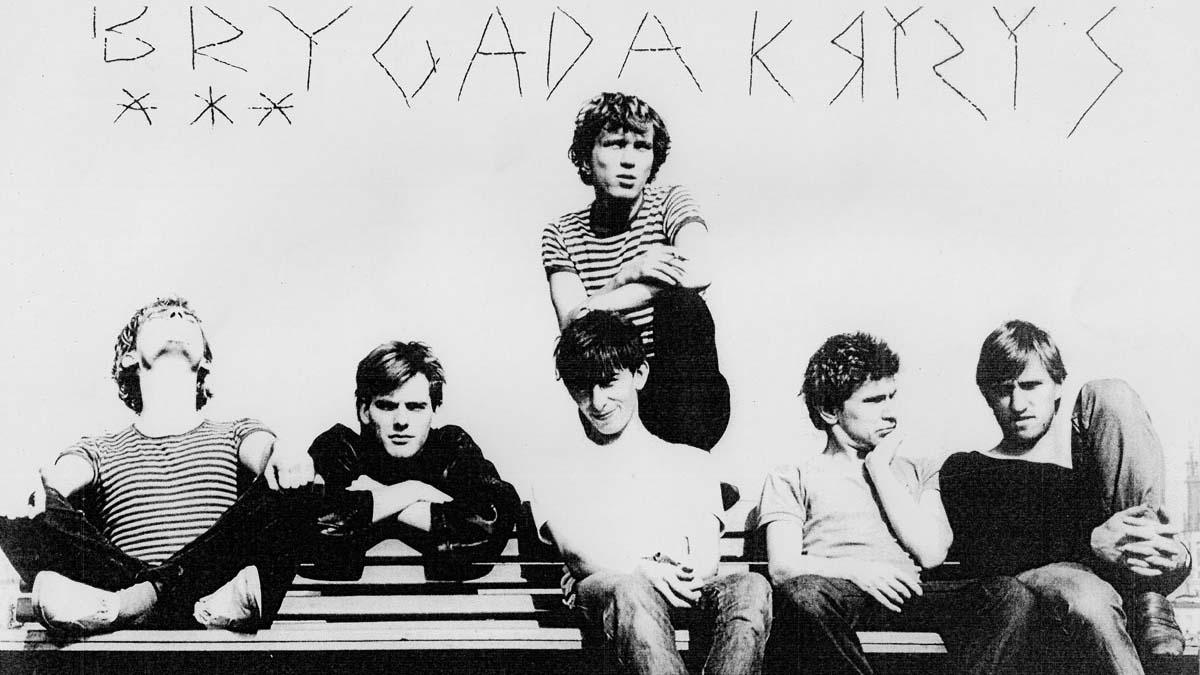

Tomek Lipinski and friends formed the band Brygada Kryzys in 1981 just before martial law was declared in Poland.

Punk came into Tomek Lipinski’s life in the form of a cassette tape. The year was 1978 in communist Poland.

“The Polish press used to write about wild British teenagers who couldn’t play at all, who made their own instruments. We were curious what it was about,” remembers Lipinski. “The first thing I ever heard was the taped copy of the double album from Roxy Club.”

“The Roxy London WC2” album was recorded in London’s Roxy Club in 1977, featuring bands like X-Ray Spex and the Buzzcocks.

“It was mind-blowing,” Lipinski says.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DYdwGW02TxMk

It’s not hard to imagine Lipinski, with his graying ponytail, as a wild Polish teenager.

