The remains of a destroyed church in the town of Qaraqosh, south of Mosul, Iraq, on April 13.

Hazm Aboush welcomes visitors with a string of apologies.

He's sorry for the bareness of his home. He's sorry that he's not in better spirits, and that he cannot offer more food. He asks for forgiveness and talks about how things used to be.

“You cannot understand, they took everything,” he says, sitting in the sparse front room of his home in Qaraqosh, northern Iraq. “They took the tiles, the air conditioners. Someone even took the front door.”

Many of the houses on his street were left with less than that. Scorch marks reach out of every smashed window. Ornate outer walls of the castle-like homes are riddled with bullet holes. Even trees have been felled as a petty parting shot.

It’s the same everywhere you look throughout the town. The churches, their altars, hymn books, pews, artifacts — the things that the 50,000 former inhabitants of this Christian town held dearest — have been desecrated.

This is what ISIS extremists did to Qaraqosh during their two-year occupation, until they were chased out in December last year. The graffiti they left on the walls is a claim of ownership to the carnage.

But it’s not the actions of the fanatics that consume Aboush. It’s the alleged collaboration of the people he used to call friends and business partners — his Sunni Muslim neighbors.

“When I bump into them now, they turn their faces and walk away,” says Aboush, 60, who says his family was the first to return to the town, in March. “They know what they did. They know they’re guilty. I don’t even say hello to them.”

