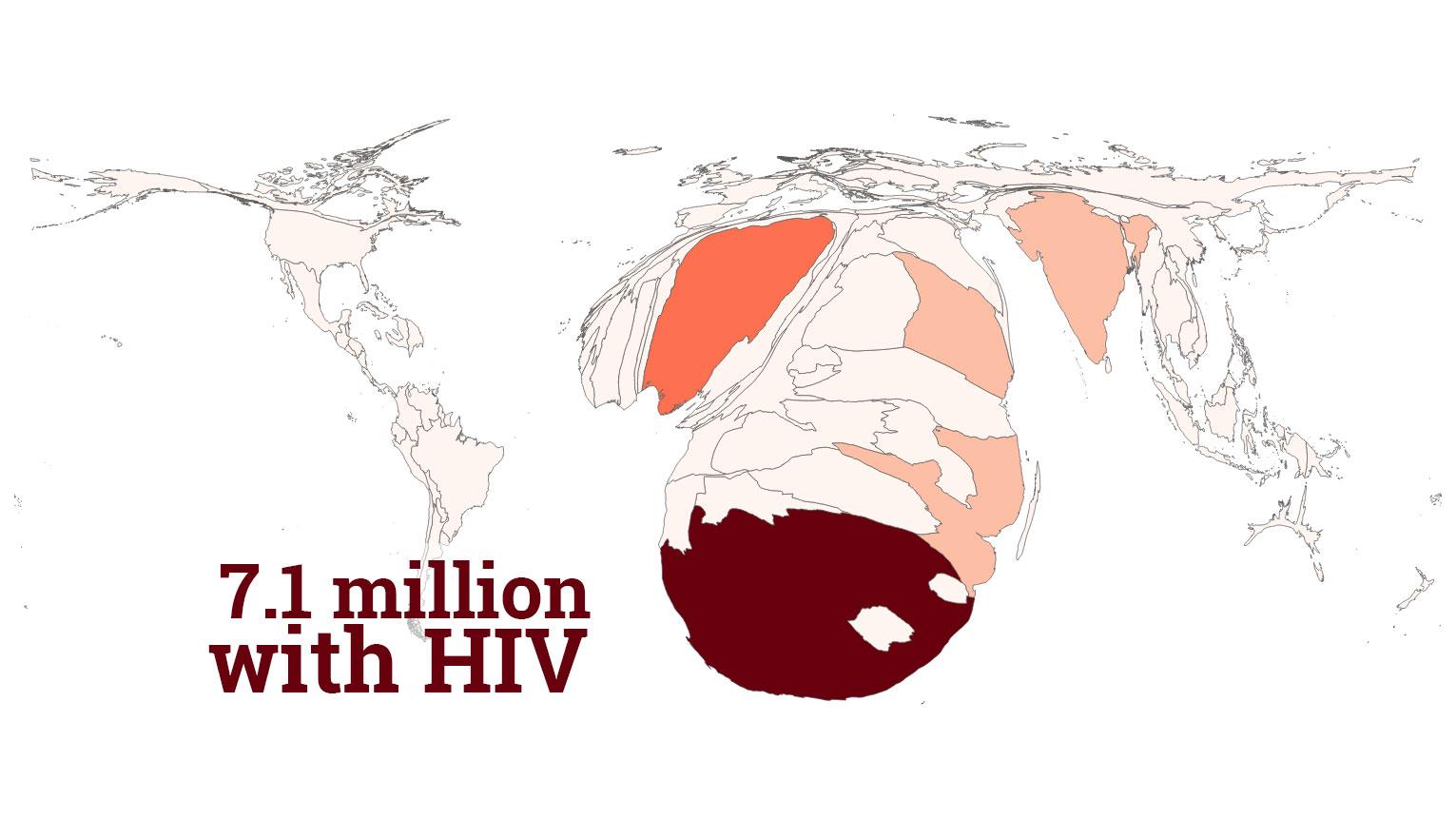

In South Africa, HIV rates are rising in young women and girls. Our new series looks at the reasons why.

Advocates say they’re winning the war against HIV/AIDs.

At the International AIDS Conference in Paris last week, officials released numbers showing improvement: New infections of children fell by half from 2010 to 2016. AIDS-related deaths have also fallen about 50 percent from their 2005 peak, when the disease killed 1.9 million people.

“This will be probably be, in history, the first pandemic that we will be able get control of without a vaccine or a cure,” says Deborah Birx, the US Global AIDS Coordinator who oversees the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

Controlling the disease requires a multi-pronged effort involving $19 billion in aid and relies on antiretroviral therapy, circumcisions and other interventions to reduce transmission and keep people healthy.

