Children play with a kite at a shelter for displaced Yazidis on Mount Sinjar, northern Iraq.

Wadha Khalaf sits cross-legged on the rough ground, throwing dough between her hands like she’s done it a million times before.

The 45-year-old mother of 13 is a new arrival among the thousands of displaced Yazidis living on top of Mount Sinjar, in northern Iraq — a sacred place for people of her faith.

But it is not the first time she has sought safety here.

Nearly three years after fleeing a murderous rampage by ISIS fighters, Khalaf is part of a wave of Yazidi families who have been forced to escape again, this time because of fighting between groups that have sworn to protect them.

“It has made me feel like we would never feel happy again in our life,” she says as she piles the bread high.

Fleeing to the mountain

This tent city on the mountain where Khalaf is taking shelter has been here since 2014, when thousands fled an ISIS invasion of dozens of towns and villages in the Sinjar region, in what the United Nations says was genocide against the Yazidi people.

ISIS kidnapped thousands of Yazidi women to use as sex slaves and killed civilians by the hundred. Nearly 4,000 Yazidi women are still being held by the militant group, according to the Women and Girls Support Center.

Those were the atrocities that prompted the United States, in August 2014, to launch its first strikes against ISIS in Iraq, opening a long campaign against the group that has extended to Syria, and been overseen by two presidents.

Related: This 84-year-old woman crawled on her knees to safety to escape ISIS

Years later, despite huge international attention for their plight, many Yazidis are still searching for safety.

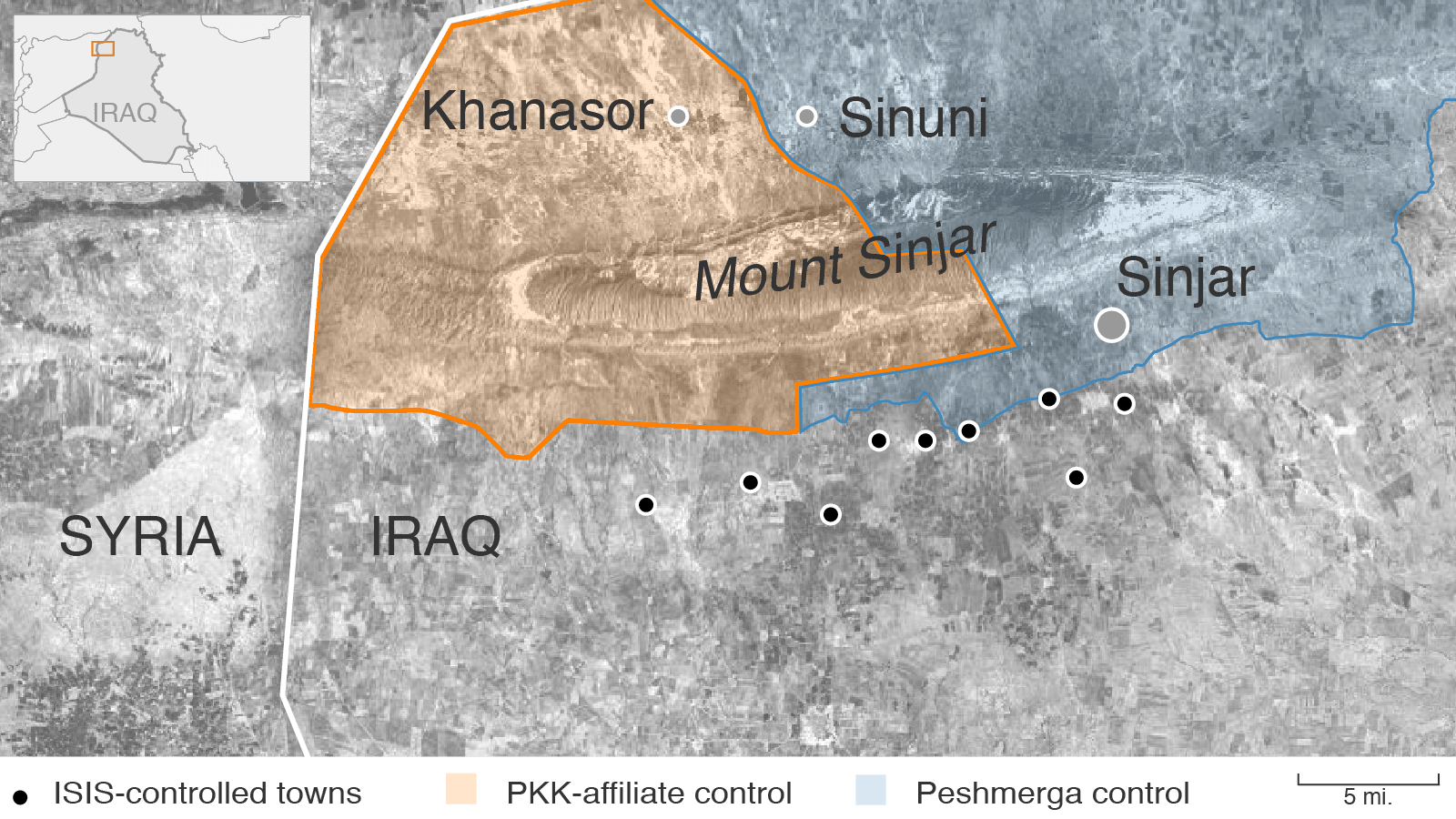

In March, long-simmering tensions between rival Kurdish groups boiled over into armed clashes in the Sinjar region.

