A Kremlin rival says he’s ready to be Russia’s president

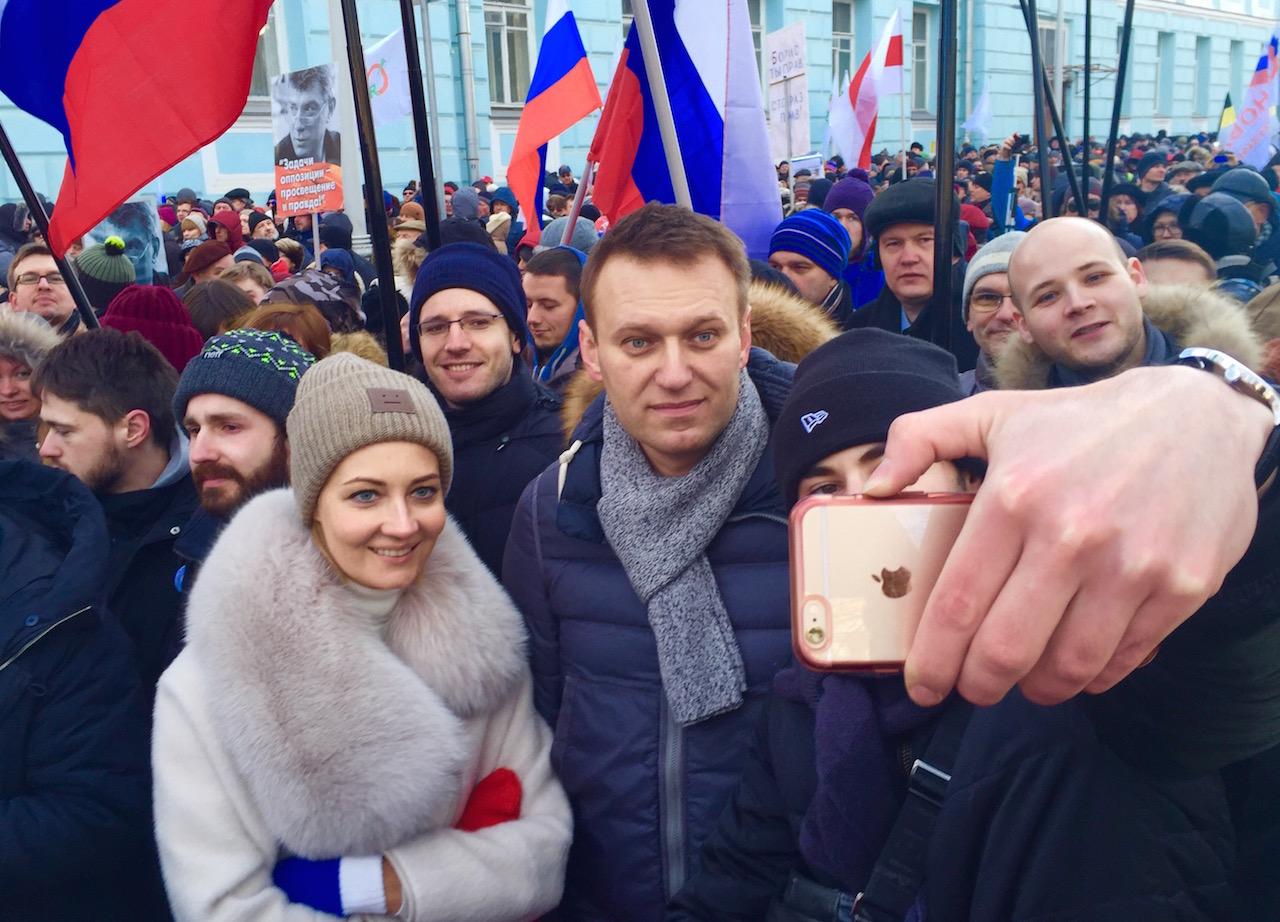

Alexey Navalny addresses a September 2015 rally on the outskirts of Moscow. The opposition has struggled to regain its footing following a wave of mass protests against the Kremlin in 2011.

With all the attention on Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential elections, one could be forgiven for failing to notice that the race for the Kremlin is already on.

President Vladimir Putin's current term ends in 2018. In a video message last December, Alexey Navalny, the anticorruption crusader and relentless Kremlin critic, announced himself as the first candidate to compete for the president's seat.

“There have been no true elections in Russia since 1996,” Navalny said, noting that most of those years were under Putin’s rule. “Without competitive elections, any government starts to degrade. And that’s what we see now.”

