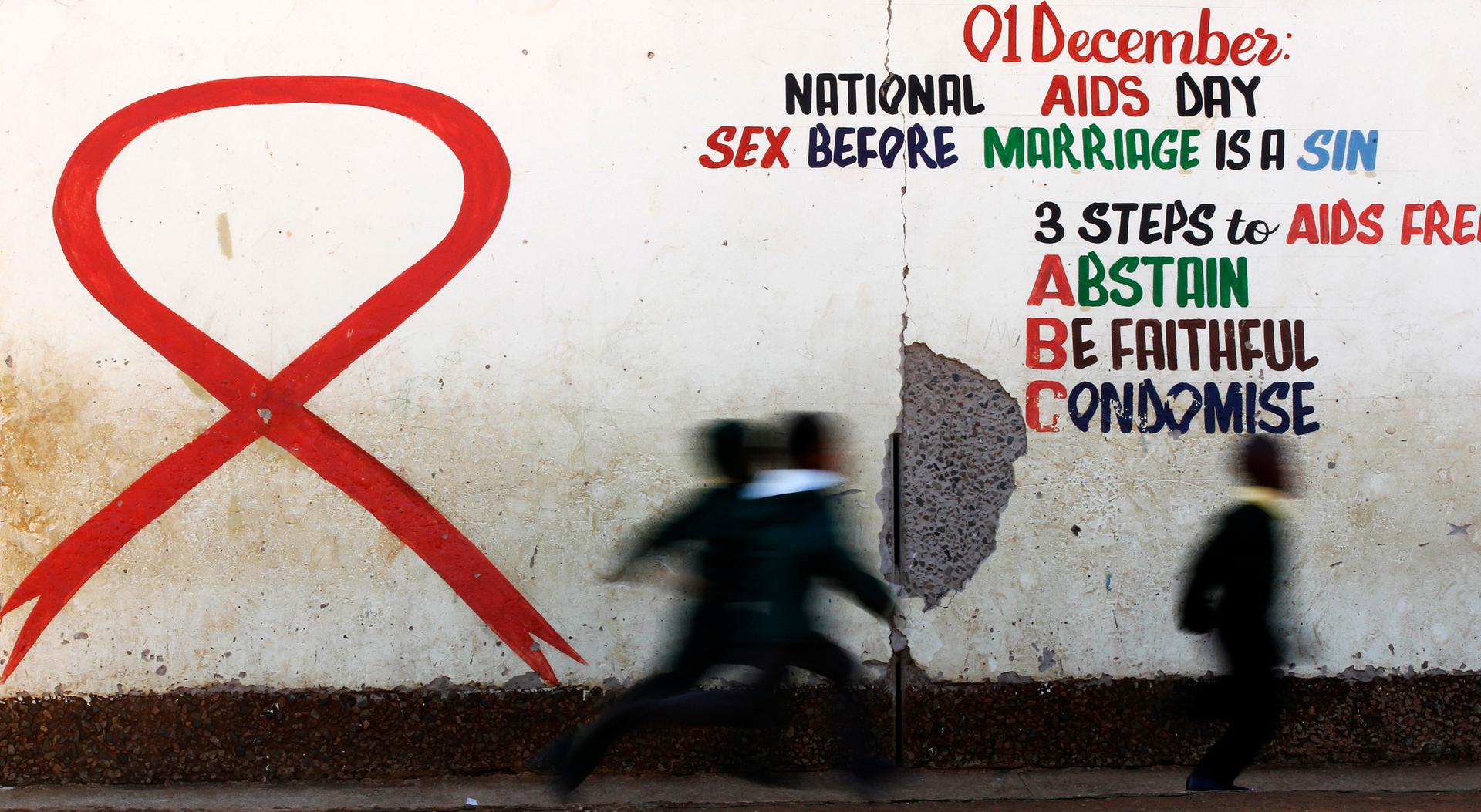

Children run past a mural painting of an AIDS ribbon at a school in Khutsong Township, 46 miles west of Johannesburg, on Aug. 22, 2011.

When Marlene Wasserman was a young woman, she wanted to study sex.

It’s ironic that she was interested in how people get together in the most intimate of ways because she lives in a country that is obsessed with keeping people apart.