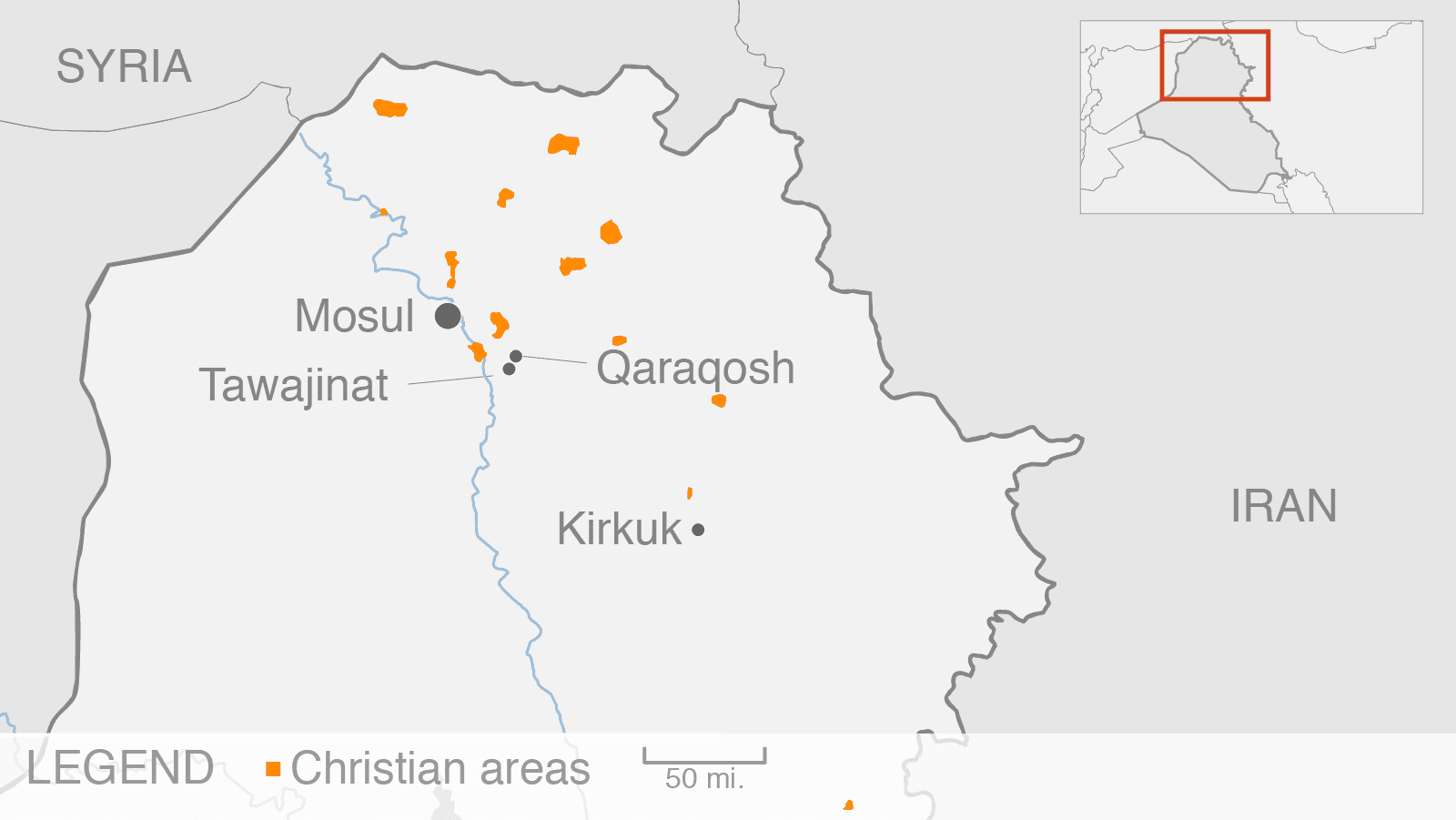

Qaraqosh lies in one of the most ancient parts of the world, in the former heart of the Assyrian Empire, close to the ruins of the ancient Assyrian cities of Nimrud and Nineveh.

The town’s Christian identity dates back to the fourth century, when Assyrians adopted the new religion and began building monasteries and churches.

Before ISIS came along, Qaraqosh was an affluent town. It drew wealth from its farmlands and from trade with the metropolis of Mosul, just 20 miles down the road.

Things became difficult for Iraqi Christians following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, which set off a wave of Islamist militancy in Mosul. Christians were targeted by extremists. Around half of the estimated population of 1.4 million Iraqi Christians fled between 2003 and the arrival of ISIS. Many left the country for the US and Europe. Others stayed, fiercely protective of their homes and their heritage. Human rights groups estimate only around 300,000 Christians remain in Iraq.

According to Aboush, the arrival of ISIS changed all that.

“Our relationship was good, there is friendship and history between us. But sadly they betrayed us, they took everything. Terrorism turns even your neighbors on you,” he says.

Aboush fled with the rest of the town when ISIS advanced in 2014. The group had made their intentions toward Christians very clear. Shortly after capturing Mosul, they announced that Christians in the area must convert, pay a special tax or “face the sword.”

ISIS carried out a vicious campaign of kidnap and murder against minorities in and around Mosul — targeting not only Christians, but Shiite Muslims and Yazidis too.

Related: Years after US Iraq intervention, Yazidis are still seeking safety on a mountain

But many Sunnis assumed they had less to fear from ISIS, so they stayed when the group came. As Aboush tells it, that’s not all they did.

“One of them told a relative of mine: ‘Don’t think about your land, it is ours now,’” Aboush recalls. “They were friends, they used to work together in the harvest. He told him: ‘Your harvest is now mine.’”

He says they welcomed ISIS. Even that many of them were ISIS.

“For two years we were displaced, we asked our Sunni neighbors who stayed behind to check our homes. They were 500 meters to 1 kilometer away, but they refused to do it,” he says.

When Aboush finally came back to Qaraqosh, he says he found many of his possessions in the homes of the Sunni villagers he used to call friends.

He brings out a picture of a chicken farm that he owned. It shows him standing proudly in the center of a large warehouse, surrounded by thousands of tiny chicks. He doesn’t know what happened to them.

The warehouse was later turned into a base for ISIS fighters. A target on one of the walls is surrounded by bullet holes. Dug into the earth inside the building is a tunnel that ISIS fighters used to hide from fighter jets.

“It’s hard, I can’t pick myself up. I had 100 million Iraqi dinars [$85,000] in this, I was a big farmer,” he says.

Aboush keeps saying it was “our neighbors” who did this. He lumps ISIS and the Sunnis into one. “Who is ISIS made up of?” he asks.

For him, Sunnis supported the Sunni militant group because they sought to gain from its dominance, at the expense of everyone else.

The Sunni village next door

The farming village of Tawajinat is just a five-minute drive away from Qaraqosh. An abandoned factory looms over it.

Talal Hassan lives in a small compound of a couple of houses and a sheep pen, just off the road that leads from Qaraqosh. He is a tribal leader, who has homes here and in Mosul. And he is one of the Sunni neighbors of whom Aboush speaks so disparagingly.

There are parts of his story that mirror Aboush’s, but the characters are flipped — the winners and losers aren’t so clear, nor are the victims.

For 40-year-old Hassan, a father of six, the problems began before ISIS came along. His story begins with the arrival of US forces and the deposing of Saddam Hussein, 14 years ago.

“It’s all the Americans’ fault,” he says. “After Saddam fell, they gave the rule to the Iranians. They put the country in the hands of the Iranians and left.”

