Canadian groups are lashing out about Muslim prayer in schools

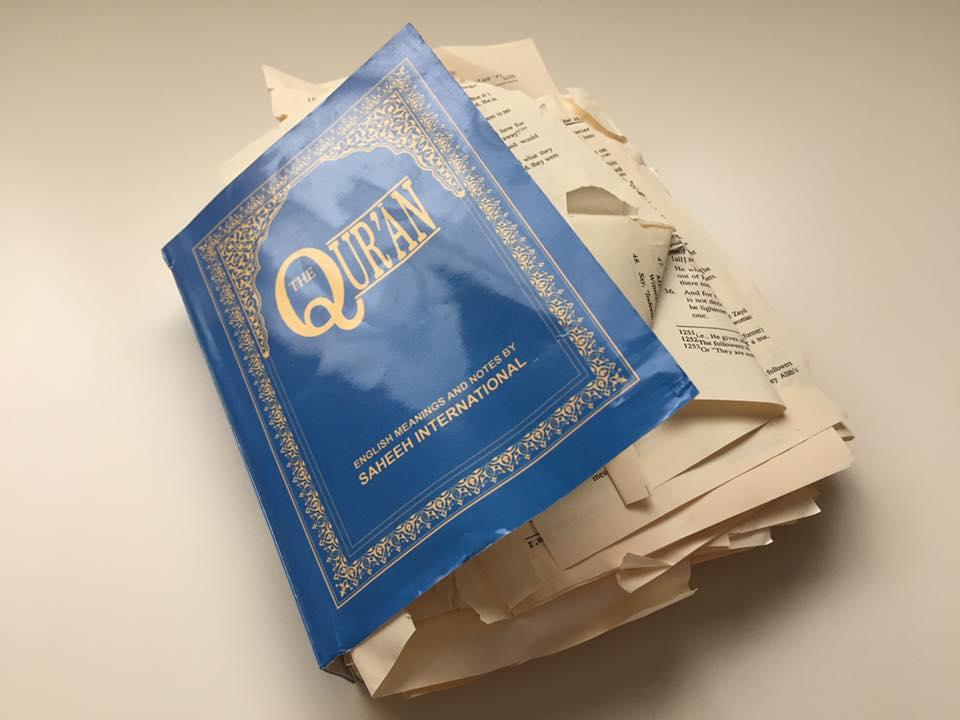

An anti-Muslim activist tore out pages of this Quran during a public school board meeting in Peel, Ontario, in March. A local imam said he posted this photo to his Facebook page shortly before burying the book.

Threats of burning down a mosque, a torn-up Quran, protests against supposed Muslim indoctrination — these are just some of the incidents in a community in Canada that make Shireen Ahmed fear for her children’s safety.

What started as a conversation about prayers last September flared into bitter arguments and protests among residents of the Peel region, just west of Toronto.

On one side, Muslim students want to be able to pray at school, which they’ve long been allowed to do under Ontario law. On the other, groups of residents say religion has no place in Canadian schools — but some activists are incensed about Islamic prayer, in particular.

During a Peel school board meeting in March, one person even tore up a Quran and reportedly stomped on it, while another man called Islamic text “poison” and told Muslims to “get out.”

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DDVIEfU3eOSk

These are of some of the latest instances that are testing the image of inclusion and harmony that Canada has projected lately. When Syrians fleeing war were turned away elsewhere, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau greeted them at the airport with winter coats. When President Donald Trump banned refugees, Trudeau again said Canada would welcome them, tweeting, “Diversity is our strength.”

But lately, Ahmed, 40, a writer and sports activist, says the harmony is not so evident.

“Is there a heightened sense of anxiety among residents? I’d say yes, absolutely. Is there a tension, a nervousness of Muslims in the community? Absolutely,” she says.

Ahmed is especially concerned for her 15-year-old daughter. She took her to self-defense courses before her daughter started wearing a headscarf, a hijab, a couple of years ago.

Ahmed is less afraid for her tall and athletic 17-year-old son, but she still worries he could find unwanted attention.

“He has a scruffy beard, he has a name that is identifiably Muslim, he’s a brown kid, so immediately he’s racialized,” she says.

Right to pray in school

The mix of religion and public education has long been a prickly topic.

Ontario provincial law requires schools to accommodate students’ religion. “Education providers are responsible for accommodating creed-related needs to the point of undue hardship,” the Ontario Human Rights Commission said in a statement in March.

Schools in Peel have been providing Muslim students a space for Friday prayers for 20 years. The school board stresses that it is not promoting or teaching any religion.

But debate in Peel broke out this year over how to supervise student prayer time. When the school board tried to introduce tighter monitoring of prayer selection, some Muslim students complained of feeling under suspicion by education officials and said they want the freedom to use whatever verses they choose.

