How might a Justice Gorsuch rule on environmental cases before the Supreme Court?

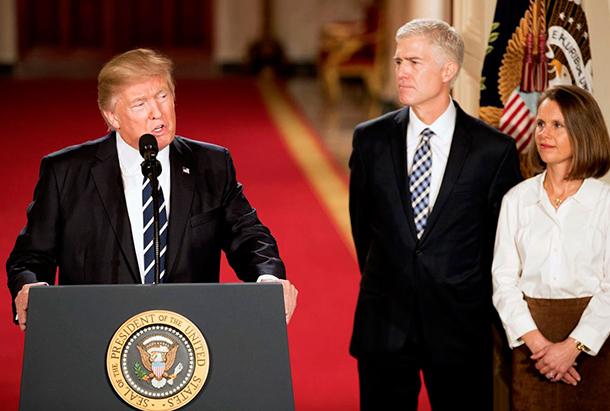

President Trump announces his nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to the US Supreme Court as the judge and his wife, Louise, look on.

President Donald Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the US Supreme Court has sparked widespread speculation about how the appellate judge might rule on upcoming cases in the court’s docket, including high-stakes cases on environmental issues.

Gorsuch's narrow interpretations of agency powers, as well as his lifelong experience as an outdoorsman, could inform his findings if he is confirmed, but “it’s hard to read him because he has not written that many major environmental cases,” says Vermont Law School Professor Patrick Parenteau.

“He is most known for his opposition to what we call the Chevron doctrine, the doctrine that defers to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes,” Parenteau explains. “This is the issue at the forefront in the Clean Power Plan [an Obama policy aimed at curbing climate change] litigation. It's probably fair to say that Judge Gorsuch would be very skeptical, like Justice Scalia, of EPA's assertion of broad authority under a narrow provision of the Clean Air Act. So, in cases where there's a rule with major economic consequences, Judge Gorsuch is certainly going to lean towards the business side of the argument.”

“The irony, of course, is that if anybody needs the Chevron doctrine to do what he wants to do, it’s Trump's choice to head the EPA, Scott Pruitt,” Parenteau continues. “If Mr. Pruitt wants to repeal Obama's environmental rules, he's going to need the Chevron doctrine to do that, and Judge Gorsuch sounds like he's not inclined to give a lot of weight to the agency's reinterpretation of statutory language. So, this doctrine cuts both ways; it may actually end up impeding the Trump administration's attempts to roll back environmental rules.”

Critics of Gorsuch have called him a friend of fossil fuel companies and big business, but while one “can discern a business-friendly approach to questions where environmental regulations impact industry, he is also known as quite an outdoorsman,” Parenteau says. “He comes from Colorado. He's a fly fisherman. He's a skier … so, he's a mixed bag, I think.”

As an example of how Gorsuch might interpret laws and regulations, Parenteau points to a case in which Gorsuch upheld Colorado's renewable portfolio standards. The challenge came from an industry group that claimed the standards were unconstitutional, under the "Dormant Commerce Clause."

“The case involves some interesting facts, so you can't extrapolate too much from his decision upholding the Colorado law,” Parenteau says. “But the one thing that's clear from his description of this Dormant Commerce Clause doctrine is that he thinks it can go too far in striking down state laws, regardless of whether they're for renewable energy or anything else. So, he tends to side with the states, which is consistent with his conservative philosophy.”

In a somewhat odd plot twist, especially to environmentalists, Judge Gorsuch is the son of Anne Gorsuch Burford, President Reagan’s first EPA administrator. Anne Gorsuch moved to slash the EPA’s budget by almost half and then she was forced to resign less than two years into her term after some conflict-of-interest questions arose involving a toxic waste matter.

“Neil Gorsuch doesn't get to pick his mother, so we can't blame him for that,” Parenteau says. “I suspect in his upbringing, he probably heard a lot of conservative rhetoric in the household around the dinner table, and he seems to reflect a lot of that. But, I actually take some solace in the fact that he's an avid fly fisherman, which means he spends a lot of time outdoors. He understands the habitats that are necessary to produce high-quality trout habitat, so that's a good sign. That he's connected in some way with the natural world probably means he's more open to arguments when rules are designed to protect those kinds of resources that he himself loves. That should be a good thing.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?