After Trump’s victory, a city debates offering ‘sanctuary’ to undocumented immigrants

US President-elect Donald Trump delivered brief remarks to reporters at the Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida, on Dec. 28, 2016.

"So, how do we go about this? Do we create a timeline?”

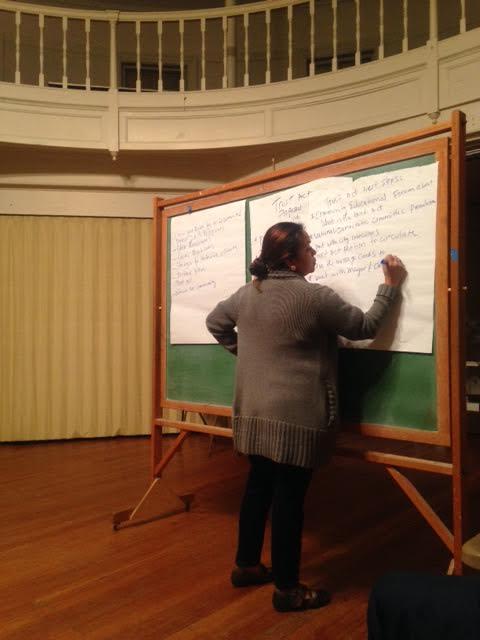

Isabel Lopez, an immigrant rights activist, stands in front of a chalkboard at a meeting in the back of a church in Brockton, Massachusetts, a town just an hour’s drive south of Boston.

Lopez, the leader of a group called the Brockton Interfaith Community, has been fighting for months to get a city ordinance passed that would make life easier for undocumented immigrants.

This ordinance — called the Trust Act — states that local police will not detain undocumented immigrants on behalf of immigration authorities — unless a criminal warrant has been issued.

This will not be an easy ordinance to get passed.

It was on the docket in Brockton in October.

But then, on the campaign trail, Donald Trump said he would cut off funding to “sanctuary cities” — cities where local officials have vowed not to help enforce federal immigration law.

Many feared that if the Trust Act passed, Brockton would be considered such a place. In response, city councilors in Brockton decided to wait until after the presidential election.

But then Trump won. And the Trust Act is on the docket yet again. For January.

This time around, though, the debate around it is even more complicated, even more contentious, even more emotional than before.

Only a few people attend Lopez’s meeting. They sit in a semi-circle on foldout chairs.

Usually, Lopez speaks quietly. But tonight she is loud.

“The reason you don't see people from the immigrant community right now, guess why?” she asks.

“They are scared,” somebody whispers.

“Right!” says Lopez. “They are scared. They are hiding. They are not going to work. They are not taking public transportation. They are not going to parks.”

Lopez’s point is that nobody should interpret a half-empty room as a sign that passing the Trust Act is no longer important for the immigrant community. If anything, it’s a sign that passing the measure is more important than ever.

Many undocumented immigrants, Lopez says, have been too afraid to leave their homes since the election, worried what the Trump presidency might mean for them.

The proposed Trust Act would make these immigrants feel safer, at least in Brockton, advocates say.

And this small group of people, huddled together in the back of a church, seem determined to make sure that it passes.

There are so many ideas on the chalkboard they hardly all fit.

For longtime Brockton Police officer Bill Healy, though, the issue is complicated.

He worries that if the Trust Act passes, the police department will lose thousands of dollars in federal funding.

''Hundreds of thousands. Police department only,” Healy says. “All of a sudden to be told by the feds you're getting nothing?''

At the same time, Healy wants everyone in Brockton to feel like they can come to him with their problems.

A couple years back, he says, he got to know a group of Brazilian women who worked at a Dunkin' Donuts. He saw their English get better and better. They always had his coffee ready for him when he arrived.

“All of a sudden, one evening, they were all gone,” Healy remembers. “There was talk of a raid coming. They disappeared.”

Those women, they were hiding from him.

“It was kind of heart breaking,” says Healy, “because personally, all I care about is how that coffee’s made.”

Healy says he would never want to get anyone in trouble for their immigration status. That’s a job for immigration officials, not his. He just worries what formalizing that policy could mean.

There is none of this ambivalence at a pizza parlor across town, where members of the Brockton Republican Committee gather.

This is the same night that Lopez and her group hold their meeting in the back of the church.

Here, though, the television is on and the mood is jubilant.

“We were just looking at President Trump on the news talking about defunding sanctuary cities,” says Craig Pina, a real estate agent. “And rightfully so. We can't codify disobeying federal law — then the whole system crumbles.”

Bob Wisgirda, a local radio host, says he opposes the Trust Act because he thinks undocumented immigrants make his city dangerous.

“These are hardened criminals because they are on a daily basis killing people in the city of Brockton,” he says, his voice rising.

Yet decades of research show that immigrants, regardless of their legal status, commit fewer crimes than people born in the US.

But the debate here seems to be less about facts than political views.

“I see it every day, undocumented immigrants driving, causing hit-and-run accidents, some of these things aren’t recorded because you can’t record a hit-and-run accident,” says Pina. “To say they commit less crimes? You realize just being here is a crime.”

However, that assumption is not accurate. Being in the US without proper paperwork is a civil offense, not a crime (and, today, many immigrants out of status in the US have overstayed their visa). However, crossing the border illegally is a federal misdemeanor and punishable by a fine or jail time.

Specifics aside, tension between longtime Brockton residents and some immigrants since the presidential election has been palpable.

“Brockton Interfaith, that’s another problem,” says Pina, when someone mentions the group that's fighting to get the Trust Act passed. “If it's my life mission, it's to destroy that organization.”

As residents wait for city councilors to put the Trust Act to a vote yet again, next month, there's a feeling in the air, kind of like something might snap.

A feeling not so different, maybe, from the national mood.