Brexit: The end of a loveless marriage

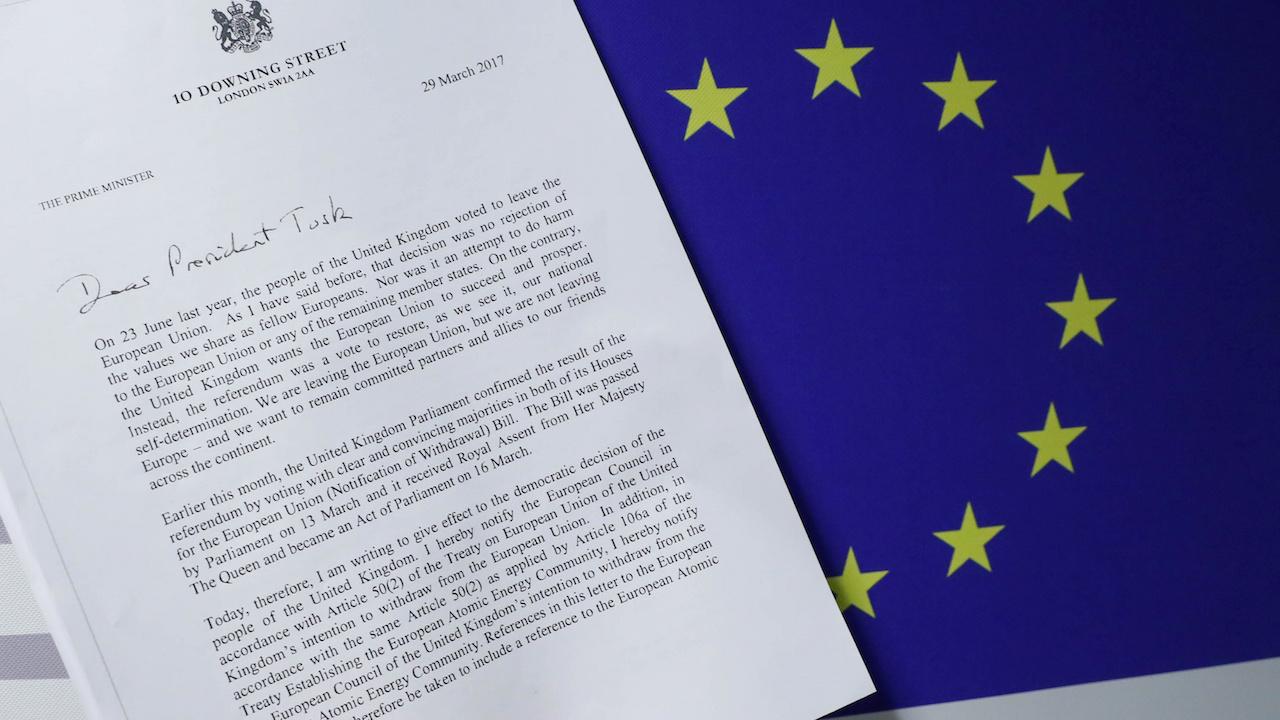

A copy of British Prime Minister Theresa May's Brexit letter stating the UK's intention to leave the EU, under Article 50 of the bloc's Lisbon Treaty, and the European flag.

Britain's relationship with the European Union was always an awkward marriage of convenience rather than a case of love at first sight.

And after 44 years — during which trade ties always took precedence for Britain over closer integration — London has filed for divorce.

Anand Menon, a professor of European politics at King's College London university, said the relationship was always "transactional" and therefore the break-up is "pretty logical."

"It's been a utilitarian relationship since 1973 and the emphasis was always on the economic dimension, not on the political one," said Pauline Schnapper, professor of contemporary British history at the Sorbonne University in Paris.

"The sentimental dimension is near non-existent," she said.

The path towards today's European Union began after World War II as the shattered continent tried to rebuild and deepen integration as a way of bolstering the peace.

The project did not immediately appeal to Britain.

"I think we didn't feel vulnerable enough to join, quite simply," Menon said.

Britain preferred to focus on its special relationship with the United States and the remains of its empire.

London nevertheless supported the push for closer integration on the European continent: wartime prime minister Winston Churchill called for the creation of a "United States of Europe" in a 1946 Zurich speech.

But in the early 1960s, Britain's fortunes changed for the worse.

Its economic growth started lagging behind that of France and Germany, making the European single market on its doorstep seem an appealing option.

Club of 'others'

Britain on Wednesday began what is expected to be two years of difficult divorce negotiations with a formal notification by letter to EU President Donald Tusk.

Joining the European fray in the first place was not an easy task.

In 1961, France's then-president Charles de Gaulle vetoed Britain's first application, seeing it as a "Trojan Horse" for the United States and doubting Britain's European spirit.

Another French veto followed in 1967 and the UK was only finally welcomed into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973.

Unfortunately for Britain, the first oil crisis struck that same year and so the much-hoped-for economic boost failed to materialise.

Nevertheless, 67 percent of the British people voted to remain in the EEC in a 1975 referendum.

"The fact that we joined late is one of the reasons there are suspicions because obviously there is a sense that we joined a club that others had set up to suit themselves," Menon said.

Britain and the EEC soon locked horns and London began opting out of the major attempts to step up European integration.

In 1979, London refused to participate in the European monetary system, defending its national and fiscal sovereignty.

Six years later, it refused to ratify the Schengen Agreement — abolishing internal border checks — and in 1993, it opted out of the European single currency.

Britain's anti-federalist approach was spelled out by prime minister Margaret Thatcher during a 1988 speech at the College of Europe in Bruges.

In it, she rejected the idea of a "European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels."

Conservative MP Bill Cash, a prominent eurosceptic, said earlier this month of the Brexit trigger: "This is an historic moment for which I and my colleagues have fought for 30 years. This is the moment."

"This is a vindication of the battles we fought," he said.

Not mutually beneficial

In the 1990s, Britain's defiance towards Brussels accelerated further with the creation of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which campaigned for the country's exit from the EU.

The opposition party's successes, particularly in the 2014 European Parliament elections when it topped the polls, pushed the government to harden its rhetoric.

The eurozone crisis, large-scale immigration from the EU and the refugee crisis of the past few years stoked the discontent, pushing prime minister David Cameron to call the June 2016 referendum.

Patricia Hogwood, a reader in European politics at the University of Westminster, said the referendum campaign failed to show the positive side of EU membership.

"This is an island mentality," she told AFP.

"We were always so scared of losing our control, losing our grip, our sovereignty," Hogwood added.

In the end, 52 percent of voters opted for Brexit.

Neither side is likely to end up the happier after the divorce, said John Springford, director of research at the Centre for European Reform in London.

"I am not convinced that Britain leaving the EU will help Britain or help the EU."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!