Trump removes ‘climate change’ from the White House website. History tells us regulatory change will take longer.

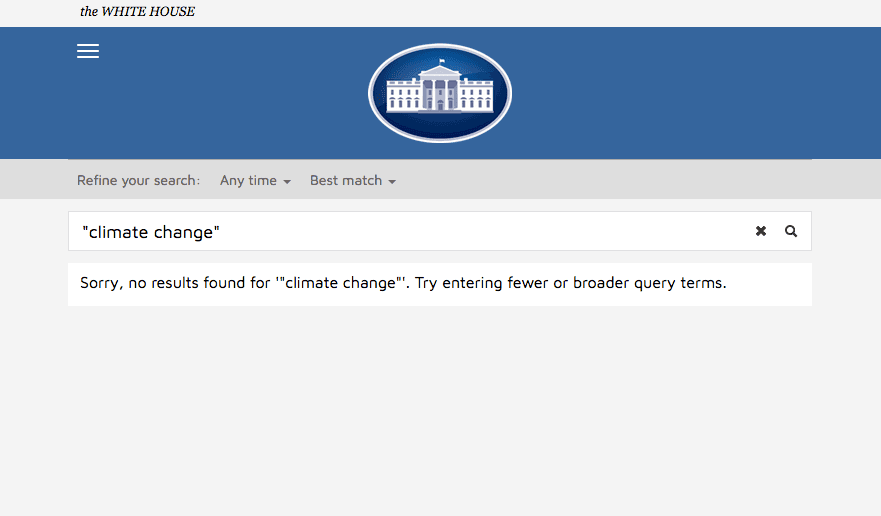

A screenshot of the WhiteHouse.gov website from January 20, 2017.

Shortly after Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th president of the United States, all mentions of the phrase “climate change” disappeared from the official White House website, whitehouse.gov.

The site now outlines Trump’s “America First Energy Plan,” which promises to roll back clean water rules and efforts to fight climate change.

The plan echoes pledges Trump made during his campaign and after his election.

In the proposal, Trump commits to eliminating the Climate Action Plan, a sweeping set of policies aimed at cutting carbon pollution, inlcuding a number of President Barack Obama's executive actions. Trump also promises to eliminate the Waters of the United States rule, a technical document that defines which waterways come under the jurisdiction of federal regulators under the Clean Water Act. The 2015 rule is intended to protect smaller streams, tributaries and wetlands from development and has drawn sharp criticism from Republican lawmakers and from farm and manufacturing interests.

During his campaign, Trump also promised to lift moratoriums on coal leasing on federal lands and said he would “cancel” the 2015 UN climate change agreement.

Other rules thought to be at risk at the beginning of Trump’s tenure include the Bureau of Land Management Methane Rule and the Streams Protection Act. Those recent acts could be quickly overturned using the Congressional Review Act, which allows lawmakers to rescind a regulation within 60 legislative days of publication.

Many other rules, however, could take years to reverse.

“The announcements may come fast and furious, but actually rolling back regulations takes some time,” says Jody Freeman, head of the environmental law program at Harvard Law School and a former Obama energy and climate change advisor.

For example, Trump could announce that he would withdraw the US from the Paris agreement on Day One, but executing that withdrawal requires a legal process that takes four years.

Likewise, rescinding the Clean Power Plan that limits CO2 emissions could also require a lengthy legal process. (The legality of the rule is currently being challenged in court.)

History as a guide

If history is a guide, sweeping environmental reforms could be blocked if they overreach the public’s appetite for deregulation.

President Ronald Reagan campaigned on a famously anti-regulatory platform. Once he took office he sought to severely cut the Environmental Protection Agency’s budget. He appointed Anne Gorsuch as the agency’s administrator. Gorsuch was opposed to the agency’s mission from the beginning, Freeman says, and hired like-minded staffers.

Gorsuch eventually was held in contempt of Congress.

“[Gorsuch] wound up creating such a backlash that Reagan was forced to ask her to resign,” Freeman says. “So I think this is some indication of how an administration can really go too far and overreach, and if they do, that there can be a real public outcry.”

One check on Reagan's power was a Democratic Congress, which held hearings to publicize the administration’s rollback of environmental protections.

“I think the brakes in the system aren’t quite there this time, and so I think people are a little more concerned as a result,” Freeman says.

George W. Bush also came into office on a somewhat anti-regulatory platform, and attempted to block an arsenic standard for drinking water that had been approved in the final days of the Clinton administration.

“That resulted in such an outcry that in the end, they wound up adopting the very same standard that Clinton had put in place,” Freeman says.

Many Republican presidents have been good for the environment. Richard Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency. George H.W. Bush, Freeman says “wound up being one of our greatest environmental presidents.” He pushed for a stronger Clean Air Act to control acid rain and negotiated a key UN framework for international action on climate change.

“We have seen Republicans take the lead on environmental protection. I just don’t think that’s what we’re about to see from the Trump administration,” Freeman says.

The environment did not feature heavily in the campaign, and Trump is not viewed as having a mandate from voters to dramatically cut back on environmental protections.

A small online poll conducted in December showed that a majority of Trump voters support drinking water and air pollution regulations, as well as current climate change policies.

“I think he could be checked by public reaction, and I think that if he goes too far, he could well run into a public backlash,” Freeman says.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?