Swaziland has the highest HIV prevalence in the world at 28.8 percent. In July, officials celebrated halving Swaziland’s HIV infection rate. But in a neighboring country, for a select group of people, HIV rates are rising. Across Women’s Lives travels to South Africa to find out what’s happening for women and girls there.

‘It’s insanely wealthy’

Researchers say young women are at a greater risk because of early sexual activity and relationships with older men who are already HIV positive.

“Instead of having relationships with their age cohort, they were having relationships with men about seven to eight years older, who are already HIV positive,” Birx says. “It was the age differential that really resulted in the [higher] risk factor to young women.”

In some cases, this relationship is characterized by the use of the social hashtag #blessed. In South Africa, a “blesser” is an older, wealthier man who can “bless” a younger woman with gifts.

“The Blesser culture is nothing new,” explains Nolwazi Mkhwanazi, a medical anthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, who has studied teenage pregnancy in many communities in South Africa. “It used to be called transactional sex; it used to be called intergenerational sex.”

That intergenerational sex is a driver of HIV infections in young women. The older men often have HIV and then pass the disease on the young woman.

“These blessers are high risk men,” explains Marlene Wasserman, the host of a popular talk radio show where Wasserman answers questions as Dr. Eve. “These are men who are probably married, and they’ve got multiple partners. And they’re not using condoms.”

But the rise of smartphones and camera phones has changed the practice.

“It’s happening literally in my phone and all around me,” says Lebohang Masango, 26, who is writing a dissertation about the blesser culture. “It’s very possible that blessers were always around, but it’s just now — because of the highly narcissistic quality of Instagram — we get this insight into how these people are living.”

Masango says the use of #blessed on Instagram exploded in South Africa in December 2015. Being #blessed is similar to having a “sugar daddy,” but with differences.

“When the whole blessers thing exploded, it was about the sheer obscenity of the wealth,” Masango explains. “It was insanely wealthy. Many people are not accustomed to the levels of luxury consumption that were being displayed, especially from relatively unknown young women on social media.”

Some women who seek out blesser relationships are from South Africa's middle class and already have some money to buy clothes and makeup to attract a blesser, Masango says.

"Sandton (a wealthy neighborhood in Johannesburg) is the richest square mile in Africa," Masango says. "It has beautiful restaurants, beautiful nightclubs, a lot of the time when these relationships are solidified, it happens because they met in these areas. You have to have access to that money to begin with. You have to spend money for a blesser to look at you and say, 'I want her on my arm, I want to take her to Dubai.' "

Jokes are even made about how to tell how serious a "blesser" is. A cartoon in South Africa shows levels of blessers. A level one blesser can buy a girl phone credit; a level five blesser takes her on vacation to Dubai.

“[The blessee] wants the three C’s: she wants the cash, the credit card, and the car,” Wasserman says.

For her research, Masango has been seeking out women who defy the stereotypical blesser relationships.

“One young woman, she uses Tinder in order to meet older men,” Masango says. “She’s incredibly firm in her beliefs and very unapologetic about how she feels about being compensated for her time in romantic relationships. 'You pay for my time, you’re paying for my attentions'. She’s studying engineering so she could be studying and spending her energies on herself at a particular time so he must pay for her time and her emotional labor if she will be spending that time with him, instead. She just does this because it’s fun and she refuses to engage with men in ways that are not materially beneficial to herself. That already is a break from the dominant narrative.”

Masango says the women she has met in her research are older — in their early and mid-20s and speak responsibly about HIV prevention.

“The young women I’m studying with really [have] amazing sexual health practices,” she says. “They test before they sleep with anyone. They insist on condoms. They are the people — all of those advertisements — it reached them and it resonates and it works in their lives. They protect themselves even as they’re doing something as risky as having multiple concurrent partner sex.”

Masango’s research matches what PEPFAR has been finding.

Birx, with PEPFAR, says surveys have shown that young women know about HIV, but not all the education efforts seem to work.

“The young women had incredible knowledge about HIV, but none of them believed they were at risk for getting HIV,” she said.

Still, anthropologist Nolwani Mkhwanazi says talking about sex is a really hard thing to do in South Africa.

“Even though sex ed is part of life, life orientation, teachers, especially in rural areas, find it very difficult because of cultural ideas of who has the right to speak about sex and when,” Mkhwanazi says. “It's very different to teach sex education, including ideas around contraception. They can't get this information from nurses and hospitals either because of the same ideas.”

