A sign at a February protest in New York calls for an end to immigration raids and deportations.

For some, the term "sanctuary city” is hardly new. It’s decades old, with roots in the 1980s — when churches defied federal officials and led efforts to house people escaping violence from Central America's civil wars.

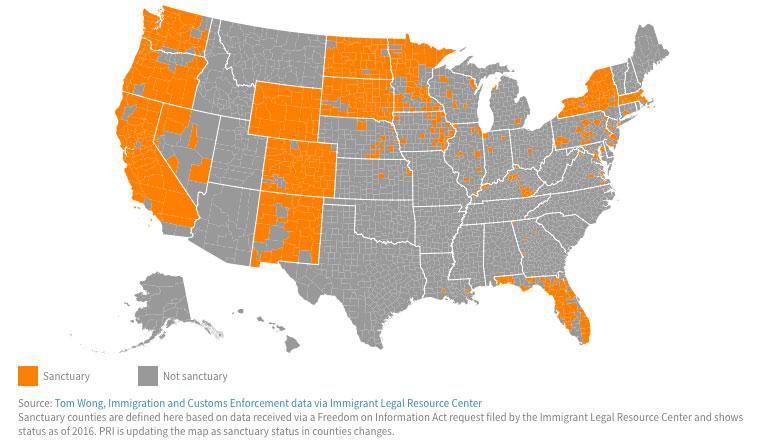

As the debate over immigration policies and their legality intensifies, the push to protect unauthorized immigrants from deportation has spread to more than 600 counties in 30 states. While policies vary, one tactic used by resistant localities is to limit cooperation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, when it comes to immigration detainers.

What are detainers? Simply put, they are ICE requests to local jails to hold arrested people in custody beyond their release date if they are undocumented. This gives ICE time to pick up and detain the person.

Those for sanctuary argue that police shouldn’t turn over to ICE immigrants who commit minor, non-violent crimes. It can lead to deportation regardless of their years in the US. Some police also say that complying with ICE detainers makes immigrants fear the police in general.

Those against sanctuary say such policies allow unauthorized immigrants, perhaps facing several criminal charges, to go free. They are public safety threats, critics say, although studies show crime is lower in sanctuary counties and that immigrants, with or without papers, commit less crime than US-born citizens.

Still, under President Donald Trump, the debate is becoming more polarized. He vows to crack down on sanctuary cities. Trump's executive order from January 25, parts of which have been put on hold by federal courts, states that “these jurisdictions have caused immeasurable harm to the American people” and directs the administration to strip them of federal funding. But it’s unclear to what extent the government can do that, and legal pushback is certain.

Beyond the Trump threats, there are other pressures on local communities to enact or eliminate sanctuary policies. As counties change their status, we'll update these maps accordingly.

All sanctuary counties

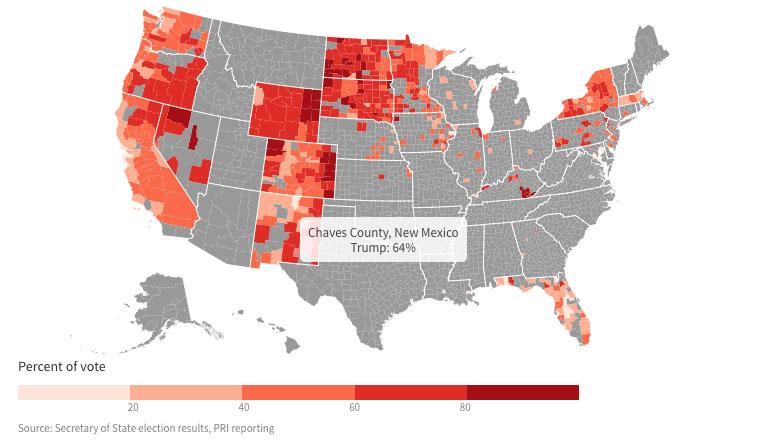

Support for Trump in sanctuary counties

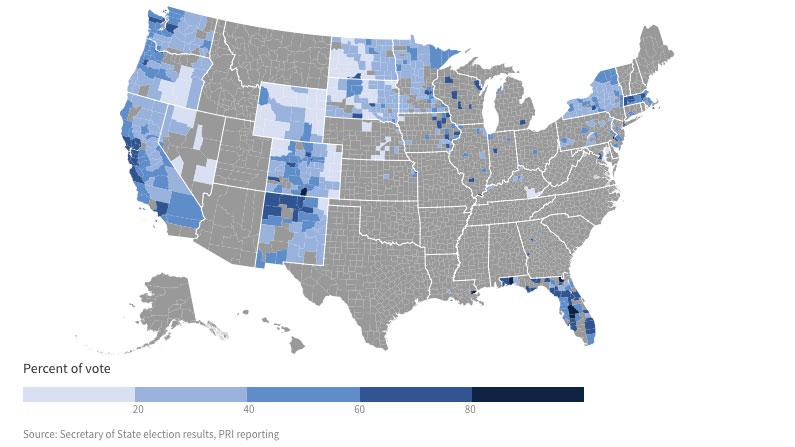

Support for Clinton in sanctuary counties

But just because a city calls itself a sanctuary doesn’t mean ICE can’t just show up and arrest people. We saw this happen under Obama — and we’re seeing it happen now.

Austin mayor Steve Adler says he didn’t get any notice when ICE launched an operation there, — arresting people who hadn’t even been charged with crimes.

“They were picking up people who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time — nearby somebody who was being targeted,” he says. “It looks as if over half of the people picked up in Austin were people that were not being targeted.”

Adler said some people called 911 recently when ICE agents showed up.

“I don’t see our officers stopping or hindering federal officials from doing their jobs,” Adler added. “That’s not their job.”

Of course, there are plenty of people who support stepped up deportations and oppose sanctuary policies.

Sabine Durden’s son, Dominic, died in Riverside, California, when his motorcycle crashed into a truck driven by an undocumented Guatemalan man, who didn’t have a driver’s license and had a record with two DUIs.

But he lived in a sanctuary area, so his record wasn’t enough to hand him to immigration.

Durden has met with Trump.

“He cried with us. That’s why I’m glad when President Trump talked about his new program. We don’t have anyone fighting for us,” she says.

There are sad stories on the other side, too. Alejandro, who asked not to be identified with his full name because he’s undocumented, lives in Alameda and has three children, all US citizens. A few years ago, he got a DUI, and because Alameda cooperates with immigration – he’s now fighting deportation.

“I’ve been in the United States half of my life, which is close to 14 years. I’ve been working really hard, really, really hard since the beginning, to have just a better living, not just for myself but for my kids,” he says.

And he is well aware that if he lived just across the Bay Bridge, in San Francisco, a sanctuary city, he may not be facing deportration. There, the local police may not have turned him over to ICE because of a DUI. “It’s like I’m literally four miles away from San Francisco,” he said.

Four miles away from a different cirumstance, one that would not put his years in the US in the balance.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!