In the age of Trump, fewer lenders want to provide this med student with student loans

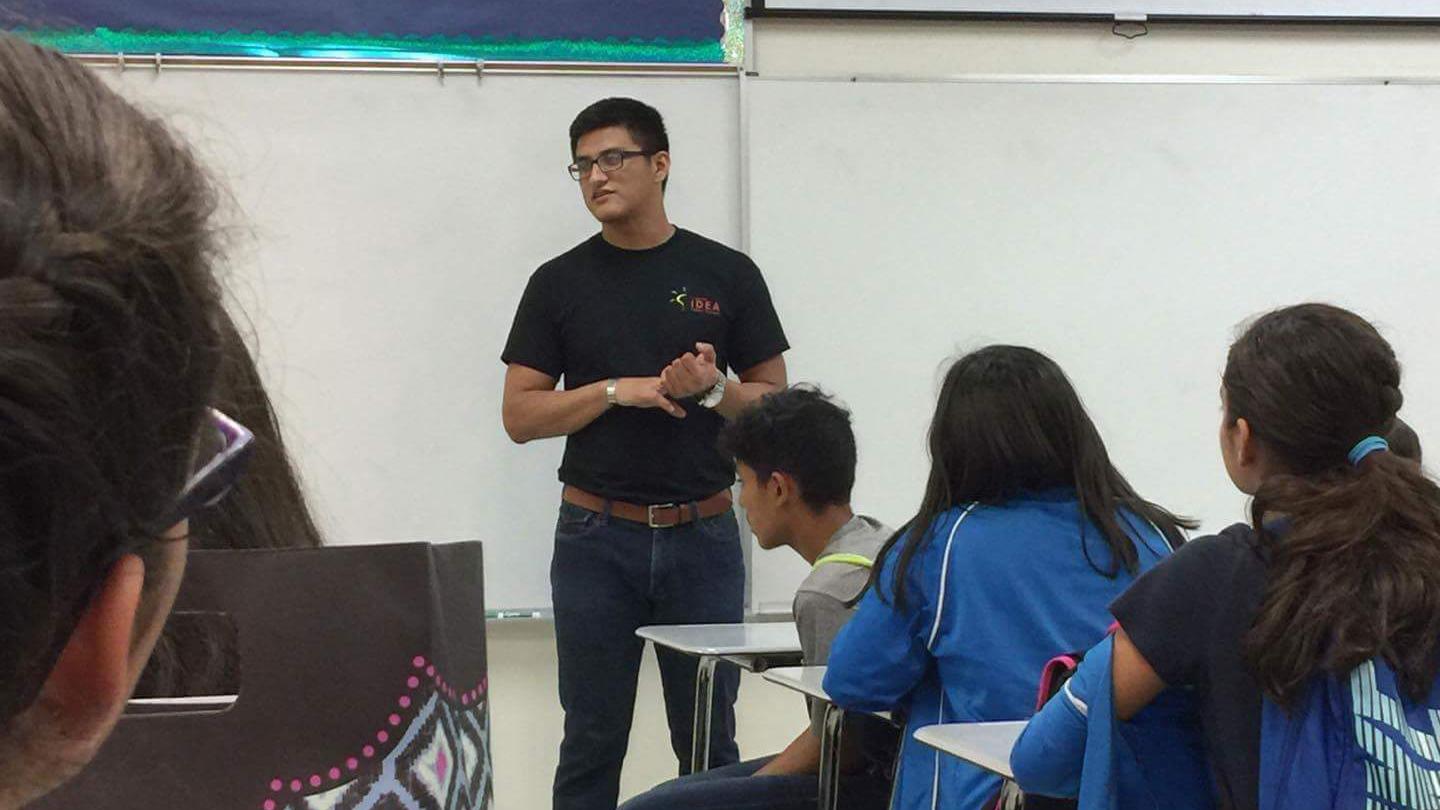

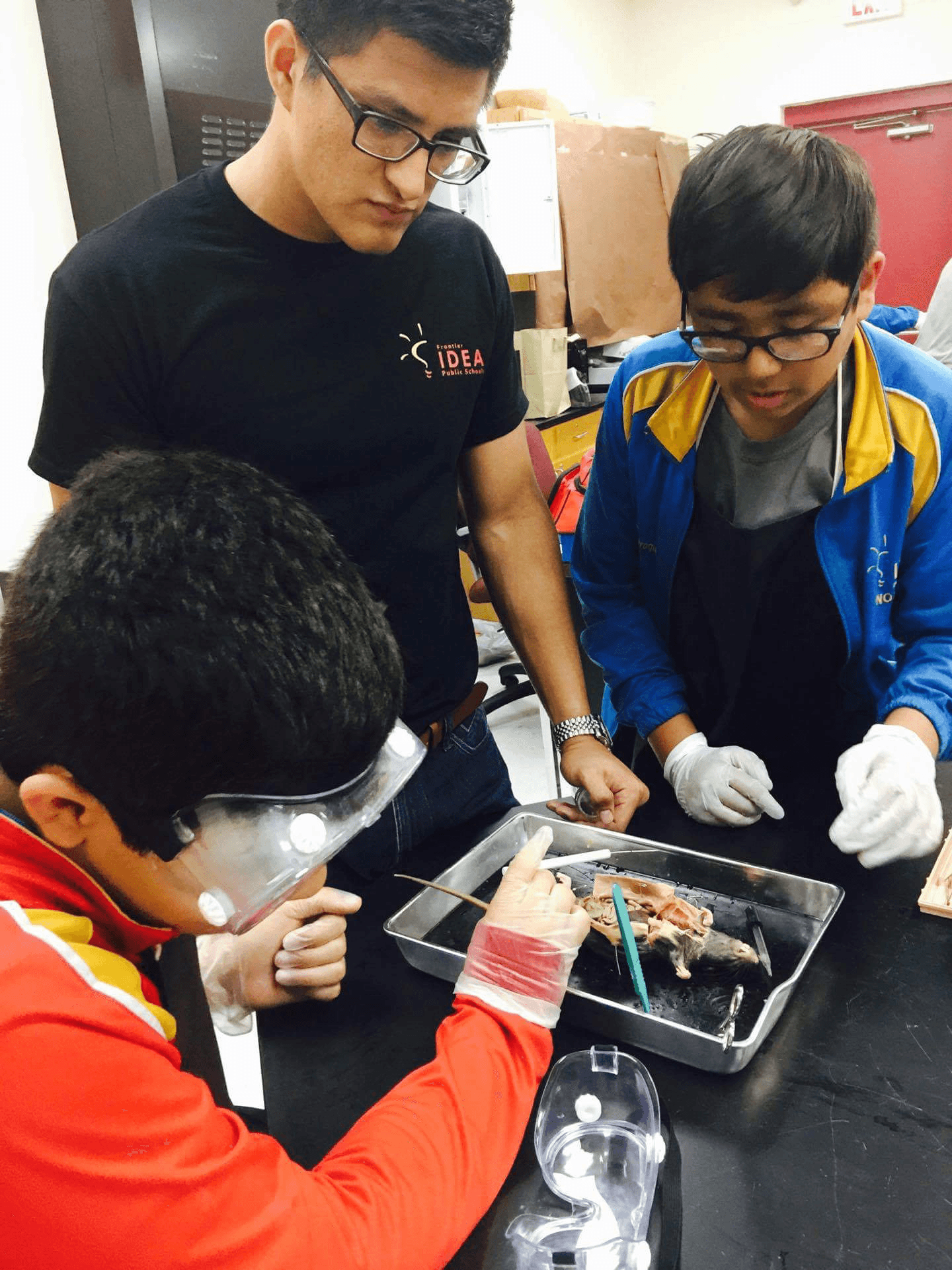

Julio Ramos is a teacher in south Texas who has wanted to be a doctor since he was 12 years old and saw his mother being treated for breast cancer.

