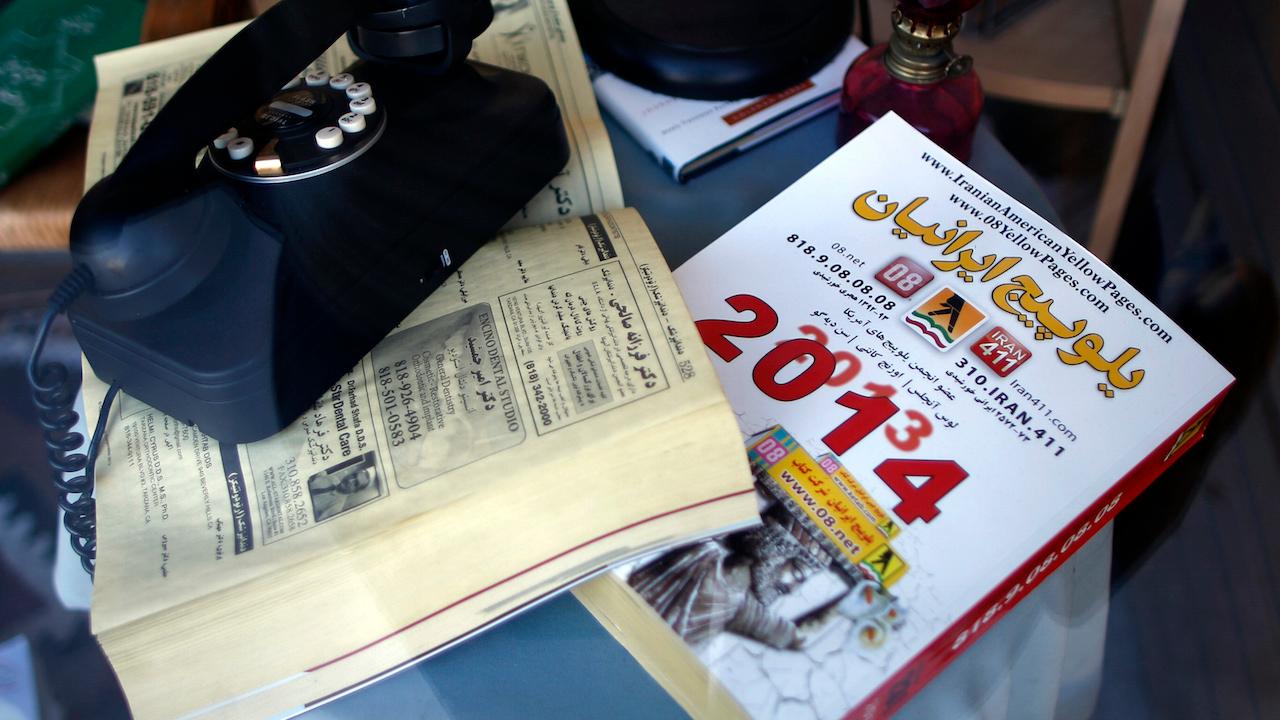

An Iranian American phone book sits in a store window in the Westwood district of Los Angeles, California, near "Persian Square," on Aug. 12, 2014. The area is home to many migrants from Iran. Persians are one group, however, who may be undercounted by the US census.

I’m half-Palestinian, half-English. I have often been mistaken for a range of ethnicities along the brown spectrum, from Italian to Indian. When people hear my name they often mistake me for a Muslim. What they never mistake me for, however, is white.

And yet, in America, that's how I'm classified. For the time being, anyway.

The US census defines “white” as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.” So a dark-skinned Christian Egyptian, a light-skinned Sunni Syrian, a Shiite Iranian — they’re all eligible to tick the "white"’ box. They don’t have to, of course. They can select "other." What they can’t tick is a box that reflects Arab or Persian identity.

This is likely to change soon. The Census Bureau has recommended that a new Middle East and North Africa (MENA) racial category be added to the next census, coming in 2020.

This could be interpreted as an alarming development: Americans descended from the MENA region are going to stop being counted as white, at the same moment President Donald Trump is fighting hard for a ban on travelers from several Muslim-majority countries. However, many Arab Americans view the new category as a positive step. Advocacy groups, in fact, have been pushing for this change for a while.

Once upon a time there was a clear advantage to being classed as white on the census, even if you didn’t actually identify as such, and weren’t treated as such by most people. The advantage was citizenship: Until 1952 you could only become a naturalized American citizen if you were white. This spurred a number of court cases at the beginning of the 20th century, as various immigrants from the MENA region argued that they were white and thus eligible for citizenship, rather than of “Chinese-Mongolian” ancestry, a suggested classification.

In 1909 a Californian court ruled that George Shishim, a Syrian-Lebanese immigrant to Los Angeles, was white. That case became precedent for other states. (Oddly enough, Shishim won the case by invoking Jesus. “If I am a Mongolian, then so was Jesus, because we came from the same land,” he argued.)

Following the elimination of race as a basis for naturalization, there was no longer the same advantage to being classified as white. Indeed, it became a distinct disadvantage. You don’t count unless you’re counted — and Arabs and Persians were effectively whitewashed in official documents, while they faced discrimination in the real world.

Not being counted officially has significant real-world consequences. While the Census Bureau estimates there are around 1.8 million Arab Americans in the United States, the Arab American Institute (AAI) puts that figure closer to 3.7 million. As the AAI explains, the undercounting of Arab Americans “has served as a barrier to representation, education, health, and employment for the community” in numerous ways. It effects, for example, the availability of foreign language ballots at polling places; research grants for ethnic-specific diseases; and protection against discrimination.

The new ethnic category isn’t the only notable change being made to the 2020 census, which will also see the removal of the word “Negro.” While it may seem like an outdated and offensive term, Census officials defended its inclusion in the 2010 Census by arguing that “statistics from the 2000 Census [show] there are still some segments of the population who identified with the term.”

The census is a fascinating reflection of shifting demographics, social mores and attitudes to race in America. The first census in 1790 had just three categories: “free whites,” “other free persons”, and “slaves.” In the centuries since, the categories have proliferated and morphed. As Pew Social Trends notes, “The category names often changed in a reflection of current politics, science and public attitudes." For a while the census also included the categories “quadroon” and “octoroon” for people who were one-quarter or one-eighth black.

The ever-shifting Census is a reminder of just how much time white America has spent agonizing over definitions of “the other.” White Americans, meanwhile, have always been able to take their identity — and its official representation — for granted in a way that other groups haven’t.

However, as demographics shift, all this is changing. The number of mixed-race births is growing, and the Census bureau projects that non-Hispanic whites will be a minority by 2044.

Arwa Mahdawi is a writer and brand strategist based in New York.