Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe relaxes for a moment on a bench in front of St. Monica's Girls' Vocational School in Gulu, Uganda.

When Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe was first assigned to be director of Saint Monica’s Girls' Vocational School in 2002, a Catholic mission in the northern Ugandan city of Gulu, she was a little worried. She was supposed to teach tailoring to 300 girls and, frankly, she didn’t know the first thing about sewing. When she got there, she found that sewing was the least of her concerns.

At that time, northern Uganda was in the midst of a civil war. A Christian militia known as the Lord’s Resistance Army had been trying to take over the north for about 15 years. The LRA abducted children, usually at night. They stole about 30,000 children over the course of the war. The boys were forced to be child soldiers; the girls were trafficked and forced to marry soldiers.

Children became terrified of sleeping at home. Every evening, to avoid being snatched, a procession of boys and girls would pour into the dirt roads and walk to the city. They were known as night commuters. And a lot of them came to Saint Monica’s.

“Almost every day, we were housing from 300 to 500 children,” Sister Rosemary explains.

Sister Rosemary took in every child who showed up — even though she didn’t have space. She placed them in spare rooms, storage units, hallways. She asked boarding schools for the broken bed frames they discarded, and she had them welded back together. She asked other religious orders for money, to give these children at least one meal every day.

But soon, she found out that these children needed more than food — especially the girls. When girls who'd escaped the LRA arrived at her school, many came with children born of rape — children they had trouble connecting with.

“I personally realized it was not easy for these girls to be encouraged to love children who reminded them of their pain — children from their captors.”

Sister Rosemary explains that Uganda is a deeply tribal society. Communities will reject a mother and her child born of an unknown man.

When the boys escaped from being child soldiers, they could come back and get an education. But girls had to subsist as they could and take care of their babies. Going to school was not an option.

“They are not free,” says Sister Rosemary. “Why are they not free? They don’t have education. They were taken at early childhood education.”

So, Sister Rosemary decided to dedicate her life to these women and their children. She started a day care. And then, she started a literacy program.

Sister Rosemary walks through the compound. “This is where they used to sleep,” she explains.

It’s practically empty. The Ugandan conflict ended around 2006. No more night commuters. No more children scrambling into padlocked storage rooms, hoping to sleep safely. Now, those kids are grown-ups. And it’s harder to drum up empathy for adults. A lot of foreign aid evaporated. Ironically, Sister Rosemary says, this is exactly the time when it’s needed most.

“This is the moment we are supposed to start rebuilding lives,” she says.

In 2013, when civil war broke out across the border in South Sudan, she was ready. Over a million refugees from South Sudan have come across the border. And there are widespread reports of assault against women by South Sudanese soldiers.

Sister Rosemary has opened a second vocational school in Atiak, Uganda, on the border of South Sudan.

“I think in any situation, or conflict, women are more disadvantaged. And to tell you the truth, many of them choose not to even talk about it.”

Now, her schools in Gulu and Atiak teach skills to girls who’ve been victims of war — no matter where they're from.

Around the time when South Sudan unraveled into violence, Sister Rosemary came up with a plan to raise money to help the girls.

Someone had gifted her an unusual purse. And she did something pretty rude for such a sweet little lady.

“I ripped it in pieces, and then I decided to put it back together.”

She ripped it, reassembled it and repeated until she’d figured out how to make a similar purse.

In an airy room in the compound, we find a couple of girls stitching and working on sewing machines.