Roughly 11,300 people applied to Loyola’s Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago this year. They interviewed about 600 people. About 160 were accepted — the odds of getting in were less than 2 percent.

And 10 of the students they accepted are undocumented, brought to the US as children. They have DACA status, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which gives them a temporary work permit and a chance to become physicians.

One of them is Julio Ramos.

“I got a call from Dr. Nakae, who I love. She’s an advocate for social justice and for undocumented students,” says Ramos. He was in.

But Dr. Sunny Nakae, assistant dean of admissions and recruitment at Loyola’s medical school, gave him unexpected advice: She suggested he attend Mount Sinai in New York City instead. They could better help him pay for school.

Most medical students pay for their studies by applying for federal student loans, which DACA recipients are not eligible for. The cost of tuition at Loyola is about $30,000 a semester, and that doesn’t include living expenses.

In the past, Loyola has collaborated with private lenders and foundations to help fund their DACA students’ education with loans. As immigration policies shift, the lenders have told the school they can’t be sure their investments will pay off. If the Trump administration ends the DACA program, students like Ramos will no longer have work authorization, which means they could not practice medicine. To lenders, this means they might be unable to repay their loans.

“They saw these students as investments in underserved communities,” says Mark Kuczewski, chair of the department of medical education at Loyola. “Unless they can be relatively assured that the student will be able to go on and practice and get licensed, which requires the work permit that comes with DACA, it’s hard for these nonprofits to use their community investment funds in this way.”

Several weeks after the first call, Ramos received an email from Loyola reiterating what Nakae had told him.

“I had to send a personal message to each of our DACA recipients who were accepted in this cycle, letting them know that we currently do not have funding options in place and that they needed to pursue their own private loans and work on assembling their own new packages for this year,” says Nakae. “We would let them defer if they weren’t able to put together the funding.”

For the last three years, the school and its partners have provided a combinations of loans and scholarships for seven to 14 undocumented students in each class.

Kuczewski says other medical school usually only accept one or two DACA students through scholarship programs. Loyola has been able to bring in more DACA students by adding private lenders to the mix.

Also: College 'dreamers' are unrelenting in fight for immigration reform

Nakae says even medical schools that are able to fund their DACA students through institutional loans, grants or scholarships are concerned about what the Trump administration will do. Students also need to complete a residency — in which a hospital employs them — in order to become licensed physicians. And there are no guarantees hospitals will be willing to do that.

Kuczewski and Nakae are also coming up with a back-up plan to fund their current DACA students, whose loans might be in jeopardy if the Trump administration terminates the program. They are also looking for support for scholarships to help fund newly admitted DACA students.

“We’re working to explore other options with other foundations and moving more towards a philanthropic type thing rather than a loan-based program,” says Nakae.

Five of the 10 undocumented students who were admitted to Loyola this year decided to go elsewhere. One partner might be able to help with tuition for two students, says Kuczewski, but the school so far cannot help the others. But he doesn't want the uncertainty to dictate students’ futures.

“It would be terrible if 10 years from now we looked back and the administration never did anything to the students [who are] DACA recipients, but we all stopped making opportunities,” says Kuczewski.

In the meantime, Ramos has decided to attend the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City this fall. The medical school awarded him a combination of loans and scholarships to pay for his medical education. He’ll finish his last year of teaching later this month and then go back to being a student.

And he’s trying to figure out how his undocumented parents can see him at a white coat ceremony this September in New York. It’s a welcome ceremony for first-year students who commit to caring for patients. Ramos’ parents are worried that if they travel past border patrol checkpoints in Texas, they could be detained and deported.

Follow: We're keeping up with Julio Ramos as he navigates his life in the Trump administration.