As Hassan tells it, Iraq was handed over to the Shiites, and the smaller Sunni population suffered.

“Before ISIS came, Sunni Arabs couldn't buy anything in their name in our own areas,” he says.

The US invasion of Iraq exacerbated existing sectarian tensions fostered under Saddam Hussein’s rule. A brutal bloodletting brought the country to its knees during the US occupation.

The rise of Nouri al-Maliki, a Shiite who served as prime minister from 2006 to 2014, led to repression of Iraq’s Sunnis. He froze Sunni leaders out of power, fostering a deep resentment. Widespread protests broke out across Sunni areas in 2012-2013. Maliki responded with brutal force.

The spiral of violence would not stop. ISIS took advantage of the chaos, painting itself as a protector of Sunnis. It swept across western and northern Iraq, taking Sunni town after Sunni town, welcomed by a beleaguered population who felt as though they had been living under occupation for so many years.

“All the Sunnis welcomed them when they first came,” says Hassan. “We thought they were tribal revolutionaries. Sunnis were being oppressed by the Shias and the Kurds and the US troops that invaded the country. They came to remove the oppression from us. People welcomed them.”

It quickly became clear that ISIS was not the liberator he and others thought it was. Hassan says Sunnis were not spared ISIS’s brutality.

“After a month or two they put up the black flags, and the killings started.”

Like his Christian neighbor Aboush, Hassan was a wealthy man before ISIS came along. He had a few businesses, and made a good living. And like Aboush, he too lost everything to ISIS.

“The killings, the thefts, no work, taking women. Life stopped completely. People turned against them, but there was nothing they could do,” he says.

He says many Sunnis helped Christians when ISIS came. He says he put his own life in danger by personally helping a family escape Mosul by smuggling them in his car.

“ISIS ordered their death,” he says of one Christian family from Mosul. “I put them in my car and dressed them in women’s niqab and smuggled them out. Their money stayed with us, then they came back and took it.”

He says he has received death threats from ISIS because of his opposition to the group. Today, he fears reprisals from both the people he’s accused of collaborating with, and his Christian neighbors who see him as a traitor.

Hassan recognizes that the trust between his community and his Christian neighbors has been severely damaged. But, as he sees it, they were both part of the same tragedy.

“We say that the Christians are our brothers, if you can prove that any of us took your money or attacked you, we are ready to repay you four times. We have no one in this country we can coexist with but our Christian brothers. Remember you lived hundreds of years with the Arab Sunnis,” he says.

*****

Today, the streets of Qaraqosh are largely deserted. Soldiers clang through in beaten up trucks, and stand guard at checkpoints along the road.

A local Christian-led militia has formed. They helped recapture the town and have sworn to protect it against future attacks.

One of them is the owne of a liquor store that was ransacked by ISIS when they took the town, and is now defiantly serving stiff drinks to people fleeing the hell of Mosul.

Related: An Iraqi liquor store has quietly reopened after ISIS

More than 100,000 Christians were displaced by the ISIS invasion — most of them are still in camps or temporary homes. Aboush has been back in his home for a few months now, and about a dozen Christian families have since followed his back to Qaraqosh.

Both Aboush and Hassan are rebuilding. The removal of ISIS is not the end for either of them. Their livelihoods have been taken from them. Their homes have become graveyards, full of bad memories.

Their story is one that has played out in Iraq countless times over, and that looks set to repeat itself again. It is one in which a minority of extremists are able to turn communities against each other, and in which both ultimately lose.

Hassan, and many Sunnis, now fear for their future. He can see history repeating itself.

“You know what the Sunnis wish? They wish for the Americans to stay,” he says.

“We used to hate the American forces, we didn’t want them. But if they Americans don’t allow the country to settle down, rebuild it, and leave some power for the Sunnis, more groups will come. In two years we’ll get something other than ISIS, militias that will come and take what it wants. There is no future.”

Related: For war refugees, sanctuary in the West isn’t always a happy ending

For all his apologies, Aboush is still optimistic. What is most important to him is that Christians come home.

“I was one of the first to come back to my land, because my land is precious to me. I would never leave it. If I leave it and others leave it to who will it be left to?” he asks.

“Anyone would be sad at this situation. The town was full of people, now you see burnt homes. When you see that holy church burnt, that church built by our fathers and grandfathers, it’s hard, very hard.

“But hopefully the efforts of the locals will bring it back to life. They’re all coming back, even the ones calling us from abroad. They said as soon as services are back, we will all come back. Because there is absolutely nothing like Iraq.”

Richard Hall reported in Qaraqosh, Iraq.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?