As immigration detention soars, 2.3 million people are also regularly checking in with immigration agents

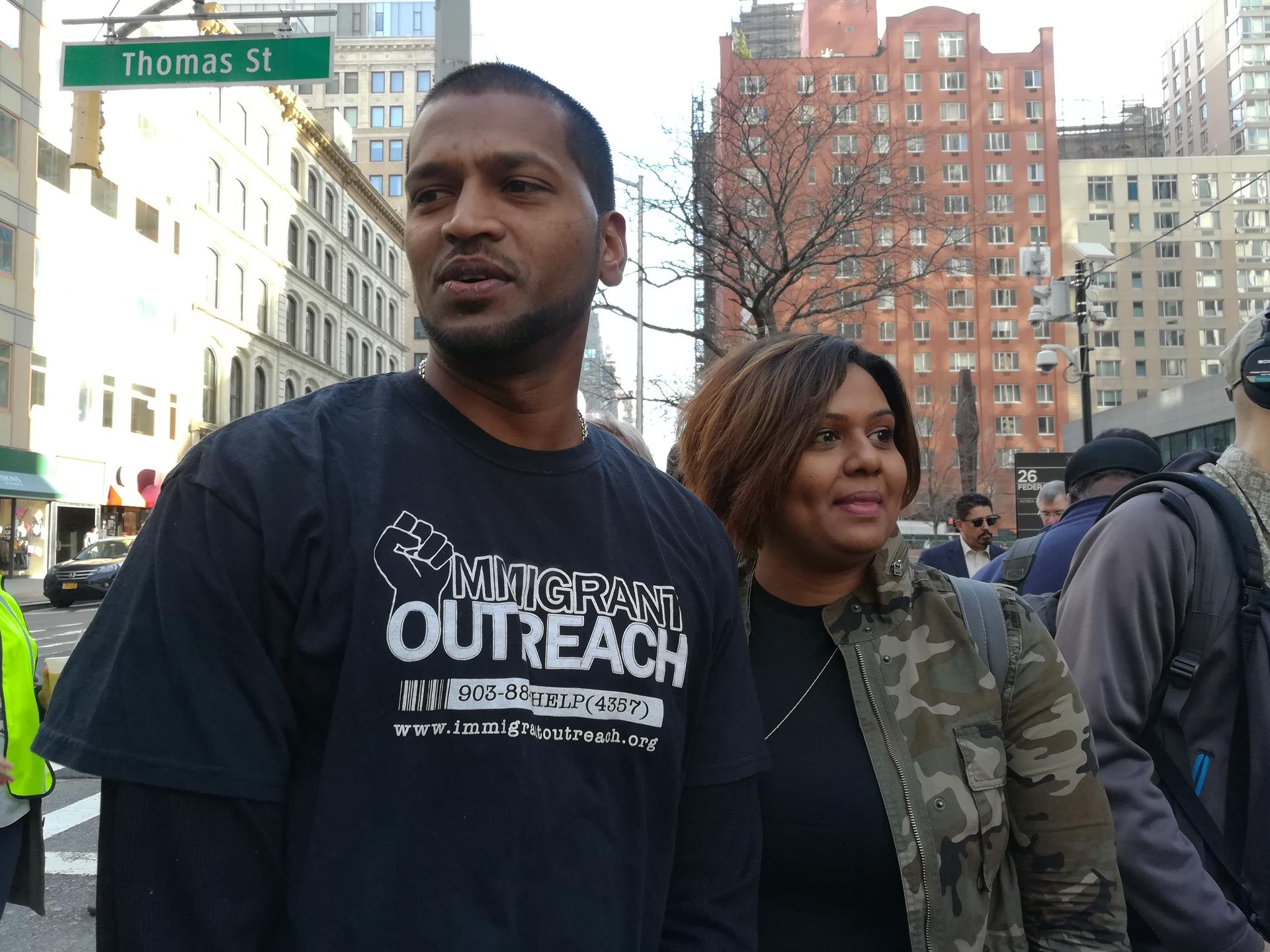

Ramesh Palaniandi, a 38-year-old legal permanent resident, walks out of his appointment on April 24, 2017, with deportation officers at 26 Federal Plaza, in New York City. He has been checking in monthly since September 2016.

Millions of immigrants in the US are under some sort of supervision by the Department of Homeland Security.

They regularly report to deportation officers about updates to their immigration court cases, the status of their foreign passports, perhaps a changes of address. Sometimes they have nothing to report. Sometimes they are told to wear ankle monitors so the federal government can track their whereabouts.

