Poland’s right-wing government thinks this WWII museum isn’t ‘glorious’ enough

The Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, Poland, is pictured here.

Pawl Machcewicz is a man on the wrong side of history.

He is the director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, Poland. After eight years and millions of dollars invested, Machcewicz rushed to open the museum last month before it was fully completed. Why? Because he feared that his museum, in its current form, was in danger of never being allowed to open.

The Polish government threatened to fire Machcewicz and merge this new, multimillion-dollar investment with another, yet-to-be-built museum. And it seems the government will get its way. On Wednesday, Poland's Supreme Administrative Court ruled in favor of a government-proposed merger with a newly comissioned, yet-to-be built museum in Gdansk.

"Two museums focused on similar themes operating in the same city would not be justified from an economic and organisational standpoint," Poland’s culture ministry said in a statement Wednesday, "The merger of both institutions will go ahead immediately."

Officially, the Polish Ministry of Culture states that it's unhappy with the museum because it has gone over budget and has taken too long to build. But underneath this statement is an ongoing debate in Poland about history. The minister of culture has made public statements criticizing the way history is being presented at Machcewicz's museum — that it doesn’t conform to official “historical policy.”

“What I love about the Polish phrase is, you can translate it, 'historical policy' or the 'politics of history,' either way,” said Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, chief curator at the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, and one of the historians who attended a rushed opening of the museum back in January. The way she described it is that the museum isn’t Polish enough for the government.

“I honestly can’t fathom their reasons,” said writer Konstanty Gebert. “A government that wants to rule history is insane unless of course, we’re in '1984.' We’re not.”

Poland is far from George Orwell’s totalitarian regime Oceania. However, the country is riding the wave of nationalism. After eight years of a liberal government, in 2015 the right-wing Law and Justice party was narrowly voted in on a campaign promise of making Poland great again. Their campaign slogan: “Poland off your knees.” As in, Poland will no longer kneel before Europe nor Russia.

This idea of a strong Poland is key. One of the government's main obsessions is controlling this narrative that Poland has been strong throughout history.

Eight years ago, Machcewicz wrote an editorial for a Polish newspaper declaring it high time for the country to build the comprehensive museum of World War II. To his surprise, the previous government gave him the green light. But from the start, the Law and Justice party publicly challenged his idea.

“They criticized that this museum does not represent the glorious side of the war, they criticized that this is a pacifist museum, that we show the war as a great tragedy,” says Machcewicz.

The war according to the Law and Justice party can “shape characters and make people brave and industrious.”

“It’s a little bit outrageous and offending to me because I’m a Polish historian, and I’ve devoted most of my life to Polish history and I don’t need any politician to teach me,” said Machcewicz. "But in a way, I expected it’d be coming."

It’s hard to understand why history matters so much in Poland without understanding the effect World War II had on this nation. Americans looking back on the war tend to think of the Greatest Generation, beating down fascism and Tom Hanks heroics.

But it was a very different war for Poland.

The first shots of the conflict were fired here, where the museum was built, in Gdansk. And for six years, Poland was fought over on both fronts, occupied by Joseph Stalin and the Soviets in the east and the Germans in the west. It was a bitter battle on Polish soil. No village was untouched.

More than 5 million Poles died during the war, 3 million of them Polish Jews — one-fifth of the population.

Many Polish families still live in the war's shadow.

“I remember the stories of my mother,” said Machcewicz.

Machcewicz’s mother was 4 years old during the Warsaw uprising. She remembers the day when German soldiers came to her house, took her family to a square and began executing people.

“So, my mother saw people who were killed, blood, people falling down.”

These are his mother's first memories. Many Polish families have similar stories. In fact, after the museum put out a call to Poles to donate their personal relics from the war, Machcewicz and his staff were inundated with objects.

“Just in a few months, we got three- or four-thousand objects,” he said.