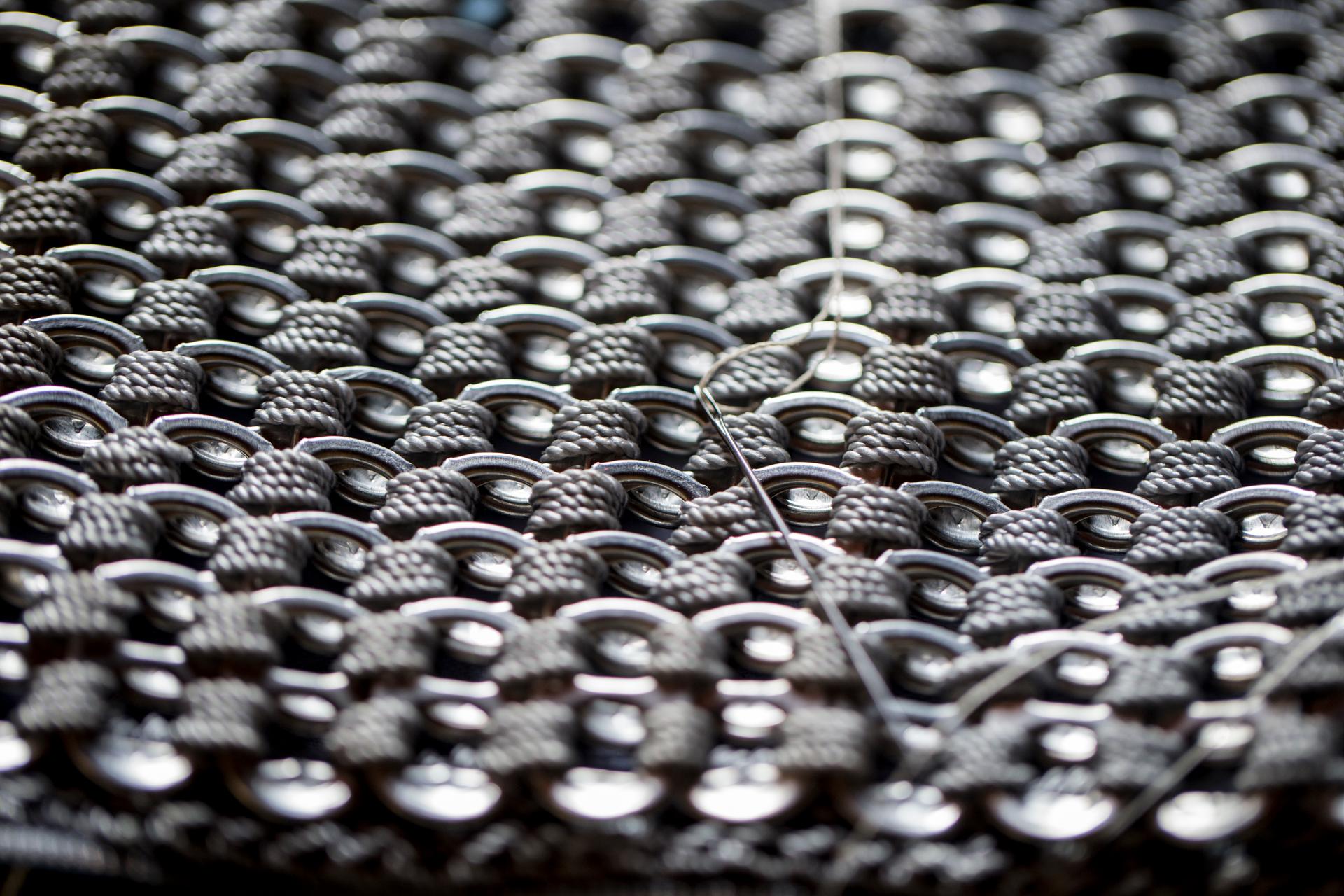

“How many purses can you line for me today? I need 20!” she exclaims to the young woman at the sewing table. The program is called Sewing Hope. It teaches girls and women to make purses out of discarded soda can tabs.

The final result is quite stunning. It looks like liquid aluminum, like metallic mesh, or chain mail.

Sister Rosemary might have never heard of The Clash, but the bags have a very punk rock feel to them.

And she says, beyond the final results, the way they are made is therapeutic.

“You take something nobody one wants anymore, and you patiently build something beautiful. Stitching, one stitch at a time. It’s like stitching your life one stitch at a time,” she says.

For 15 years, Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe has been picking up the broken pieces and putting them back together.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?