-Racist Action, headquartered in the Midwest. Dominic says he was an agent for Anti-Racist Action in California.

Throughout the 1990s, he and others helped drive neo-Nazis and white supremacists out of the state’s punk rock scene, he said. They specialized in outing racists to friends, family and employers, he said.

The driving force behind Dominic’s activism is his deep conviction that fascism is on the rise in America in 2017, amplified by the election of President Donald Trump. Racists, he said, feel emboldened to speak hate and display hateful signs on public streets.

The violence in Charlottesville and the killing of Heyer only strengthened his resolve to take the fight to the various people he describes as “Nazis,” rather than waiting for them to come to him. By doing so, he said he is taking up the battle his grandfather fought on the beaches of Normandy in World War II.

“I think about the Purple Heart my grandfather got trying to fight against this fascism that is in a new phase now,” he said. “It’s sad to me that we have to still be fighting it in 2017, after a Holocaust and all these terrible atrocities — that people can still flirt with these ideas.”

When I first talked with Dominic, antifa as a concept was in the early stages of its rebirth — at least to the general public. Trump had yet to decry the movement. News outlets struggled with how to define this new movement that wasn’t quite an organization and seemingly had no leaders.

So did I. In the weeks that have followed, through Charlottesville and Boston and Berkeley, I’ve watched the antifa movement evolve. Every day, new Facebook and Twitter handles using the moniker pop up.

Originally, Cookenboo brushed off the title as a label assigned by others, not him. The day after Charlottesville, he painted “antifa” on his protest helmet.

At the vanguard of this evolution in the Bay Area are hard-core anarchists such as Dominic, who cut their teeth in Occupy and other previous movements. And in the weeks since we first met, Dominic’s thinking and planning also have evolved, from pushing racist agitators out of his home community to dreams of hunting Nazis once again, perhaps across America.

Other key antifa figures chuckled when I outlined Dominic’s plans. But he’s not joking. He sees the world as an increasingly unfair and divided place, led by a cabal of white supremacists enabled by a proto-fascist police state. What choice is there, he says, but to fight back?

Many on the left see the August events in Berkeley as a public relations disaster for the antifa and the broader left wing – making them look like out-of-control bullies. But Dominic remembers a different image: being hugged, high-fived and cheered on by members of the clergy, older women and kids as he and his black-clad comrades made their way toward the downtown Berkeley park where the antifa had been beaten up by opponents at another protest a few months before.

The day after, Showing Up for Racial Justice issued a news release quoting Isaac Lev Szmonko — an organizer with Catalyst Project, an anti-racist organizing and education collective:

“Many of us were not aware until today of the crucial role that antifa have been playing to defend communities against white supremacist violence, at great personal risk. Today we saw them put their bodies on the line to contain and remove violent threats one after the other in situations that could have become very dangerous, especially for the people of color, queer and transgender people, and women who were present.

“People were very grateful for the protection antifa offered.”

Truly overcoming white supremacy will require a strong alliance of many people, Dominic said. It will require unity and hard work, organizing and growth. And, as a last resort, violence.

When that is required, he said, he and others like him will be ready.

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast. ![]() This story was edited by Amy Pyle and copy edited by Nadia Wynter and Nikki Frick.

This story was edited by Amy Pyle and copy edited by Nadia Wynter and Nikki Frick.