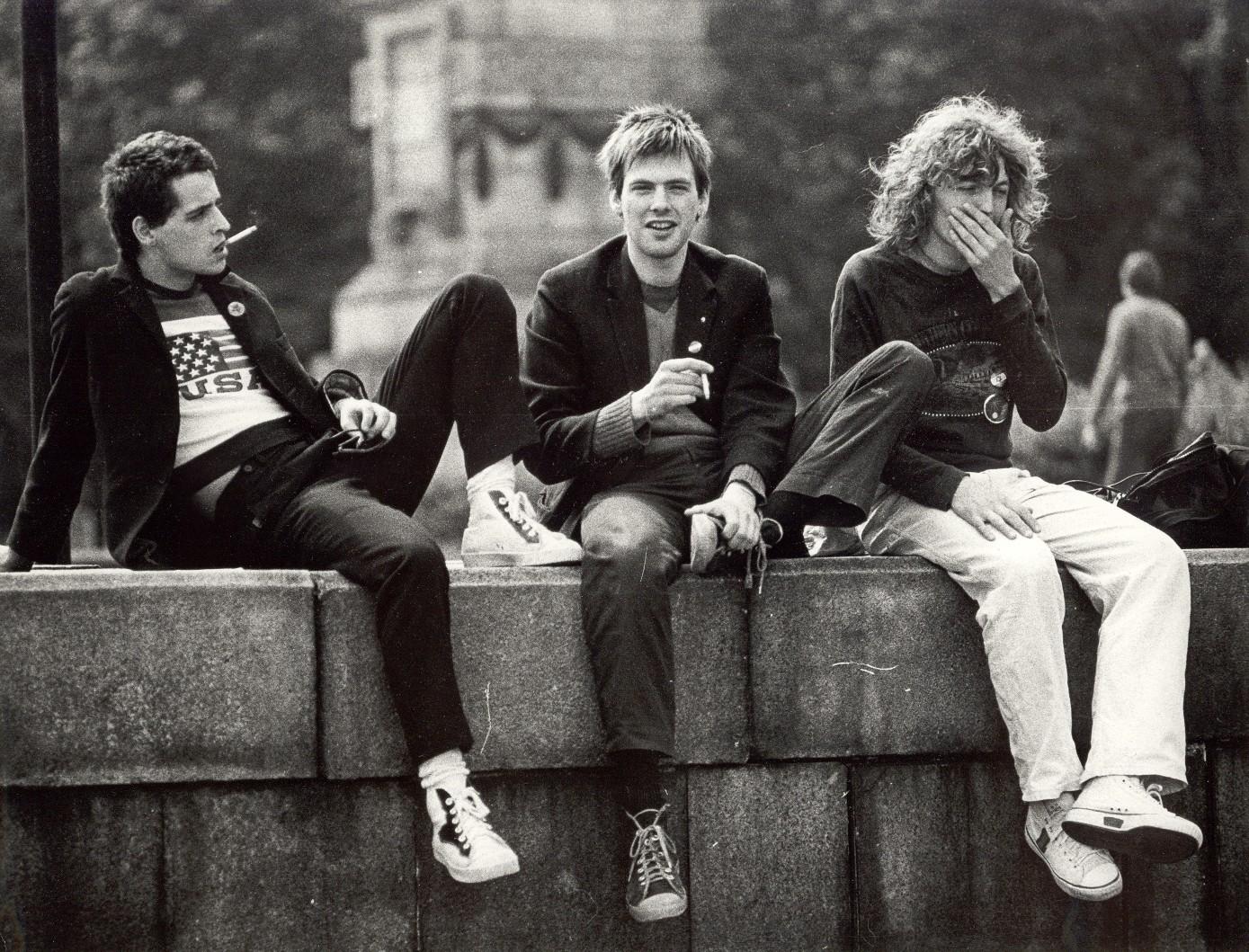

But being a punk behind the Iron Curtain took commitment; Western music wasn’t easy to come by. There weren’t music stores with the latest Buzzcocks album.

Everything was traded person-to-person, on cassette tapes.

“Usually it was some private connections, family connections. My first four punk albums came from London, from my sister,” Lipinski says.

And then he would record those albums onto tapes and trade them for different albums. Cassettes were precious commodities, he says. “Taped and taped again, copies from copies, copies from copies and so on."

Since childhood, Lipinski was a fan of music, but when he heard that Roxy Club album for the first time, he felt the desire to make music himself.

“OK, if they can play simple music, which is so packed with energy, and the energy and the message is much more important than your skills, I said, ‘OK, I can play,’” he explains.

When the British band The Raincoats came to Warsaw in 1978, he decided to form a band.

“They were here and they brought this feel, this vibration, this energy in real people," Lipinski remembers. "We could talk to them; we could ask questions."

One of them wrote him lyrics to a song. Lipinski recalls them with a huge grin.

I got caught in the Palace of Science

I got followed in the library

It don’t matter ‘bout the bugs in my mattress

Rocket in my pocket but no flies on me

Joseph put the style in me

Joseph put the style in me

Joseph put the style in me

If you come in it’s a party

And you got to be free

There’s no discussion at all in the Forum

There’s no one watching in the gallery

There’s nothing better than to go to the Party

Everybody knows that that’s Democracy

Joseph put the style in me

Joseph put the style in me

Joseph put the style in me

If you come in it’s a party

And you got to be free

The next summer, Lipinski started his first band, Tilt.

Then in 1981 he formed Brygada Kryzys, which quickly gained a following. Their songs were in English. They were cheeky, middle-finger-to-the-man kinds of songs, like “F.U.C.K.”