To be precise, 2.3 million people are in this system, almost 2 million of them have no criminal record. That’s the number according to a spokesperson for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in New York City. It’s consistent with a report issued in April by the Office of the Inspector General at the Department of Homeland Security. (For comparison, about 4.5 million people were on probation or parole in the criminal justice system in 2015.)

Of the 2.3 million people, 1.4 million do not yet know if they will be deported and are awaiting the outcomes of their cases.

ICE reported last week that they have arrested 41,000 people in 100 days, a 38 percent increase over the number of arrests this time last year. More people are being held in detention centers, while others are placed on the so-called “non-detained docket,” and are monitored by the agency via programs like check-ins, often for extended periods of time.

These are people in limbo, as they await decisions from an immigration system plagued by delays. And for many immigrants, it creates very personal — and fairly mundane — questions about moving forward in life.

“When can I ever have kids?” asks 35-year-old Janice Hoseine.

Hoseine’s husband, Ramesh Palaniandi, 38, has been reporting monthly to the federal immigration field office in New York City since he was released from an upstate prison last summer. He is in the midst of a years-long battle to challenge his deportation in courts.

“It’s just like — it’s traumatic, mentally, physically,” she says. “This is not life, this is not the way life should be.”

Hoseine and Palaniandi are both immigrants. She is a naturalized US citizen from Trinidad and he came with a green card, as a legal permanent resident from Guyana at age 13. Despite their legal standing, they’ve had their share of trouble. Immigration agents paid them a surprise visit less than two weeks after they bought their first home in 2015.

That’s when their American dream soured, they say.

The story began this way: In 2008, before they got married, Palaniandi served six months of a longer sentence for attempted burglary. He pled guilty to the crime on his lawyer’s advice, paid the price for his actions and moved on.

“I was ready to start my life over 10 years ago,” he says. “I changed my ways, I started all over.”

Hoseine was his high school sweetheart, and he always wanted to start a family with her.

Immigrants with criminal convictions — even if they have green cards — can be ordered removed by the government. After he got out of jail, Palaniandi’s lawyer told him that if he didn’t hear from immigration agents after one year, he would not be deported. After that year, Palaniandi thought he was in the clear and married Hoseine. They wanted to be legally and financially secure before they had children.

A few years later, when they bought their first home, they thought they were ready.

On March 2, 2015, ICE agents surrounded the couple’s house in Ozone Park, Queens, and took Palaniandi into custody. Palaniandi says the officers offered no warrant or explanation for his arrest. They told him to leave his wedding ring behind and bring $20 for a train ride home that evening.

Instead, he spent 18 months in a detention center in Orange County, about two hours north of New York City.

PRI reached out to ICE for comment, but the agency said it could not provide information on this specific case.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3Dw2fUjf4u9MM

A video released on March 9, 2015 by the Department of Homeland Security about the arrest of 2,059 immigrants over five days. Immigration and Customs Enforcement director Sarah R. Saldaña said, “These are the worst of the worst criminals.”

Palaniandi was one of 2,059 immigrants detained across the US as part of an annual enforcement operation that lasted five days. It was called “Operation Cross Check” and many of those arrested had multiple convictions. ICE said then that they were successful in detaining “convicted criminal aliens who pose the greatest risk to our public safety.” They said that the operation was consistent with President Barack Obama’s priorities for immigration enforcement.

Two weeks later, Palaniandi had an immigration court hearing. The judge told him that back in 2008 the government had retained the right to reopen his case at will. They were using his old conviction as grounds for deportation in 2015.

“I felt like Ramesh was part of a quota that had to be met,” says Hoseine. At the time, the Obama administration was under pressure to show that it could be tough on immigration enforcement, even as it implemented DACA, a program to give temporary status to undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children.

As so often happens, life went on while Palaniandi was in immigration detention. His grandfather, who brought him to the US as a child, passed away. Palaniandi was not allowed to attend the funeral.

“It was hard, because he was my role model,” he says. “I looked up to him. My father was there too, but he wasn’t one to show love.”

The months of separation were difficult. Hoseine almost lost their house because she couldn’t make mortgage payments. She makes less money as an independent graphic designer than Palaniandi does as a plumber licensed to work on large projects. (Ironically, he worked on one of the buildings where he now checks in with immigration agents regularly.)

They had taken out home improvement loans as well, but that money went instead to cover legal and medical expenses. Palaniandi needed medications not provided by the detention center for a recurring parasitic infection that resurfaced while he was incarcerated.

He was released on September 9, 2016.

“I didn’t know why [he was released], but I was happy,” says Hosiene. Palaniandi was given an ankle monitor, an alternative to detention that the federal government seemed to be using more often. “We couldn’t care less. He was coming home.”

Palaniandi says it wasn’t easy to be in detention. But it hasn’t been easy being released either.