With ISIS to the south and Kurdish infighting in the north, there is now a sense among Yazidis that they are once again trapped on Mount Sinjar. It has become both a sanctuary and a prison.

After being stranded on the mountain for nearly two weeks in 2014, Khalaf and her family made their way to a refugee camp in Syria, where they lived for two years. They later came back to the Kurdish region in northern Iraq and stayed in a relative’s house in the town of Sinuni. They were there for nine months when fighting broke out in March between Kurds in a neighboring town.

“We don’t dare to go back again. There are people getting killed in these fights,” she says. “When we got to Sinuni, we thought everything would be OK. But it is not safe there.”

A battle for influence

At the root of the fighting is a battle for influence in the Sinjar region and the presence of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK.

The PKK was founded in the late 1970s to fight for autonomy and greater rights for Turkey’s more than 20 million Kurds. It is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the US and the European Union.

More recently, it has played a key role in the fight against ISIS.

The peshmerga, the semi-autonomous Kurdish region’s official army in northern Iraq, fled as ISIS advanced in 2014. But PKK fighters based in the mountains farther north, together with their Syrian affiliates, raced to the area to support the few Yazidis who had weapons to fight. These Kurdish militants carved out an escape route that led the minority group through Syria and back into Iraq.

Many Yazidis credit the PKK and its affiliates with saving thousands of lives. The PKK has since trained Yazidi fighting groups and taken them under its banner, and stayed in the Sinjar region ever since.

The fighting in March broke out after a dispute between one of the Yazidi fighting groups operating under the PKK's umbrella and Syrian peshmerga fighters trained by the Kurdish region's president, Masoud Barzani.

Now, the Kurdish government in northern Iraq says Sinjar is secure and the PKK has no authority to stay — they should return to where they came from.

Turkey, which is allied with President Barzani's government, is adamant that they do so. The Turkish government wants to prevent the PKK from setting up a permanent base in Sinjar, from which it says the group could traffic weapons to fighters in Turkey.

In a sign of growing impatience on the matter, the Turkish air force bombed a PKK building in the foothills of Mount Sinjar on Tuesday and declared it would continue to target the group there until it leaves the area.

For the US, the fighting has highlighted precariousness of the united front it has built among anti-ISIS groups.

The US has provided significant support to the peshmerga to take on ISIS. But it has also supported the Syrian offshoot of the PKK, the People’s Protection Units or YPG. This support has strained the US relationship with Turkey, which views the PKK and its affiliates as one and the same — a terror organization on the same level as ISIS.

The US State Department expressed “deep concern” over Turkey’s airstrikes on Tuesday, but has since not taken any decisive steps to de-escalate tensions in Sinjar.

The threat of airstrikes is just another danger to add to the list for Yazidis, a religious group that’s been persecuted for centuries for its beliefs. Some of the displaced Yazidis think the PKK should leave, while others say they do not yet feel safe enough.

“If it were not for the PKK, most of the Yazidis would have been dead by the hands of ISIS,” Khalaf says. “As long as one Yazidi is in danger, we don’t want the PKK to leave. If we are given international protection and Yazidis feel safe, and the US keeps an eye on our situation, then we won’t have any problem with the PKK leaving our areas.”

Higher up the mountain road that snakes through the peaks here on Sinjar, 41-year-old Hassan Selo is putting a fence up around his tent. He recently moved here from another part of the mountain, which he has called home for the last three years.

“At the beginning, the PKK came to help us,” he says. “They brought us food, water, they aided our wounded people, they protected us from ISIS. We didn’t have military experience but they did.”

But when the situation changes, he adds, the PKK should consider leaving Sinjar.

“To say they should leave now is wrong because there is not complete safety in our area yet. But when our situation gets better and security is restored, they should leave. We are Iraqi people, they are not even Iraqis themselves. They are from other countries such as Syria and Turkey, they cannot rule here.”

No way back

In the shadow of the mountain, to the south, lies the town of Sinjar, where most of the displaced people here are from. Before ISIS arrived in 2014, it was home to some 360,000 Yazidis. Today, they are scattered in camps across northern Iraq.

For those on the mountain, stability has been elusive. There are a number of aid organizations active here providing food, water and medical care, but work opportunities are limited.

One man who got bored of waiting is Kassem, a 25-year-old from Sinjar who has set up a small shack as a barbershop by the side of the road. It’s filled with young men waiting for their turn in the chair.

Kassem, who asks that only his first name be used, says the most popular haircut in his shop is the American style, or more specifically, the American soldier style. He jokes that the man in his seat is getting an “Obama.”

“Maybe later we will we do this for Trump soon,” he says.

For Kassem, a young man with ambition, every day that passes here feels like an eternity. He says the Yazidis feel forgotten.

“The humanitarian services are very low, things such as water, tents. It is around three years that we are under these tents, I have a feeling that the international community have closed their eyes, and I don’t know why.”

Kassem learned to cut hair on the fly. He watched other people do it and just practiced. He seems like an optimistic person, but like most people on Mount Sinjar, he foresees a difficult time ahead for the Yazidis.

“We have nothing left, and there is nothing that didn’t happen to us. We as Yazidi people don’t see much safety in the Middle East. Especially with the racist ideology that is here. We hope that someday it will vanish, and we can live together peacefully.

For now, he says, “nobody can reach the mountain.”

Richard Hall reported from Mount Sinjar, Iraq.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!