Another way HIV is transmitted to women is rape and South Africa is home to one of the highest rates of rape in the world. The law changed in 2007 to include a better definition of rape, which previously had only covered vaginal penetration of a woman.

"We’ve got to address the sexual violence in our country because that is really driving HIV in this country," Wasserman says. "One of the things we know is that a contributor towards men raping, is if they themselves were survivors of trauma, or victims of trauma, or if they themselves have witnessed trauma. So you’ve got people who are economically, absolutely, absolutely poverty stricken, and powerless. And so when you have that, as a foundation of men who are powerless, and not able to provide for themselves or a family, there’s a huge amount of anger that happens. And when there’s a huge amount of anger, there’s a huge amount of violence. Male on male violence is huge in this country. And it’s expanded into male on female violence."

The 90-90-90 goal

HIV officials use something called 90-90-90 or the HIV cascade to describe their plan for defeating the disease.

It’s an approach to fighting the pandemic that tries to bring down the rate of infection and, over time, eradicate the disease. The goal: 90 percent of people living with HIV know their status; 90 percent of those who know their status are on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90 percent of those on ART achieve viral suppression by 2020.

In some countries, PEPFAR and other public health groups have made massive progress toward 90-90-90 targets.

In July, PEPFAR announced that Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Zambia are nearly there.

is from a 2016 PEPFAR survey. In South Africa, 86 percent know their status; 65 percent are on ART and 56 percent on ART are virally suppressed, according to UNAIDS.

PEPFAR has funded voluntary male contraception and antiretroviral drugs. Once a person’s viral load is suppressed with ARTs, the person is likely to live a longer, healthier life, and the likelihood of transmitting HIV plummets — it can be as effective as consistent condom use.

PEPFAR was established in 2003 by President George W. Bush and was reauthorized in 2008 and again in 2009 under Barack Obama. It’s not entirely clear if funding for PEPFAR will change during the Trump administration. In April, Bush defended the program in an op-ed in the Washington Post: “Saving nearly 12 million lives is proof that PEPFAR works, and I urge our government to fully fund it,” he wrote.

Since its inception, PEPFAR reports it has prevented nearly 2 million babies from being born with HIV, supported more than 11.5 million people on ARTs and provided HIV testing and counseling to 74.3 million people.

It is unclear exactly how the Trump administration will fund PEPFAR. Unlike other agencies, PEPFAR is not specifically targeted for drastic cuts, but the budget submitted to Congress calls for big cuts — $13.5 billion to foreign aid programs like USAID, many of which contribute to PEPFAR’s bottom line — that many think will have devastating effects in Africa.

Fighting before transmission, not after

In 2012, a new drug joined the HIV fight. PrEP, which stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis, is a pill that can be taken daily (studies are underway exploring other methods of taking the drug) and can prevent the HIV virus from replicating in a person’s blood. The WHO identified the drug as a preventative tool in 2012; in 2014 the CDC began recommending its preventative use in high-risk populations.

In the United States, PrEP, usually available under the drug named Truvada, is available mostly to gay men. In 2016, drug manufacturer Gilead reported that about 79,000 people had prescriptions. Of those, 60,872 were men and 18,812 were women. Researchers said use picked up in major cities with large gay populations where advocacy groups encouraged men to use the drug. Uptake by women is still low, though.

To be sure, in the US PrEP can be quite expensive. For those without insurance, it can be $1,300 a month or more. Even for those with insurance, co-pays and deductibles can still make the drug several hundred dollars a month.

In South Africa, only sex workers are given free access to PrEP, but the government plans to expand it to young women. For now, there are a number of trials investigating different methods to administer PrEP. The current method, a once-a-day pill, is sometimes a regimen that cannot be followed, so drug companies are testing an injectable PrEP that lasts 8 weeks.

Investigators are also doing trials on a slow-release vaginal ring.

"It's a silicone ring and it's impregnated with an anti-retroviral," says Dr. Katherine Gill, a medical officer leading the trials at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation in Cape Town.

Gill says that the ring, if proven safe, could "avert at least a million HIV infections [globally] over the next 20 years."

Our series POSITIVE: The stories of young women and HIV in South Africa begins Friday with the story of one teenage girl who discovered that she was HIV positive at the same time she found out she was pregnant. Join us from Aug. 7-11 for stories about the blesser culture, PReP tests and how women are defining themselves as “HIVictors” in this battle.