“I can’t sleep good at night,” he says, though he is still a legal permanent resident. “I’m in fear that they’re going to knock on my door again.”

The government issued a final order of deportation against him, which he is challenging. Because of an agreement between the US government and the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, people who are challenging their deportations in that jurisdiction, which includes the state of New York, cannot be deported while their request to block the removal is pending. But that doesn’t stop immigration agents from detaining people.

On March 9, 2017, Palaniandi went to another regular check-in with federal authorities. He was still wearing the ankle monitor, but agents detained him once more.

Hoseine was shocked that the government was taking him away again. “They thought that he didn’t have a pending case,” she says.

Palaniandi spent a month in the Bergen County Jail, a New Jersey prison that contracts with federal immigration authorities to detain immigrants. While he was there, he signed loan modification papers that allowed Hoseine to keep their house.

Also: Here's how one New Yorker is helping immigrants — himself included — with government check-ins

On April 24, though, they appeared again for Palaniandi's 10 a.m. appointment at 26 Federal Plaza. Half an hour later, they walked out together. The meeting was brief, only a few minutes, says Palaniandi, and he was told that things looked good.

“Right now, we’re back on track,” he says, “but after they put me in detention in March I was like, ‘Not again, not again!’”

According to Palaniandi, he should be protected from deportation for the duration of his legal case. His next appointment is on May 24.

The budget DHS submitted to Congress this fiscal year estimates that ICE’s staff monitors 53,000 immigrants on an average day, and that is just in “alternatives to detention.” It’s a program that was created to track people with either ankle monitors, like Palaniandi had, or phone calls.

According to the New York ICE spokesperson, Rachael Yong Yow, the agency’s Enforcement and Removals Operation arm “currently employs approximately 6,000 officers who are responsible for many functions including arrest, detention management, oversight of those who are not detained and effecting deportations from the US.”

But the April report issued by the Inspector General says ICE is understaffed and overworked.

“ICE has not clearly and widely communicated Department of Homeland Security deportation priorities to Deportation Officers; not issued up-to-date, comprehensive, and accessible procedures; and not provided sufficient training,” the report reads.

Such conditions might be adding to the unpredictability that Palaniandi, and millions like him, are experiencing.

The Trump administration has further expanded the priorities for enforcement to anyone who is in the country either illegally or has “committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense,” according to an executive order issued in January.

ICE spokesperson Yong Yow said in a statement that the agency “remains committed to implementing safeguards to ensure that its deportation operations are executed in a way that promotes public safety and protects our communities.”

The agency has agreed to improve its operations as recommended by the Inspector General. Trump’s executive order calls for the hiring of an additional 10,000 immigration officers and that should help, Yong Yow says.

Avideh Moussavian, a senior policy attorney at the National Immigration Law Center, in Washington D.C., says that there has been a lack of transparency in immigration enforcement priorities in the Trump administration.

“The administration seems to intentionally want to sow confusion and fear,” she says via email. “It has a very destabilizing effect.”

“People who previously were asked to check in once every several months or year, now are being asked to check in much more frequently, even when their circumstances haven't changed,” she says. “That poses practical challenges for people who essentially lose a day of work, wages, school and creates deep fear and a terrible sense of uncertainty. It seems that ICE wants to make life as painful as possible in a way that disrupts the stability and well-being of our communities.”

And that’s how Palaniandi and Hoseine feel. The anxiety of not knowing each month what federal agents will do makes it hard to have a life, let alone plan for a future. They don’t know if having children is still an option.

“It really did some damage,” says Hoseine. She became a US citizen while she was fighting for her husband’s release in 2015. She realized that to help him, she had to protect herself first.

The couple has had lawyers in the past, but they are now representing themselves. It will save money, and they think the result will be better. But that’s making it hard for Hoseine to have time to keep working, and impossible to even consider having children.

“I wanted to start a family,” says Palaniandi, “but I have to put it all aside, because I don’t know. I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

“How can I deal with the idea of being pregnant and going through this process?” says Hoseine. “The stress on my body, the stress on the child, the possibility of being removed.”

For now, she says, it’s wiser to take it one day at a time.

One thing they’re sure of: They will not leave the US. They thought about it, but their whole life, their memories and their loved ones are here. They want to stay and help others trapped in limbo. Palaniandi met many people in immigration detention and Hoseine met their spouses and families.

They want to share what they know about the immigration system with people who are having problems.

“It’s bad that people had to wait until this administration to see what’s going on out there,” she says. “People have been receptive and we’re not going to stop.”

See full documents, including budgets and the Inspector General report, about ICE’s supervision program. With additional reporting by Angilee Shah.