Several months later, the opposition leader is as committed as ever to running. And his vision for Russia clearly contrasts with Putin’s.

A Navalny presidency, he told The World in an interview, would mean “a normal democratic country” that uses its economic might — rather than its military — to be “a leader in Europe.”

"All that war rhetoric exists at the expense of the welfare of citizens of Russia," he says. "I think we can manage without that."

Protest days

Navalny’s own leadership skills were honed during Russia’s 2011 protest movement when tens of thousands took to the streets over allegations of rigged parliamentary elections.

A gifted public speaker and lawyer by training, Navalny delivered speeches skewering Putin’s ruling United Russia bloc as “the party of crooks and thieves.” The label quickly became the rallying cry of the street opposition.

But if Navalny’s raw political gifts were undeniable, so, too, was a flirtation with nationalist-tinged rhetoric that made some — urban liberals, in particular — uncomfortable.

But few of them would disagree that his Anti-Corruption Foundation, a crowdfunded NGO organized by Navalny in 2011, has been a thorn in the Kremlin’s side. The foundation routinely uncovers stories of graft and excess among President Putin’s inner circle.

An investigation published this month accused Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev of involvement in corrupt property acquisition schemes to the tune of $1 billion. The public seems to be paying attention: Anti-Corruption Foundation videos detailing their findings have racked up 13 million views and counting.

But Navalny has proven he’s also a campaigner. In a long-shot bid to be Moscow mayor in 2013, Navalny garnered 27 percent of the vote — short of victory, but nearly forcing a runoff against the Kremlin’s chosen candidate. Hundreds of young Russians volunteered in the effort despite state media that routinely painted Navalny as either dangerous or a US-backed stooge.

Vladimir Milov, an opposition politician who has publicly backed Navalny, called his re-entry into politics welcome news for opposition forces, particularly after opposition leader Boris Nemtsov's murder in 2015 and a disastrous showing by opposition parties in last fall’s parliamentary elections. The opposition failed to gain even a single seat.

“The one thing we need right now is to re-energize the community that is countering Putin at the upcoming elections and show the Russian people and the world that there is an alternative vision for Russia,” says Milov.

“And Navalny is the guy,” he adds.

Kremlin rules

But hovering over Navalny’s campaign is the question: Will the Kremlin even allow him to run?

In part, it’s a legal issue. Over the past few years, Navalny has faced a series of criminal charges — all fabricated, he insists, to stymie his political ambitions. Under Russian law, convicted felons can’t run for office.

It’s a drama still unfolding:

Last month, a Russian court found Navalny guilty of embezzlement in a retrial that independent observers say was politically motivated. (The judge’s ruling seemed identical to an earlier decision that the European Court of Human Rights found violated Navalny’s rights.)

The ruling seems to have ended Navalny’s campaign almost as soon as it began. But observers in Moscow argue that’s where Kremlin intrigue kicks in.

“They haven't yet made the final decision … that’s one thing I'm absolutely sure of,” says Russian political journalist Stanislav Kucher.

Putin is expected to stand for re-election next year for a fourth term. But Kucher says Putin craves a convincing victory — for which, the logic goes, he needs a genuine opponent. Enter Navalny.

“Look, you're saying in the West there is no opposition in Russia. Yes, there is,” says Kucher, explaining the argument. “You're saying there are no new leaders. Yes, there are. Look, here’s Navalny: strong, exuberant, charismatic … and he lost.”

Yet analyst Ekaterina Schulmann argues other Kremlin elites see inherent risks in allowing a Navalny candidacy to move forward, particularly after the election surprises of US President Donald Trump and the Brexit vote in the UK.

“I think if our political machine got some lesson from the American elections and the elections in Europe, [it] is that the people are extremely ready to vote for anyone and anybody so long as they vote against the establishment,” says Schulmann.

“This is dangerous,” she adds.

For his part, Navalny says the Kremlin worries that Russians tired of state corruption and a weak economy will flock to his message.

"The Kremlin perfectly well understands that we'll run a good campaign," he says. "Even if they have control of television, the election commission, the possibility to falsify the results or the possibility to use propaganda, they're still afraid of our campaign, which is built on volunteers."

Welcome to the paradox of Russia’s so-called "managed democracy," where just how serious a threat Navalny’s candidacy poses will likely determine whether the Kremlin lets him run at all.

Either way, Schulmann says Navalny’s candidacy injects drama into a race many had otherwise seen as a foregone conclusion.

“Now there are only two scenarios,” says Schulmann. “With Navalny or without him.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!