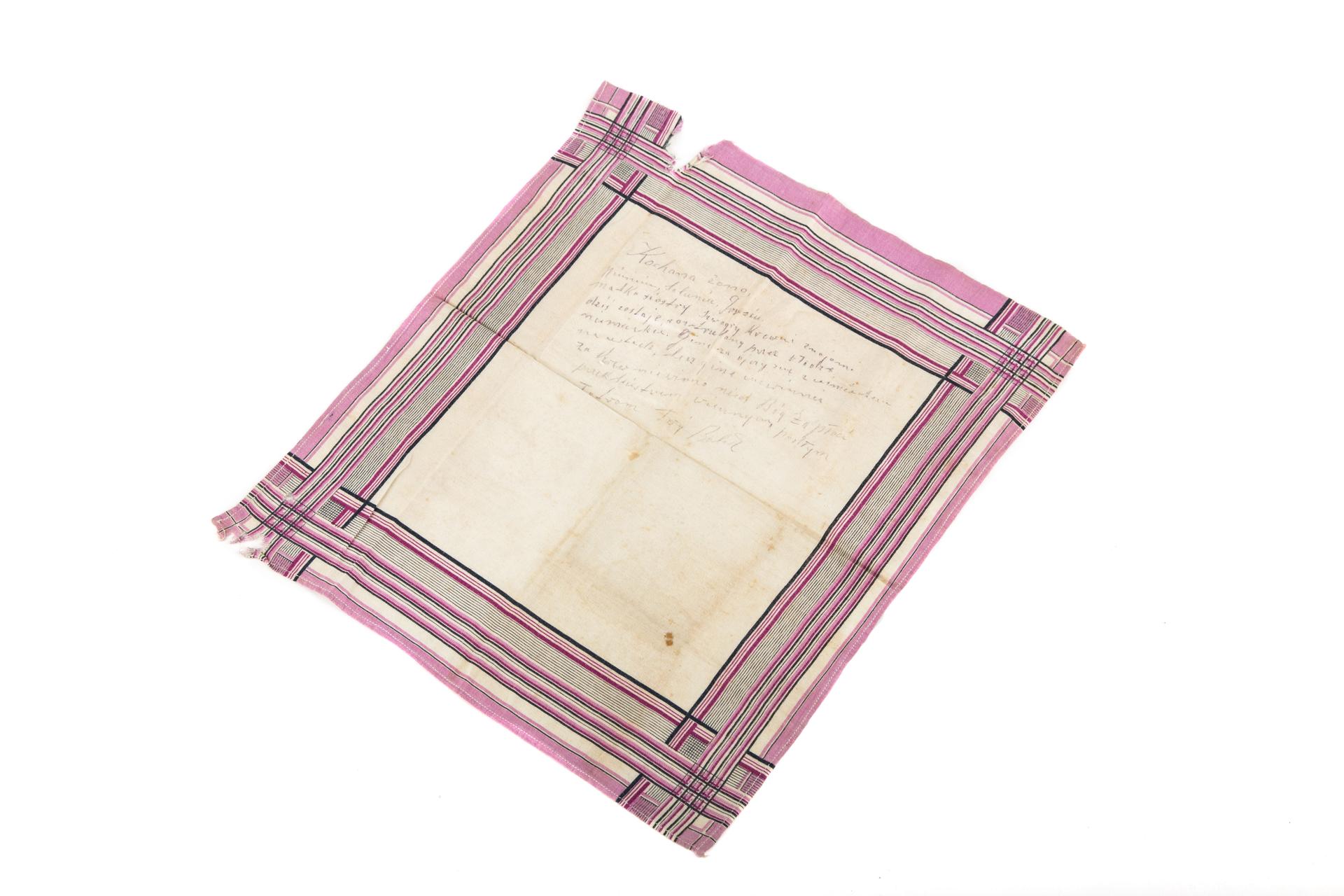

One of those objects is a wartime letter donated by Joana Penson. Penson, now 95, was just 17 when the war began. She was part of the Polish resistance. She was caught by the Germans and sent to the Ravensbruck concentration camp in Germany for four years.

“For me, it is not exhibition, it’s rather my memories. It’s evoking my memories,” said Penson.

Machcewicz told reporters on Wednesday that this merger was nothing more than an attempt by the government to get rid of him. "In my opinion, this was the main reason for merging the museums," he said.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!