Syria’s national soccer team can’t escape the country’s brutal civil war

Soccer – South Korea v Syria – World Cup 2018 Qualifiers – Seoul World Cup Stadium, Seoul, South Korea – South Korea's Kim Jin-su and Syria's Mardkian Mardek in action.

For most serious soccer players, scoring a spot on your country's national team is a dream. But what if you're playing for a country at war — a country whose president has been accused of war crimes against his own people?

After years of grisly conflict, Syria's top soccer players are facing that exact question.

The national team is vying to qualify for the World Cup in 2018. It's in the third round, which brings Syria closer to qualifying than it has been in more than 30 years. But some of the team's top players, who love their sport and their country, are boycotting Team Syria because they don't want to play for Bashar al-Assad.

“The Assad regime is essentially taking the position that the team is above politics. That it’s the one place where Syrians from all sides can come together in peace,” says Steve Fainaru, a senior writer with ESPN.

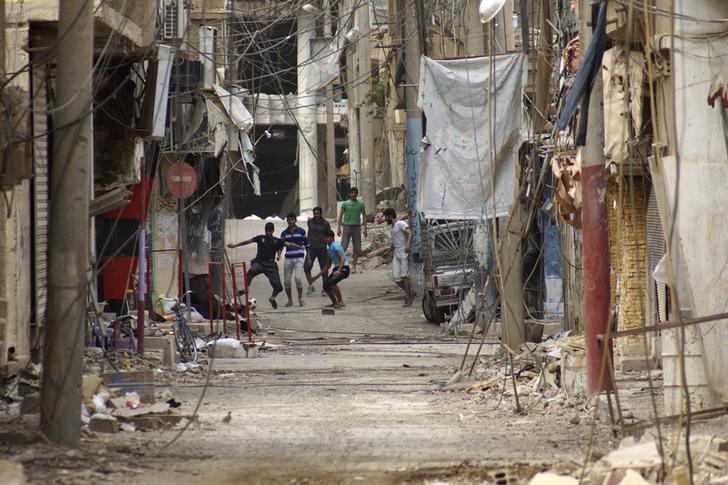

But there are claims that Assad has been using soccer stadiums as military bases, killing soccer players, and forcing players to march in support of his government. Like the civilians who are caught up in the brutal civil war, soccer players too face the dilemma of picking a side — choosing to play or not.

Fainaru and a team at ESPN recently published a full investigation into "The Dictator's Team." What follows is an excerpt of their story.

On a cool February afternoon, one of Syria's greatest soccer players sits outside a mall on the Persian Gulf, paralyzed by a decision that he fears could kill him.

For five years, Firas al-Khatib has boycotted the Syrian national team to protest dictator Bashar al-Assad, who bombed and starved Khatib's hometown.

Now, suddenly, Khatib seems to be having a change of heart. He is thinking about rejoining Syria for its final push to qualify for next year's World Cup. His reasons are complicated, and he's reluctant to express them.

"I'm afraid, I'm afraid," he says in stilted English. "In Syria now, if you talk, somebody will kill you — for what you talk, for what you think. Not for what you do. They will kill you for what you think."

"I'm afraid, I'm afraid," he says in stilted English. "In Syria now, if you talk, somebody will kill you — for what you talk, for what you think. Not for what you do. They will kill you for what you think."

Khatib is bearded and runty, with curly brown hair and kind eyes. He has earned millions playing professionally in Kuwait. The mall's posh setting offers a glimpse into his comfortable life here — yachts bobbing on scalloped blue water, robed men and women drawing flavored tobacco from tableside water pipes. But Khatib seems nearly crushed by the weight of his dilemma, which he discusses over two days of interviews.

"Every day before I sleep, maybe one hour, two hours, just thinking about this decision," he says.

Khatib pulls out his phone to show his Facebook page, which receives a hundred messages a day. Even some of his closest friends are ready to turn on him. One player he grew up with, Nihad Saadeddine, says if Khatib returns to Syria he'll be relegated to "the garbage bin of history along with everyone who supports the criminal Bashar al-Assad." Saadeddine vows never to speak to Khatib again.

Sometime within the next 36 days, when Syria plays its next match, Khatib must choose between two great evils that plague the modern world.

If he rejoins Syria, he will be team captain and the most important player in his country's quest to make the World Cup for the first time. He will also represent a government that — along with nerve gas, torture, rape, starvation and the bombing of civilians — has used soccer as a weapon to promote its murderous rule.

If he continues his boycott, he'll be aligned with a complicated movement that began with peaceful demonstrations and has since splintered to include al-Qaida and ISIS. ISIS has used soccer as a backdrop for some of its most heinous crimes, including the 2015 bombings at the Stade de France and a 2016 bombing at a youth soccer match in Iraq that killed 29 children.

"Now, in Syria, many killers, not just one or two," Khatib says. "And I hate all of them."

He's at a loss.

"Whatever happen, 12 million Syrians will love me," he says. "Other 12 million will want to kill me."

"Whatever happen, 12 million Syrians will love me," he says. "Other 12 million will want to kill me."

Syria's improbable World Cup bid has pitted player against player, coach against coach — divisions that mirror the conflict that is remaking much of the world. During six years of civil war, at least 470,000 Syrians have died, and life expectancy in the country has dropped from 70 years to 55. Representing a nation with more than 12 million displaced people — roughly half the population — the national soccer team is yet another battleground between the followers and opponents of Bashar al-Assad.

The Syrian government contends that soccer is the one place where Syrians of all sides can come together in peace. Soccer is "a dream that brings people together. It gives people a smile and helps them forget the smell of destruction and death," says Bashar Mohammad, the Syrian national team's spokesman.

In reality, the Assad regime — backed by FIFA's tacit support — has woven soccer into its grisly campaign of state-sponsored oppression, a seven-month investigation by Outside the Lines and ESPN The Magazine shows.

The Syrian government has shot, bombed or tortured to death at least 38 players from the top two divisions of the Syrian professional leagues and dozens more from lower divisions, according to information compiled by Anas Ammo, a former sports writer from Aleppo who tracks human rights abuses involving Syrian athletes. At least 13 players are missing. Although opposition forces have killed soccer players on a smaller scale — Ammo attributes four such deaths to ISIS — the Syrian Network for Human Rights concluded that the Assad government has "used athletes and sporting activities to support … its brutal oppressive practices."

Soccer stadiums have been used as military bases to launch attacks on civilians. From the beginning of the war, according to players, teams were essentially forced to march in support of Assad, sometimes carrying banners and wearing T-shirts with the president's image.

"Assad was keen to show people that athletes and artists were strongly supporting him because those are the people with the most influence in the street," Ammo says. "The marches were obligatory."

"Assad was keen to show people that athletes and artists were strongly supporting him because those are the people with the most influence in the street," Ammo says. "The marches were obligatory."

The ESPN investigation drew upon interviews with current and former players, current and former Syrian soccer officials, and friends and relatives of victims, as well as reviews of case studies and publicly available videos confirmed by human rights monitors. The interviews took place between September 2016 and March 2017 in Malaysia, Germany, Turkey, Sweden, Kuwait and South Korea.

This story has been updated from an earlier version.