Some opponents of religious accomodation insist they are not targeting Islam.

Ram Subrahmanian, of the group Keep Religion Out Of Our Public Schools or KROOPS, says he is against all religious practice at schools.

“You cannot expect the public system to meet the requirements of your religion. As Canadians, we are secular, we are accepting and we are tolerant but that doesn’t mean that we will allow others to impose themselves on us,” says Subrahmanian, whose youngest child is in the last year of high school in Peel.

"As Canadians, we are secular, we are accepting and we are tolerant but that doesn’t mean that we will allow others to impose themselves on us."

He says his group will take the school board to court because he believes prayers at school are unconstitutional and the board can’t speak on matters of religion in schools.

Another group at the demonstrations, the Concerned Parents of Canada, echoed KROOPS sentiment in an emailed response, stating that religious practices segregate students.

In a statement, the school board said it is following Ontario’s religious accommodation rules and criticized the Islamophobic tones of the campaign.

“We are also appalled as a board by the anti-Muslim rhetoric and prejudice we have seen on social media, read in emails, and heard first-hand at our board meetings. It has caused some of our students to feel unsafe, to feel targeted,” the statement said.

One group that does say it is specifically against Islam is Rise Canada.

“We’re against any prayers, but of course it’s worse if it’s Islamic prayers … Islam is clearly a violent, misogynistic ideology,” says Ron Banerjee, an adviser to the group. Banerjee spoke at a Peel school board meeting even though he does not live in the area.

In April, an imam who supported students during the prayer debate posted on Facebook that he received death threats, as well as threats to burn down his mosque in Mississauga.

Such threats are especially worrisome considering that, just three months before, six people were shot dead at a mosque in Quebec, allegedly by an extremist who supported President Trump and French nationalist Marine Le Pen. A Go Fund Me page is now online raising money for more security at the Mississauga mosque.

Muslim leaders say Islamophobia has been a serious problem in Canada years before the debate over prayers at school — and is on the rise.

A map by the National Council of Canadian Muslims showing reported anti-Muslim incidents details 12 cases in 2013 and 29 in just the first four months of 2017, although it is hard to know whether the increase is partly due to more people reporting hate crimes.

Islamophobia and racism are not new in Canada, says Sabreena Ghaffar-Siddiqui, a PhD candidate at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, who is researching the experiences of Muslims in Canada.

“The only new thing is that people are feeling a bit more comfortable” with public displays of hate, says Ghaffar-Siddiqui, who lives in Peel. “We’ve always had a level of political correctness in Canada where people tend not to say what they really feel.”

Although not the only factor, recent political discourse — by anyone from President Trump to Canadian nationalists, to far-right Islamophobes worldwide — is partly to blame for enabling people to go public with their prejudices, according to the researcher.

“They feel supported in their views. So now they are coming out and saying what they’ve been probably feeling for a while,” Ghaffar-Siddiqui says. “When you have people in positions of leadership” who single out minorities negatively, she adds, “You’ll get people following and it encourages them, it makes them feel emboldened, empowered.”

Tip line for 'barbaric cultural practices'

During Canada’s 2015 election, then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper campaigned to force women to remove their face-covering niqabs during citizenship ceremonies, as well as to set up a tip line for “barbaric cultural practices.”

Conservative Party leadership candidate Kellie Leitch has suggested immigrant applicants be screened for “anti-Canadian values.”

In March, Leitch attended a Keep Religion Out Of Our Public Schools event, where Banerjee spoke out about what he claimed was Islamic indoctrination and "Sharia-creep," moments before she entered. Leitch’s spokesperson said she did not know he would be there and that Leitch was supporting secularism at public schools.

“They’re really not even debates, they’re simply Islamophobia. It’s anti-Muslim sentiment … couched in a concern about religion in schools,” says Amira Elghawaby, the communications director for the National Council of Canadian Muslims.

“It’s anti-Muslim sentiment … couched in a concern about religion in schools.”

Several of the people interviewed for this story downplayed another factor reportedly at play: that rival South Asian immigrant groups are reviving old conflicts here in Canada.

Banerjee identifies proudly as Hindu and says his religious group is sensitive to issues involving Muslims. He says when rallies against Islamic prayer in school began, mostly South Asian immigrant community members attended. But then the Rise Canada campaigners brought out non-Hindu whites in large numbers.

“It would be disheartening if indeed people are bringing any sort of baggage from their own maybe experiences in another country to this debate. That would be unfortunate,” says Elghawaby.

Ahmed, who has four children, says the debate is exacerbating tension and fears that were already here.

“So many of these young kids are being targeted for their race and their religion,” Ahmed says. “To target children in this way was so not okay. They don’t have the tools to be able to defend themselves.”

Journalist Kristina Jovanovski reported in Toronto.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?