“You’ve got to remember that we had censorship,” explains Wasserman. “There was sexuality censorship so there was absolutely no exposure to pornography, to sexuality education, to sex toys.”

South Africa was in the grips of apartheid — a brutal system of white minority rule that kept people of color separate from whites.

Sex wasn’t just taboo. Sex was dangerous. Legislation made sex between blacks and whites illegal.

“The only discourse around sexuality was an immorality act,” explains Wasserman. “If you were to have sex with a black person, with a white person, you would be locked up and sent to jail.”

And then, in the 1990s everything changed. Anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990 — the beginning of the end of apartheid.

By 1994, Mandela was elected president of South Africa and media censorship was lifted. People started talking, telling their stories. And one story that kept coming up was about this disease, which for years had been infecting people.

“It just took everyone by such surprise,” says Wasserman. “Like here, we’ve come into democracy, it’s this ‘rainbow nation.’ And look what we’ve inherited. We’ve got all these men who are dying of HIV. What does this mean?”

A decade of silence had left South Africa with an unchecked HIV/AIDS epidemic. Wasserman knew what she needed to do.

By this time, she was a clinical sexologist and sex therapist. She took on the pseudonym Dr. Eve and went on South Africa’s most popular black radio station to talk about sex, HIV and contraception.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

And that’s when the phone calls started. It was always men. Dr. Eve is a white woman, and she was telling them what to do in bed.

“Absolutely angry at me,” Wasserman recalls. “[They told me] ‘this is a white man’s disease. We don’t have it here in South Africa. This is not a black man’s disease. We don’t have homosexuality, and we don’t have HIV. Stop bringing your Western ideas and your Western diseases to us. We don’t have it.’”

But the reality on the ground was different. “There was these people coming forward saying, ‘I’m positive, but there isn’t anything to treat me with,’ so the deaths began,” says Wasserman.

Today, Dr. Eve is one of South Africa’s most beloved talk radio hosts.

In South Africa, people listen to the radio all the time. And radio has helped people talk about HIV.

Talking about it is important

Talk radio star Criselda Kananda Dudumashe can relate to the issues facing HIV positive South Africans. She’s HIV positive herself.

On a weekday evening at her radio station, Metro FM in Johannesburg, Dudumashe preps for her call-in show.

_1.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

“Let’s talk about sex baby,” she sings with a laugh. “Whenever I would be on any platform talking about my HIV status, you’d have people looking at you with disbelief."

Dudumashe is also one of the few media stars who have come out publicly as being HIV positive. She says she wanted to do a different kind of radio show — one that really talked about living with the virus. What to eat, how to make love, how to enjoy yourself.

How to live, really, is what 7 million HIV-positive South Africans have to figure out at this point.

“It’s exhausting,” Dudumashe admits.

The next generation of radio talkers

The township of Khayelitsha, in Cape Town, has been hit hard by the epidemic: At COSAT high school, most of the kids have a friend, a relative or a neighbor who is positive.

Some of the students are youth radio reporters who work with the Children's Radio Foundation. With guidance from instructors, the teens put together a radio show where they talk about issues that affect them.

A lot of these conversations are really similar to the ones Dr. Eve had 20 years ago. And that’s something that exasperates activists and health workers. On the one hand, everything in this country has changed dramatically. But sometimes, it seems like time has stood still. HIV is still rampant: Nearly 20 percent of the adult population is infected. And even though billions have been invested in education and access to protection, most new infections are still in young people.

Especially girls.

“What people don’t know about Khayelitsha is that it is a vibrant place, full of young people, who are very smart," says Khanyisile, a COSAT student and young reporter. "And [people] who are full of life. It is stigmatized, it is associated with crime. This is not the only thing that is associated with Khayelitsha.”

If 17-year-old Khanyisile sounds defensive, it’s because she is. These students are fatigued.

They are fed up with peers who don’t change their behavior when it comes to sexual activity. And most of all, they're tired of discussing what everyone already knows: how to make this stop.

Despite all of that, Dr. Eve goes on the air to an entire country once a week. Every weeknight, Criselda Kananda Dudumashe switches on her mic and talks to a nation. And on some days, a tiny little radio broadcast makes its way through the sprawled-out mound of corrugated metal and cement houses that is Khayelitsha.

They're all hoping the signal will come through loud and clear, and things will get better in South Africa.