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D3F4yTmk8-2k

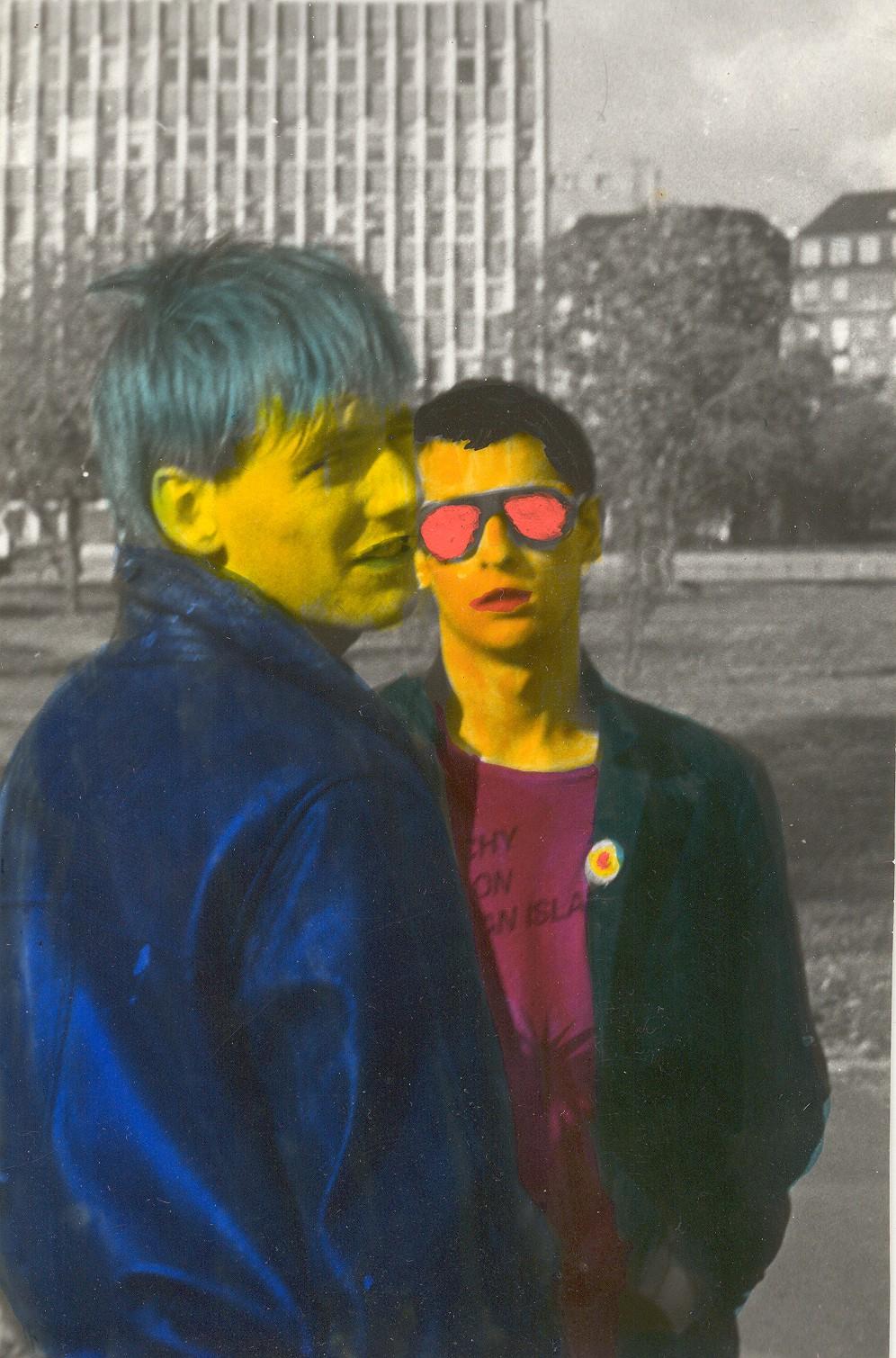

Lipinski wrote and sang in English because it was the punk thing to do.

“At that time artists who performed in English couldn’t be aired in Poland, so you had to sing in Polish and you had to be Polish,” he says. Well, punk is all about breaking the rules. “You can’t sing in English? We will sing in English.”

This didn’t go over well with Polish censors. They asked Lipinski to translate all of his English lyrics into Polish.

So he says he wrote different, nonsensical lyrics that somehow passed muster with the censors.

“It sounded like Dadaist poetry because it didn’t make sense,” he says.

The government didn’t like the band’s name either. Brygada Kryzys translates to Crisis Brigade. And Poland in 1981 was incrisis. The government had just declared martial law. In February, the government organized a rock concert to distract from the tensions.

Brygada Kryzys was supposed to play at the concert.

“They put us on posters as 'Brygada K.' and we opposed. We said either you put our full name or we’re not playing,” says Lipinski.

“They were afraid of the word 'crisis,'” he adds. “They introduced martial law and the crisis was 'over.'”

Martial law continued in Poland for more than two and half years.

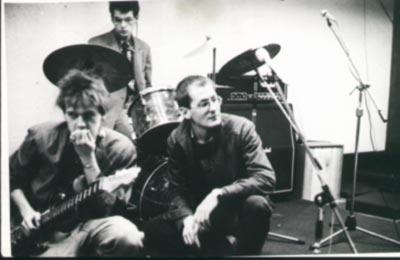

“Paradoxically it was the period when rock music boomed in Poland,” Lipinski says.

But state-sponsored rock concerts in communist Poland were far from any punk show you might envision. No crowd surfing or mosh pits.

Lipinski remembers being on tour in 1981:

“I remember one gig [in Lodz], not far from Warsaw. [There was an] enormous crowd of people there and of course they wanted to stand up and dance but they couldn’t. Whoever started to dance was taken out. And I’m standing on stage watching, and it was something really ugly. I could go on and on with stories like that."

Still, he says, however strained these concerts might’ve been, however censored the music, music was the only escape. His only escape.

“As a young man, in this far away country in Eastern Europe music was for me was the most important thing in my life. [Music] was the wide world coming to this dark place.”

Brygada Kryzys hasn’t recorded an album since the mid-2000s, but Lipinski still plays music for a living. It’s a bit softer now.

“I think I’m getting old. It’s a symptom,” he laughs.